“There are so many enemies of democracy in Tunisia who want to do everything they can to torpedo the country’s democratic and social life from within,” he said in a meeting with the Washington Post Editorial Board and reporters.

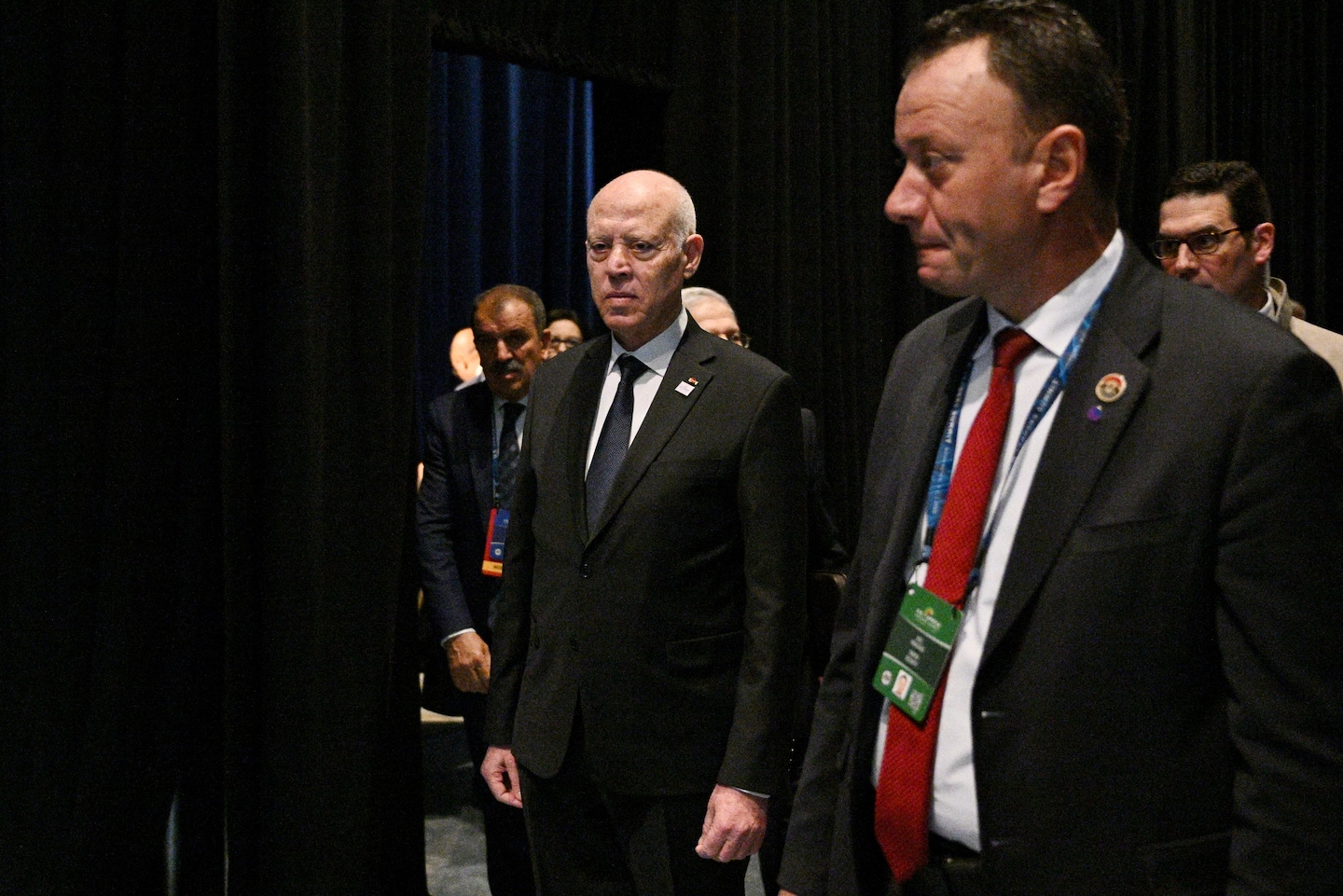

Saied spoke at an important moment for Tunisia, more than a decade after the 2011 uprising that ended a longtime dictatorship and touched off a wave of revolution across the Arab World. His visit to Washington, for President Biden’s Africa summit, occurs just days before an election the Tunisian leader hopes will end a period of friction with a principal backer, the United States.

But clashing U.S. and Tunisian narratives about the events since Saied’s 2019 election — and, crucially, following his 2021 suspension of parliament — appeared to signal during the visit a hardening of the two countries’ standoff, as the Biden administration threatens to withhold needed assistance and Saied rebuffs any hint of reproach.

Washington championed Tunisia’s fledgling democracy following the ouster of autocrat Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, scrambling to provide political and economic support. While other Arab Spring nations descended into conflict, chaos or military rule, Tunisia stood out as bright spot. Now, citing democratic reversal, the Biden administration has slashed civilian and military aid to Tunisia by nearly half in its fiscal 2023 budget.

Sarah Yerkes, a former U.S. official who studies Tunisia at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said Saied’s hopes that the vote set for this weekend, which will elect a legislative body to replace the parliament he suspended, would end strains with Washington were unlikely to bear out. U.S. officials have already complained about steps to weaken legislative powers, alter electoral procedure and overhaul the country’s independent electoral body.

“Saied seems to believe that after the elections on Saturday, things will return to the status quo ante,” she said. “The United States is not likely to let that happen, nor should they.”

Many Tunisians, weary of political deadlock and desperate for jobs and growth, initially supported Saied’s actions. The one-time law professor was elected in 2019 with more than 70 percent of the vote on promises to eradicate corruption and fix the problems that had dogged Tunisia since its heady revolutionary days.

But his support flagged as he has made a series of increasingly authoritarian moves — dissolving the country’s most senior judicial body, firing judges en masse, and introducing a constitution that gives him broad new executive authority — without delivering on the pocketbook problems that seem to worry Tunisians most.

Saeid’s constitution was approved in a July referendum that was marked by low turnout and brought an unusually sharp public rebuke from Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who cited “an alarming erosion of democratic norms over the past year [that] reversed many of the Tunisian people’s hard-won gains since 2011.” Saied’s government shot back, summoning the top U.S. diplomat in Tunisia and decrying “unacceptable foreign interference.”

The government has prosecuted activists and journalists for criticizing authorities, sometimes in military courts, and introduced laws that critics warn are likely to chill freedom of expression. It has also subjected political opponents to trial or travel bans.

Opposition parties, including the Islamist Ennahda party, have labeled Saied’s actions a “coup.” The country’s powerful UGTT trade union recently came out against Saied’s agenda and denounced the upcoming elections.

In his hour-long discussion with The Post, Saied declined to acknowledge any legitimate criticism and outlined a shadowy campaign to undermine his rule.

“It’s a full orchestrated movement that is undertaken by these enemies of democracy who wanted to loot the people, who wanted to rob the people, and who wanted to blow the state up from inside,” he said.

He defended his July 2021 decision to suspend parliament, saying seats were being “bought and sold” in the previous parliament. He said the 2022 constitution provided Tunisians greater rights and protections than the country’s previous constitution. Critics say the charter demolishes checks and balances needed to guarantee such rights and call Saied’s drafting process opaque.

While Biden administration officials say they typically prefer to deliver criticism about partner nations’ records on human and political rights in private, they have taken a sharply critical public stance on Tunisia. It represents a divergence from allies in Europe, who analysts say are more focused on stemming the wave of migrants pouring in from North Africa.

Saied spoke following a meeting with Blinken, who in his opening remarks referenced his hopes for transparent elections.

A senior State Department official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the high-level talks, said that while the Biden administration supported Saturday’s election, it would look for additional steps to put Tunisia on a different course.

“It’s always about more than elections,” the official said. “It’s about implementation; it’s about the democratic spirit that has to transcend the mechanism of elections themselves.”

Even more perilous than foreign critiques for Saied could be the intense economic duress felt by millions of Tunisians, many of whom have risked the perilous journey across the Mediterranean to seek better jobs and pay in Europe.

After contracting by nearly 9 percent at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, Tunisia’s economy now faces inflationary head winds caused in part by Russia’s war in Ukraine. The government is hoping the International Monetary Fund will sign off in coming days on a $2 billion lifeline that could help it avert default.

Asked how he could introduce economic reforms required for the IMF deal without further alienating Tunisians, Saied he would seek to help small businesses and combat unemployment, but provided few details.

“Of course, if we want to successfully implement economic and social reforms, we need a totally neutral and impartial administration,” he said.

Salsabil Chellali, Tunisia director at Human Rights Watch, said Saied had been unable to solve the economic hardship that concerns Tunisians.

“Saied now owns the crisis,” she said. “And it’s up to the Tunisian people, with support from friends of democracy everywhere, to demand a return to accountable government, one with checks and balances and human rights safeguards, as the best way forward.”