|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Christopher Honeyman talks us through recently published work which compared three Marine Protected Area (MPA) monitoring techniques, along with colleagues. Interestingly, each technique was shown to survey distinct groundfish community assemblages with varying levels of species diversity and richness. Therefore, combining multiple techniques may better allow managers to create the most comprehensive, effective and inclusive MPA monitoring regimes.

A global phenomenon

In response to human-caused climate change, overfishing, and a host of other factors, organizations around the world are calling for a global increase in the amount of wild spaces that are protected from extractive human activities. In an effort to address these concerns and protect coastal waters, many countries are looking to expand existing or implement new MPAs. MPAs, designated areas of the ocean where certain human activities – namely fishing – are restricted, are often controversial upon implementation but have been shown to be capable of increasing the number and size of targeted (i.e. ‘fished’) species within their boundaries when properly managed.

As the effects of climate change increasingly threaten coastal communities, many managers are looking beyond replenishing fished stocks and implementing MPAs with the hopes of preserving ecosystem structure, function, and services that offer natural protection from storm surges, sea level rise, and other natural disasters. Because MPA management is a costly endeavour, in both resources and time, resource managers responsible for both new and existing MPAs need to be aware of the most effective strategies to ensure success.

Long-term monitoring and resource management

Long-term monitoring, when done correctly, provides data on whether or not species and ecosystems are responding to protection, making it a critical component of effective management. Because many managers implement MPAs with specific conservation goals in mind, it is imperative that monitoring programs are capable of addressing these concerns.

While a host of viable methods exist to monitor marine communities, the questions managers have may range from the species-specific to the ecosystem level, with each requiring a different technique to effectively answer. With so many monitoring methods to choose from, how are resource managers supposed to know which method (or methods) are most relevant for their study system?

Scuba diving, collaborative fishing, and baited cameras, oh my!

In order to provide actionable advice to managers unsure of which monitoring method to use, we compared data from three existing MPA monitoring programs used by the state of California, USA, to monitor fish populations across its MPA network, one of the largest in the world.

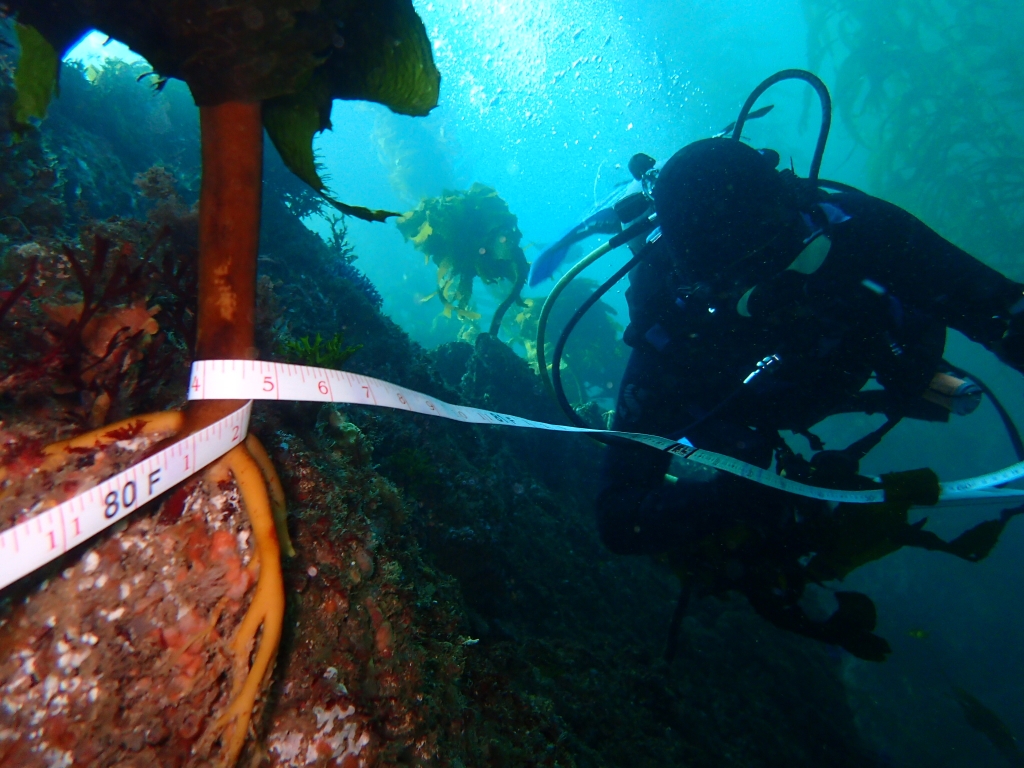

Each method (visual surveys done on SCUBA (UVC), collaborative catch-and-release fisheries surveys (CCFRP), and baited remote underwater videos (BRUVs)) is frequently used around the world and has been a central component of California’s ongoing management strategy. There are multiple locations across California’s MPA network where all three of these methods are conducted, offering the perfect opportunity for comparative analysis.

The big picture

In a new article recently published in the Journal of Applied Ecology, we analysed results from the aforementioned methods (UVC, CCFRP, and BRUVs), looking for similarities across three common metrics of MPA assessments: fish abundance, biomass, and community structure.

While we found each monitoring method generally detected both more and bigger fish from targeted species inside MPAs, individual species’ responses varied across tools and locations. Additionally, each method was shown to capture a distinct groundfish community structure and differing levels of species diversity, an interesting result considering each tool surveyed the same reefs in multiple instances.

Management implications

Our results indicate there is likely no “one-size-fits-all” approach to comprehensive MPA monitoring. While each of our tools provided the same “bird’s eye view” of MPA performance, species-specific responses conflicted for a variety of commercially and recreationally important species. MPA managers need to be wary and account for both species-specific biology and sampling bias when designing an MPA management routine, especially if an MPA is implemented with the goal of preserving ecosystem function. This will ensure the data collected by monitoring programs will effectively address MPA performance in relation to any conservation goals managers may have.

While one tool alone may answer a subset of questions, the most comprehensive, adaptable, and effective MPA management regimes will utilize a suite of complementary monitoring methods. If managers are resource, time, or personnel limited, great care should be taken to ensure the best method for their particular system is chosen. Only by utilizing multiple tools will resource managers be able to address the weaknesses of one tool with the strengths of another, resulting in greater confidence when measuring MPA responses.

Read the full article “Correspondence among multiple methods provides confidence when measuring marine protected area effects for species and assemblages” in Journal of Applied Ecology