|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Lead author Caitlin Mandeville recalls how she and her co-authors kept their focus close to home in their latest research that explores connections between citizen science and recreation in natural areas.

Just about every community has some small, unassuming natural areas that are mainly known to locals: a neighbourhood park, a small wildlife preserve, a field on the edge of town. These places might not show up in guidebooks or draw tourists, but they tend to be visited regularly and are deeply loved by the people who live near them.

Here in Trondheim, Norway, one of the most treasured places to get out into nature is called Bymarka. A small stretch of forest, lakes and bogs perched on the hills at the edge of town, Bymarka has been at the cultural heart of Trondheim for centuries.

Not only do local natural areas like Bymarka help people connect with nature during day-to-day life, evidence suggests that they’re good for conservation too. They are home to diverse species, bridge gaps between larger areas, and more.

But many small natural areas have limited funding for the active management and monitoring that are needed to maintain healthy ecosystems. In particular, biodiversity monitoring is essential but can be expensive.

The popularity of small natural areas hints at one solution: in addition to hiking, picnicking and other recreational activities, many natural area visitors also like to use citizen science apps that record biodiversity data (e.g. iNaturalist, eBird, and many others!). This is clearly true in Bymarka, where over 85% of terrestrial biodiversity data shared on GBIF in the last 20 years were collected on Norway’s favourite citizen science app.

But putting citizen science data to use can be easier said than done. Citizen science offers both an opportunity (lots of data!) and a challenge (we don’t have a lot of background information on the data). The more we know about any patterns in when, where and how participants report data, the more easily we can use the data for analysis.

We already know that, unsurprisingly, people mostly do citizen science where they live, work and play, especially if they are interested in the nature there. This is why small natural areas with regular visitors are hotspots for citizen science.

But what about within these citizen science hotspots? Once people get to their favourite nature spot, how do they choose where to stop and collect data, and where to keep on walking?

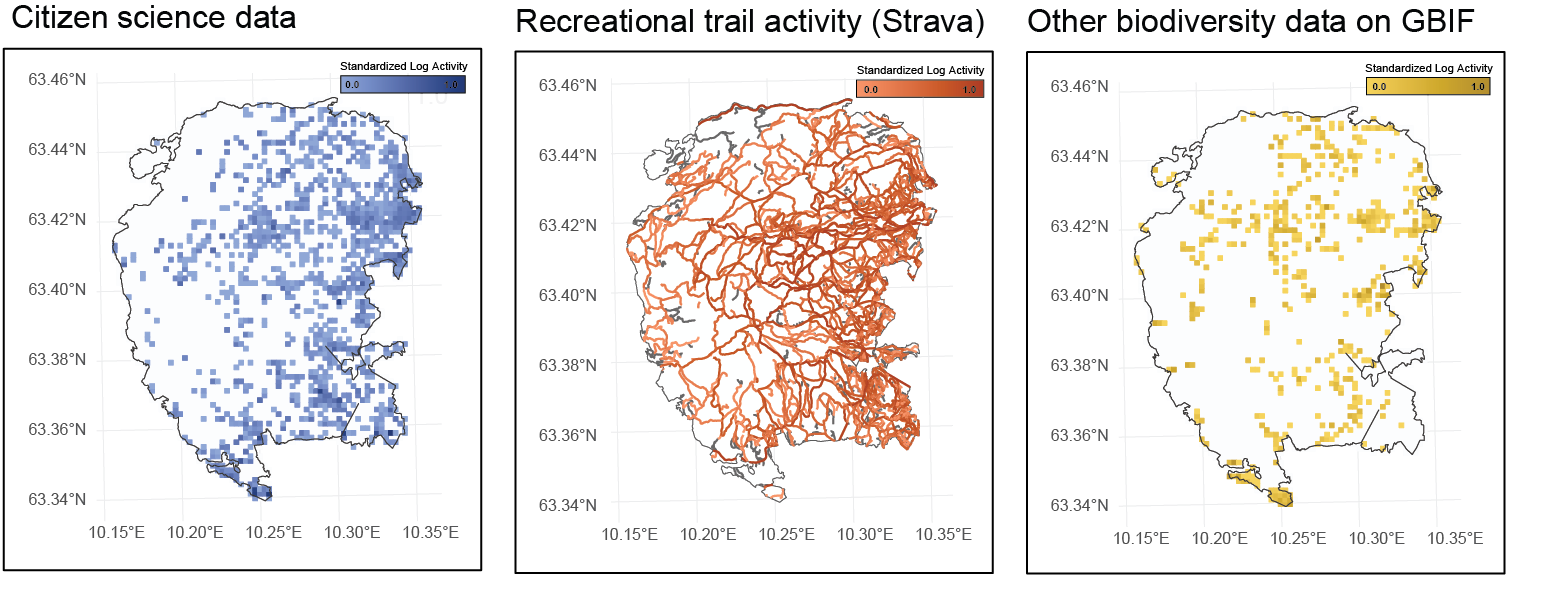

Along with my PhD advisors, I decided to use our own local natural area, Bymarka, to think about these questions. First, we compared the locations of citizen science activity with other recreational trail use reported by users of the Strava activity tracking app. After that, we used modelling to identify common features (such as trail access and habitat types) of the most popular citizen science spots in Bymarka.

To our surprise, we found that citizen science participants used Bymarka’s trails differently than other trail users.

Most visitors to Bymarka spent more time on well-established trails but citizen science participants spread out along trails, ranging from paved paths to muddy tracks. Most visitors didn’t spend as much time around human-built structures or grazing areas but citizen science was as popular in these areas as in more seemingly “natural” spots.

The biggest pattern in citizen science activity was determined by how easily people could access a location – trailheads and parking lots are well-represented in the data. Lakeshores were also popular spots for citizen science (this is true in urban areas, too!). Knowledge of these trends could make it easier to interpret citizen science data from small natural areas.

Above all, it’s inspiring to see how much knowledge citizen scientists produce! Citizen science participants in Bymarka collect data in all kinds of habitats all through the year, reporting over 1500 species so far. We encourage managers of natural areas to see citizen scientists as partners for data collection. Past experience even shows that citizen scientists are often happy to pursue specific data collection goals if asked, making data even more useful.

Maybe you’d like to join me in taking along a citizen science app next time you visit your own favourite local nature spot?

Read the full article, “Spatial distribution of biodiversity citizen science in a natural area depends on area accessibility and differs from other recreational area use”, in Issue 3:4 of Ecological Solutions and Evidence.