(Beirut) – A Saudi court has sentenced a man to death based solely on his X, formally known as Twitter, and YouTube activity, Human Rights Watch said today. Saudi authorities should quash the verdict, which is an escalation of the Saudi government’s crackdown on freedom of expression and peaceful political dissent in the country.

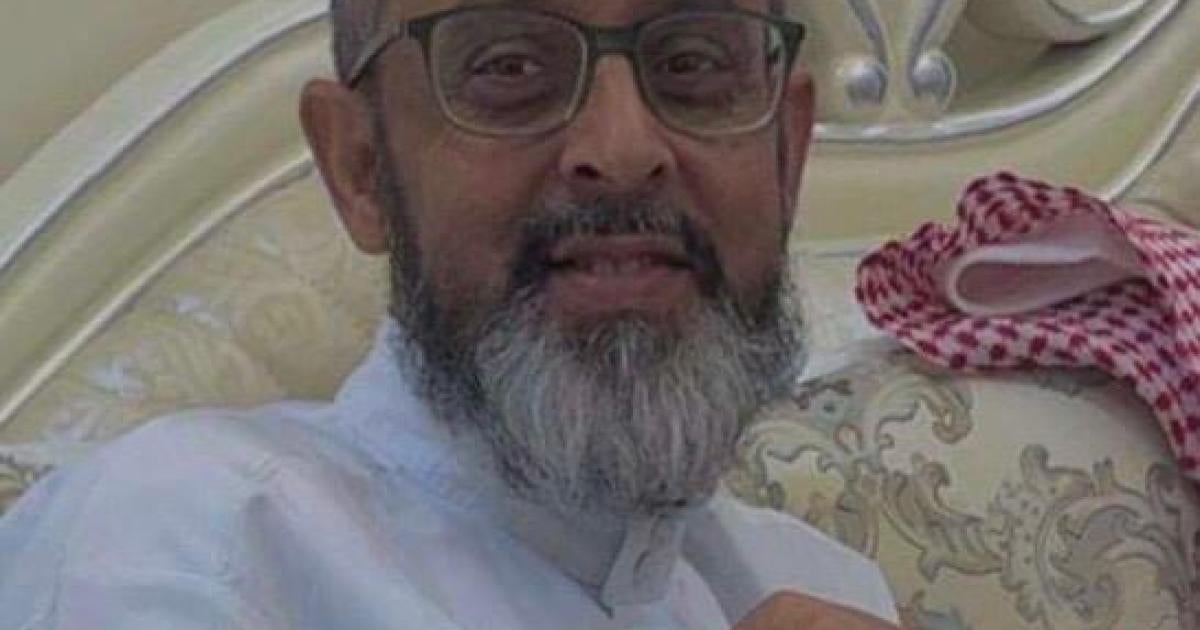

On July 10, 2023, the Specialized Criminal Court, Saudi Arabia’s counterterrorism tribunal, convicted Muhammad al-Ghamdi, 54, a retired Saudi teacher, of several criminal offenses related solely to his peaceful expression online. The court sentenced him to death, using his tweets, retweets, and YouTube activity as the evidence against him.

“Repression in Saudi Arabia has reached a terrifying new stage when a court can hand down the death penalty for nothing more than peaceful tweets,” said Joey Shea, Saudi Arabia researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Saudi authorities have escalated their campaign against all dissent to mind-boggling levels and should reject this travesty of justice.”

Saudi security forces arrested al-Ghamdi in front of his wife and children on June 11, 2022, outside his home in the al-Nouriyyah neighborhood of Mecca, people with knowledge of the case told Human Rights Watch. They took him to al-Dhahban Prison, north of Jeddah, where he was held in solitary confinement for four months. His family was unable to contact him during this period and he did not have access to a lawyer. The authorities later transferred al-Ghamdi to the al-Ha’ir Prison in Riyadh.

Saudi interrogators questioned him about tweets and political opinions and asked his opinions about individuals imprisoned for exercising their right to free expression. Al-Ghamdi did not have a lawyer for nearly a year and once he finally did obtain legal representation, he was only able to speak with the lawyer immediately in advance of court sessions.

Al-Ghamdi’s brother, Saeed bin Nasser al-Ghamdi, is a well-known Saudi Islamic scholar and government critic living in exile in the United Kingdom. In a tweet on August 24, Saeed wrote that the “false ruling aims to spite me personally after failed attempts by the investigations to return me to the country.” Saudi authorities in recent years have increasingly retaliated against the family members of critics and dissidents abroad in an effort to coerce them to return to the country, Human Rights Watch said.

Court documents Human Rights Watch reviewed show that the Specialized Criminal Court sentenced al-Ghamdi to death on July 10 under article 30 of Saudi Arabia’s counterterrorism law for “describing the King or the Crown Prince in a way that undermines religion or justice,” article 34 for “supporting a terrorist ideology,” article 43 for “communication with a terrorist entity,” and article 44 for publishing false news “with the intention of executing a terrorist crime.” Al-Ghamdi’s trial judgment states that he used his accounts on the X platform and YouTube to commit his “crimes.”

The public prosecutor sought the maximum penalties for all charges against al-Ghamdi. The documents say that the court issued the sentence on the grounds that the crimes “targeted the status of the King and the Crown Prince,” and that the “magnitude of his actions is amplified by the fact they occurred through a global media platform, necessitating a strict punishment.”

The documents cite two X platform accounts as belonging to al-Ghamdi. Human Rights Watch found that the first account had two followers and the second had eight. Both accounts, which have fewer than 1,000 tweets combined, largely contained retweets of well-known critics of the Saudi government.

The charging document cites as evidence several tweets criticizing the Saudi royal family, and at least one calling for the release of Salman al-Awda, a prominent cleric facing a possible death sentence on various vague charges related to his political statements, associations, and positions, and of other prominent imprisoned Islamic scholars.

Al-Ghamdi does not consider himself a political or human rights activist, said those with knowledge of the case. He maintains that he is a private citizen who merely expressed some concerns about the Saudi government over the X platform, they said.

Al-Ghamdi suffers from a number of serious mental health issues, the sources said, and Saudi authorities have refused to provide him with some of his prescription medications, which are necessary to treat and manage his conditions. Al-Ghamdi’s mental and physical health have greatly deteriorated since his arrest, they said.

Al-Ghamdi’s death sentence is the latest and most severe in a series of cases in which Saudi authorities have targeted social media users for peaceful expression online. Over the past year, Saudi courts have convicted and imposed decades-long sentences on social media users who criticized the government.

In August 2022, a Saudi appeals court dramatically increased the prison sentence of a Saudi doctoral student, Salma al Shehab from 6 to 34 years, based solely on her activity on the X platform. The sentence was later reduced on appeal to 27 years. That same day, a court sentenced another woman, Nourah bin Saeed al-Qahtani, to 45 years in prison for “using the internet to tear the [country’s] social fabric.”

Saudi authorities executed 81 men on March 12, 2022, the country’s largest mass execution in years, despite the leadership’s promises to curtail the use of the death penalty. Saudi activists told Human Rights Watch that 41 of the men belonged to the country’s Shia Muslim minority, who have long suffered systemic discrimination by the government. Human Rights Watch has documented rampant and systematic abuses in Saudi Arabia’s criminal justice system that make it nearly impossible for defendants, including al-Ghamdi, to receive a fair trial.

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly criticized rampant abuses in Saudi Arabia’s criminal justice system, including long periods of detention without charge or trial, denial of legal assistance, and the courts’ reliance on torture-tainted confessions as the sole basis of conviction. The violations of defendants’ rights are so fundamental and systemic that it is hard to reconcile Saudi Arabia’s criminal justice system with a system based on the basic principles of the rule of law and international human rights standards.

International human rights standards, including the Arab Charter on Human Rights, ratified by Saudi Arabia, obligate countries that use the death penalty to use it only for the “most serious crimes,” and in exceptional circumstances. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights released a statement in November 2022 on the alarming rate of executions in Saudi Arabia after it ended a 21-month unofficial moratorium on the use of the death penalty for drug-related offenses.

Human Rights Watch opposes the death penalty in all countries and under all circumstances. Capital punishment is unique in its cruelty and finality, and it is inevitably and universally plagued with arbitrariness, prejudice, and error.

“Saudi authorities are now resorting to online criticism not only with unfair show trials, but with the threat of capital punishment,” Shea said. “It’s difficult to see how the Saudi leadership’s pledges to become a more rights-respecting society are meaningful when a mere critical tweet can lead to a death sentence.”