Dr. Muscarella, a pipe-smoking, Sherlock Holmes-quoting rabble-rouser, didn’t care about angering his superiors, who unsuccessfully tried to fire him three times and disrupt what became a four-decade quest to prove that many antiquities held by the Met and other museums were stolen or fake.

“This museum is one of the main plunderers in this planet’s history, and it will not stop it,” Dr. Muscarella, who died Nov. 27 at age 91, told Newsday in 1995. “There are things in this museum that are plundered. It didn’t fall from the sky.”

After joining the Met in 1964, Dr. Muscarella spent years battling museum officials, including the powerful director Thomas Hoving, over labor issues and pushback from his criticism. But after a court-ordered fact-finder in 1977 ultimately sided with Dr. Muscarella, declaring that he had not displayed “unprofessional and improper conduct,” the Met had no choice but to keep him on staff.

It was an uncomfortable arrangement.

“I don’t think I’ve ever spoken to Oscar Muscarella,” Harold Holzer, then the Met’s communications director, told the Village Voice. “I just don’t understand why anyone who hates museums would work in a museum.”

But Dr. Muscarella didn’t hate museums. He deplored what he called “bazaar archaeology” — the community of morally corrupt museum curators, collectors and dealers who looked the other way as they traded, sold and displayed looted or fraudulent artifacts. The only artifacts that museums should hold and display, he thought, were those collected and properly documented by archaeologists.

“I am against all buying of ancient art from dealers,” Dr. Muscarella told the New York Times in 1978. “If the objects are genuine, we’re buying plundered art; if they are false, we’re buying forgeries. And the public is paying for these forgeries or for these bribes to looters and public officials.”

Dr. Muscarella first became critical of the Met’s antiquities dealings in 1973 after the museum’s purchase — for approximately $1 million — of a 2,500-year-old Greek vase from Robert E. Hecht Jr., a controversial dealer who was later indicted in Italy on charges that he dealt in looted artifacts. The statute of limitations expired before the trial ended.

As museum visitors lined up to view the vase, questions surfaced about its price and provenance. Dr. Muscarella worried that the piece had been looted and that its extraordinarily high price — curators at other museums appraised the vase at $500,000 or less — would encourage similar behavior by shady dealers.

Met officials brushed off the questions.

“Why can’t we just appreciate the vase for what it is: a glorious object with brilliant colors and an extraordinary composition?” Dietrich von Bothmer, then the museum’s curator of Greek and Roman art, told the New York Times.

Dr. Muscarella disagreed, telling the paper that his bosses had “abdicated responsibility” and that they “should have checked out every possible origin, of our vase before it was purchased.”

He was right. Italian government officials said the vase had been looted from the country’s soil, and they waged a three-decade battle to get it back. The Met finally returned it in 2008.

Though he was ostracized by many of his peers at the Met, Dr. Muscarella persisted in what became a lifelong quest to expose other looted or fraudulent artifacts. Speaking at conferences and in media interviews, he frequently quoted his hero, Sherlock Holmes. One of his favorites was: “I never guess; it is a shocking habit — destructive to the logical faculty.”

In 1978, he published a study alleging that 247 ancient Near Eastern artifacts held in museums or displayed in collection catalogues were of suspicious origin or frauds. Two years later, at a lecture at the University of Chicago, Dr. Muscarella said none of them had been removed.

“Some say a public debate is not the ‘gentlemanly’ way of doing things,” Dr. Muscarella told his audience. “I don’t expect anyone to take my word as gospel, but any museum director who refuses to have a suspect object tested should be fired — it’s a betrayal of everything he stands for. Such attitudes amount to a corruption and destruction of the discipline, and make the director an accomplice to a distortion of the past.”

Dr. Muscarella kept digging.

In 2000, he published “The Lie Became Great: The Forgery of Ancient Near Eastern Cultures,” in which he catalogued more than 1,250 suspicious artifacts around the world. “If collecting stopped,” he wrote in the book’s introduction, “plunder would stop — certainly it would be mitigated — and forgery manufacturing would decrease. But these arguments are derided as naive by the self-serving and partisan collecting culture, which is essentially a component of the forgery culture.”

Oscar White was born March 26, 1931, in Manhattan. His father, an elevator operator, and his mother weren’t married. As a toddler, his mother abandoned him and his brother, who lived in foster care until 1937 when they were reunited. By then, she was in a relationship with another man — Salvatore Muscarella, marrying him in 1939.

Oscar excelled in school. He was admitted to Stuyvesant High School, a public but competitive college-preparatory school in Manhattan, where he joined the archaeology club. After graduating in 1948, he briefly studied at New York University but dropped out and enrolled at City College, where he studied in history. In 1953, he saw a campus announcement for an upcoming archaeological dig at a Pueblo Indian site in Colorado and traveled there by bus to work.

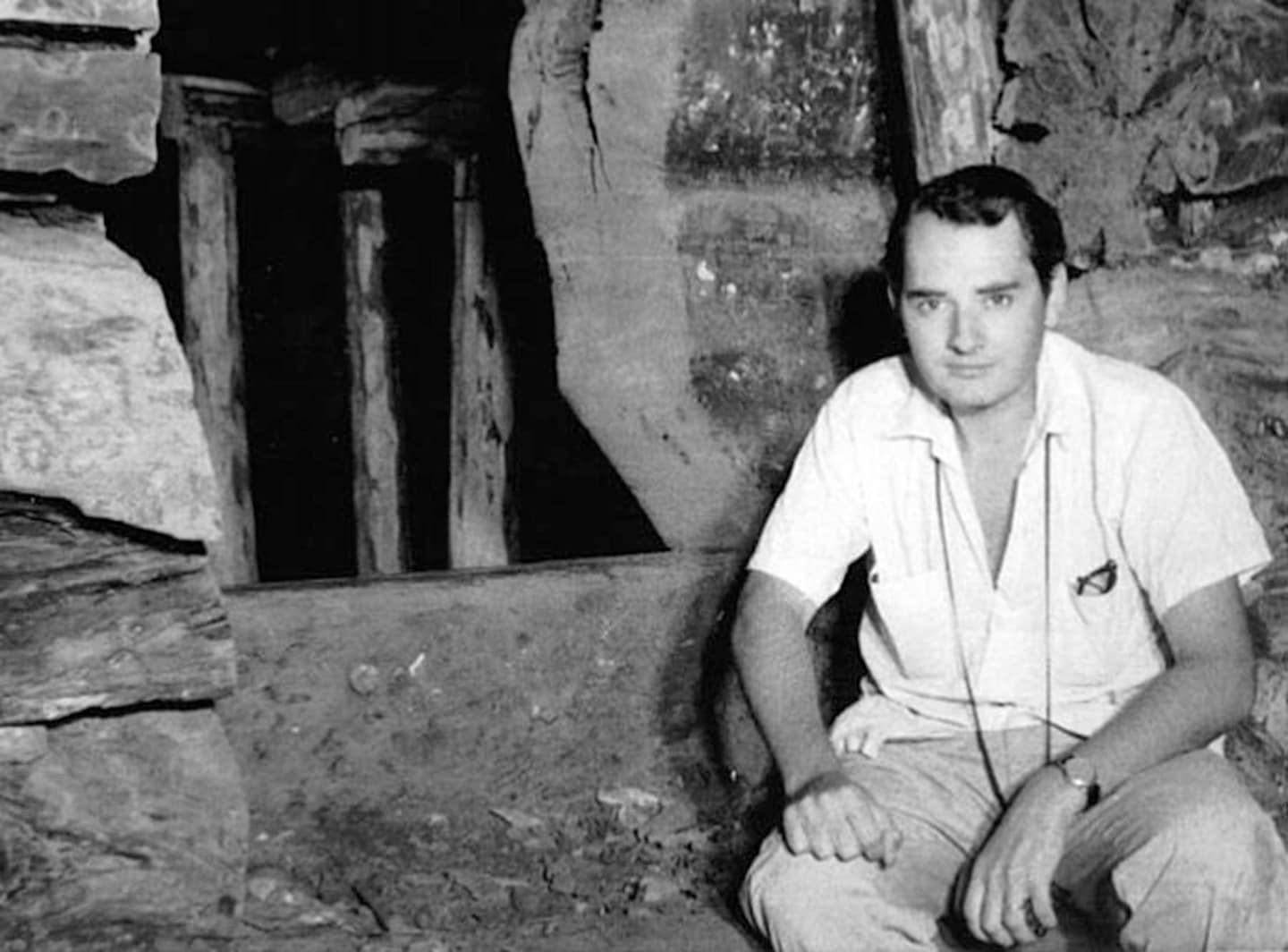

After graduating from City College in 1955, he earned a doctorate in classical archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania, where he met fellow graduate student Grace Freed, marrying her in 1957. Dr. Muscarella worked at dozens of archaeological sites around the world.

“His work spans an area from Greece to Afghanistan, from the Neolithic to the Persian period,” Elizabeth Simpson, an archaeologist and historian, wrote in the introduction of an essay collection about his work. “Oscar has persisted against formidable odds to become one of the profession’s outstanding archaeologists, in the broadest sense of the term.”

Dr. Muscarella died at home in Philadelphia, his son Lawrence F. Muscarella said. The cause was lymphoma, though Dr. Muscarella had also been ill with cerebral vascular disease and covid-19.

In addition to his son, he is survived by his wife; a daughter, Daphne M. Dennis of North Wales, Pa.; and a granddaughter.

Despite the antagonism between Dr. Muscarella and his bosses, he remained employed by the Met until his retirement in 2009.

“He was largely excluded from departmental matters,” Simpson wrote. “He often was not told about acquisitions, gallery changes, meetings, newly appointed staff, or visiting colleagues.”

Still, Dr. Muscarella carried on with his work.

“As anyone who knows him can attest,” Simpson wrote, “and as his life story shows, Oscar is not to be deterred.”