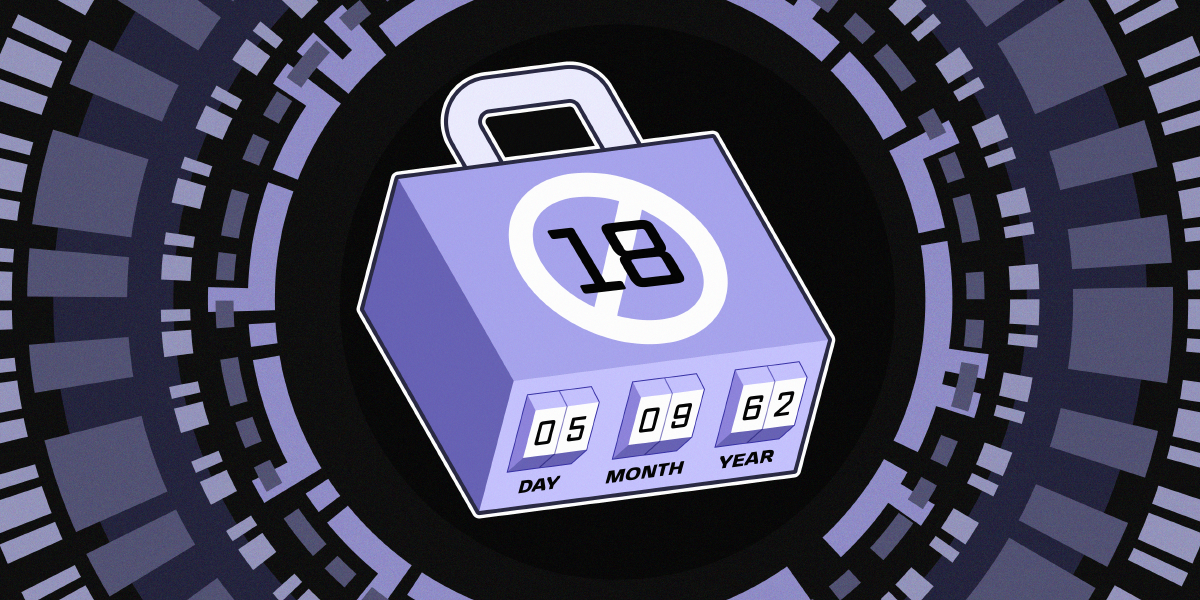

Young people should be able to access information, speak to each other and to the world, play games, and express themselves online without the government making decisions about what speech is permissible. But in one of the latest misguided attempts to protect children online, internet users of all ages in the UK are being forced to prove their age before they can access millions of websites under the country’s Online Safety Act (OSA).

The legislation attempts to make the UK the “the safest place” in the world to be online by placing a duty of care on online platforms to protect their users from harmful content. It mandates that any site accessible in the UK—including social media, search engines, music sites, and adult content providers—enforce age checks to prevent children from seeing harmful content. This is defined in three categories, and failure to comply could result in fines of up to 10% of global revenue or courts blocking services:

- Primary priority content that is harmful to children:

- Pornographic content.

- Content which encourages, promotes or provides instructions for:

- suicide;

- self-harm; or

- an eating disorder or behaviours associated with an eating disorder.

- Priority content that is harmful to children:

- Content that is abusive on the basis of race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, disability or gender reassignment;

- Content that incites hatred against people on the basis of race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, disability or gender reassignment;

- Content that encourages, promotes or provides instructions for serious violence against a person;

- Bullying content;

- Content which depicts serious violence against or graphicly depicts serious injury to a person or animal (whether real or fictional);

- Content that encourages, promotes or provides instructions for stunts and challenges that are highly likely to result in serious injury; and

- Content that encourages the self-administration of harmful substances.

- Non-designated content that is harmful to children (NDC):

- Content is NDC if it presents a material risk of significant harm to an appreciable number of children in the UK, provided that the risk of harm does not flow from any of the following:

- the content’s potential financial impact;

- the safety or quality of goods featured in the content; or

- the way in which a service featured in the content may be performed.

- Content is NDC if it presents a material risk of significant harm to an appreciable number of children in the UK, provided that the risk of harm does not flow from any of the following:

Online service providers must make a judgement about whether the content they host is harmful to children, and if so, address the risk by implementing a number of measures, which includes, but is not limited to:

- Robust age checks: Services must use “highly effective age assurance to protect children from this content. If services have minimum age requirements and are not using highly effective age assurance to prevent children under that age using the service, they should assume that younger children are on their service and take appropriate steps to protect them from harm.”

To do this, all users on sites that host this content must verify their age,

for example by uploading a form of ID like a passport, taking a face selfie or video to facilitate age assurance through third-party services, or giving permission for the age-check service to access information from your bank about whether you are over 18. - Safer algorithms: Services “will be expected to configure their algorithms to ensure children are not presented with the most harmful content and take appropriate action to protect them from other harmful content.”

- Effective moderation: All services “must have content moderation systems in place to take swift action against content harmful to children when they become aware of it.”

Since these measures took effect in late July, social media platforms Reddit, Bluesky, Discord, and X all introduced age checks to block children from seeing harmful content on their sites. Porn websites like Pornhub and YouPorn implemented age assurance checks on their sites, now asking users to either upload government-issued ID, provide an email address for technology to analyze other online services where it has been used, or submit their information to a third-party vendor for age verification. Sites like Spotify are also requiring users to submit face scans to third-party digital identity company Yoti to access content labelled 18+. Ofcom, which oversees implementation of the OSA, went further by sending letters to try to enforce the UK legislation on U.S.-based companies such as the right-wing platform Gab.

The UK Must Do Better

The UK is not alone in pursuing such a misguided approach to protect children online: the U.S. Supreme Court recently paved the way for states to require websites to check the ages of users before allowing them access to graphic sexual materials; courts in France last week ruled that porn websites can check users’ ages; the European Commission is pushing forward with plans to test its age-verification app; and Australia’s ban on youth under the age of 16 accessing social media is likely to be implemented in December.

But the UK’s scramble to find an effective age verification method shows us that there isn’t one, and it’s high time for politicians to take that seriously. The Online Safety Act is a threat to the privacy of users, restricts free expression by arbitrating speech online, exposes users to algorithmic discrimination through face checks, and leaves millions of people without a personal device or form of ID excluded from accessing the internet.

And, to top it all off, UK internet users are sending a very clear message that they do not want anything to do with this censorship regime. Just days after age checks came into effect, VPN apps became the most downloaded on Apple’s App Store in the UK, and a petition calling for the repeal of the Online Safety Act recently hit more than 400,000 signatures.

The internet must remain a place where all voices can be heard, free from discrimination or censorship by government agencies. If the UK really wants to achieve its goal of being the safest place in the world to go online, it must lead the way in introducing policies that actually protect all users—including children—rather than pushing the enforcement of legislation that harms the very people it was meant to protect.