|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Wim De Schuyter, Pieter De Frenne, Emiel De Lombaerde, Leen Depauw, Pallieter De Smedt, Lander Baeten, Kris Verheyen explore declining potential nectar production in this post and also at: https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1365-2745.14274

Springtime is upon us and soon new generations of insects will emerge and buzz around in our landscapes. In search for food, and later on nesting materials or mating partners, they will bring back life in our gardens, parks, fields and forests after a cold and dark winter period. In doing so, they will pollinate countless flowers and help produce fruits, vegetables and the next year’s flowering plants that add colour to our daily life.

This is how it always has been and will be for a long time to come. Or do we have to worry about our beloved aerial dancers? Scientific evidence convincingly shows that wild pollinator communities are in severe decline across the globe. Mainly due to habitat loss and degradation, pesticides and climate change. European literature mostly focusses on the dynamics in well-known habitats for wild pollinators like species-rich grasslands, road verges or hedgerows. However, the contribution of forests, which are heavily affected by climate change, as potential habitat for pollinators has been understudied to date. In our new study in Journal of Ecology, we look deeper into this relationship between forests and wild pollinators.

Clearly, the dancers’ symphony has hit sour notes in past decades and with our study we strive to contribute in preventing pollinators completely losing sync.

What did we compose?

We delved into a particular part of the complex symphony, which the relation between forests and pollinators is, and assessed the forest herb layer (<1m) as a potential interesting source of nectar for wild pollinators.

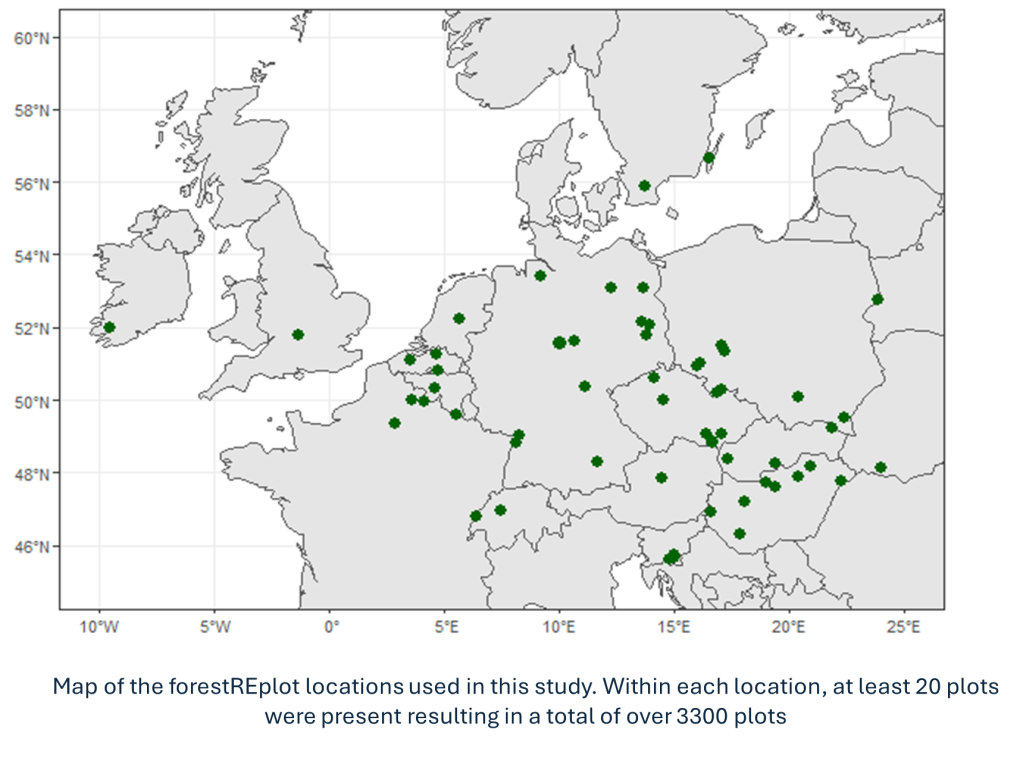

Firstly, we looked at present-day herb layer communities and how the nectar availability they provide varies throughout the year. Then, we quantified how nectar availability has changed over decades. Finally, we combined the two patterns, and looked at how the availability throughout the year has changed over decades. Our work used vegetation resurvey studies. These are studies where herb layer vegetation cover was recorded for at least two points in time at (more or less) the exact same location. We used data from the forestREplot database, covering over 3300 of such resurvey plots. To this database, we added data on nectar production for each plant species, resulting in the first quantification of nectar availability in the forest herb layer. Important to note here is that we estimated the potential nectar production per plot rather than measure the actual nectar production, for instance because we had no data on how many of the plants present were actually flowering.

What melody did it echo?

The forest herb layer has a large potential for providing resources for wild pollinators comparable to literature values obtained for species-rich grasslands. Throughout the year, we found that the bulk of nectar production occurs in spring before the canopy of the forests closes. This is coherent with findings in other habitat types, but remarkable is that the peak of nectar production in forests occurs earlier in spring than observed in those other land-uses. This is, for example, particularly interesting for early emerging bumblebee queens.

Our results also underpin that this potential nectar production has drastically decreased over time, with an average decline of almost 25%. The important drivers behind this decline were mostly related to the forest management. The studied forests have – on average – become denser and shadier over the last decades and this has led to a reduced cover of high nectar-producing plant species. Over the years, nectar availability in both spring and summer has decreased. Spring nectar production occurs on a narrower time frame and summer nectar production has almost faded.

What does the music tell us?

European forests should definitely not be overlooked as habitat for wild pollinators. The forest herb layer alone has a large potential for providing nectar and if we hereby add resources (nectar, but also pollen and nesting materials) provided by trees and shrubs, forests undoubtedly play a big role for pollinators. Future research into the actual resources provided by forests is key to completely comprehend the complex forest-pollinator symphony. Studies into actual measurements of nectar and pollen provision by different kinds of forests or the actual resource contribution of trees and shrubs for pollinators would greatly improve our understanding of the role of forests in providing pollination services.

Forests are under threat globally and have changed over the past decades. In many European forests, there has been an increase in tree species appealing to pollinators, such as maple species, which would be beneficial for pollinators. This trend is opposite to what we observed for the forest herb layer that exhibits a decreased attractiveness for pollinators. Future research will have to bring clarity into what effects – positive or negative – the pollinator communities ultimately perceive.

The studied forests have become darker and shadier as a consequence of less intense management. Forest densification is beneficial for both microclimate buffering and many specialist forest plants. In order to sustain those benefits, while also enhancing nectar production at the forest floor, we would argue for more and larger forests, which give the opportunity to opt for a diversity of management approaches creating a pattern between darker, colder spots and lighter, hotter spots. Thereby, both creating attractive pollinator zones and maintaining zones with cool, well-buffered microclimates.

Read the team’s paper: Declining potential nectar production of the herb layer in temperate forests under global change here: https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1365-2745.14274

Wim De Schuyter, Pieter De Frenne, Emiel De Lombaerde, Leen Depauw, Pallieter De Smedt, Lander Baeten and Kris Verheyen are from Forest and Nature Lab, Department of Environment, Ghent University, Geraardsbergsesteenweg 267, 9090 Melle, Belgium

Follow them on X: @ForNaLab @GhentUniversity

Also: ForNaLab: https://www.ugent.be/bw/environment/en/research/fornalab

forestREplot: https://forestreplot.ugent.be/

researchgate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Wim-De-Schuyter

OCRID: https://orcid.org/my-orcid?orcid=0000-0003-4280-1263