“I am mad for it to be in contact with me,” Walt Whitman wrote, of what he called “life’s atmosphere.” No doubt he also meant contact with the bodies of the many people he cruised and desired. Likewise, Twitter seems to offer contact with everyone, and the interface exists to make users mad for contact as it conjures life’s atmosphere of abrasiveness streaked with sweetness. The real Twitter was the friends we made along the way, as someone has surely tweeted.

That’s gone now. When the chief rolls in with tryhard trolling that misses the mark of humor, squealing in annoying feedback loops from his Wall of Sound, the warm chatter among the regulars goes silent. A pall falls. When Musk tweeted some horror fiction alleging that the spouse of a prominent elected official might have been perversely complicit in cracking his own skull with a hammer, something at the heart of Twitter seemed to die. Later, when he bellowed that Twitter in 2020 had abridged the constitutional right of trolls to post a Hunter Biden dick pic, another influx of refugees poured into Mastodon, which presents itself as a more normal haven for people fleeing Twitter.

“The Internet Is for Porn” was the catchiest song from Avenue Q, which debuted 20 years ago. That was before broadband, before social media, before the hijack of information space by influence operations and strongman solo acts like GOP trinity Kanye, Elon, and Trump. It was axiomatic back then. Porn was the internet’s reason for being, its prime directive. And it would have stayed that way had web information not been domesticated by corporations that wanted to hack our worldviews and pick our pockets for data, attention, and mobile payments.

But through all this, Twitter has retained the spirit of porn. Like porn, Twitter is not a family affair; for many, it’s also a shameful habit that they’re forever trying to quit. Since 2007, I’ve turned to Twitter to—the only word I can think of is learn. But I know its traps well. Users of Twitter, like consumers of porn, find themselves amused and stimulated, and then scroll compulsively, chasing the dragon of human connection, only to find themselves scrolling through doom, and finally scrolling for doom.

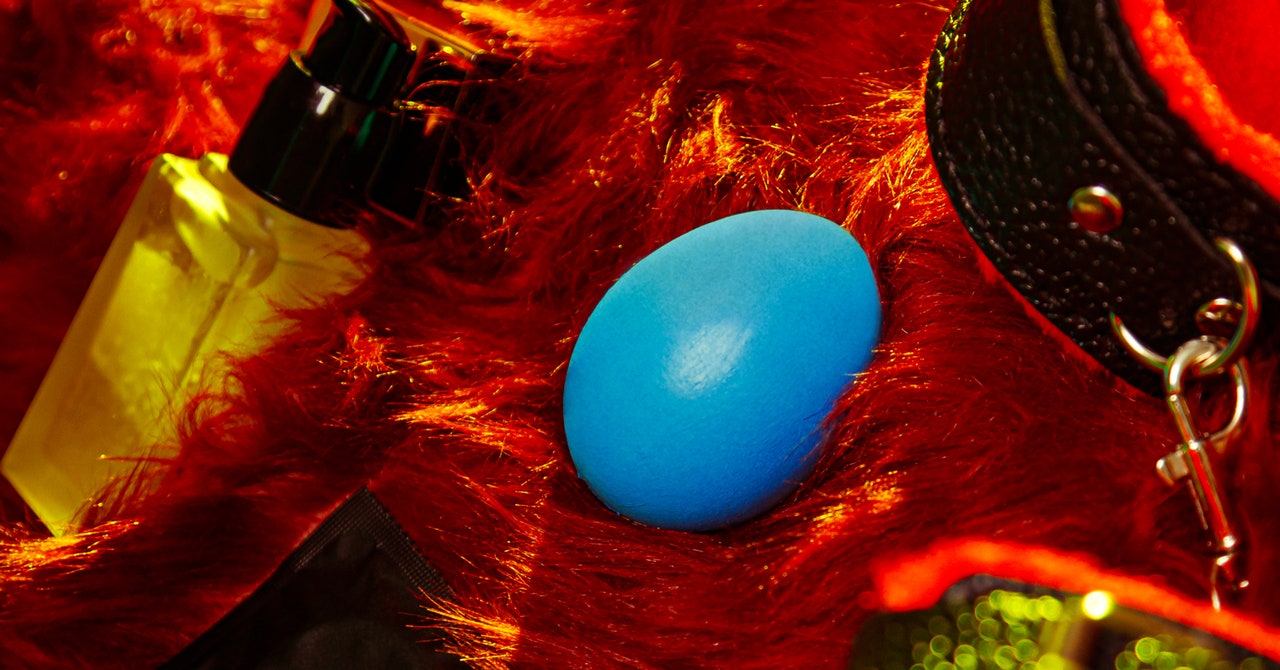

Information may or may not want to be free, but it often wants to be porn. What Musk has considered doing, according to various reports, is introduce paywalled video that would allow performers to get paid while Twitter takes a cut. Sound at all familiar? It’s the OnlyFans model, complete with a rip-off of the OnlyFans interface. The performers it’s tailor-made for are not, as it happens, cellists or mimes. They’re sex workers. And for discerning high rollers who prefer the backroom to the club, Musk has floated the idea of offering paid DMs—to be slipped into as usual, but for a fee. The online-porn business demands extreme discipline to keep it from turning criminal and leaves room for little else, but edgelord Musk is likely to fare better in the demimonde than he is on the main stage.

At the very end of 2022, NSFW content was the fastest-growing sector of English-language Twitter. It’s the way of the world, especially without diligent moderation. At the same time, the new louche Twitter comes with a harum-scarum idea of “free speech” as singularly applicable to obscene provocateurs like Jordan Peterson and Marjorie Taylor Greene, formerly banned figures who were warmly welcomed back to the site in November. “This is a battle for the future of civilization,” the Chief Twit tweeted. “If free speech is lost even in America, tyranny is all that lies ahead.”

If Twitter is going to prey on users with hyper-arousing material and the illusion of intimacy, why not go all the way? Twitter should admit what it’s up to, tell risk-averse advertisers to go blow if they’re prudes, and turn full red-light district. It might scare away the squares, but Twitter can charge a mint for spank-bank material, and a premium for the kind that somehow prevents tyranny.

This article appears in the February issue. Subscribe now.

Let us know what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor at [email protected].