Cathryn Grothe, a research analyst at Freedom House, a US government–backed nonprofit that works on human rights, says she has seen a shift in Iran in recent years away from a reliance on informants and physical patrols toward forms of automated digital surveillance to target critics.

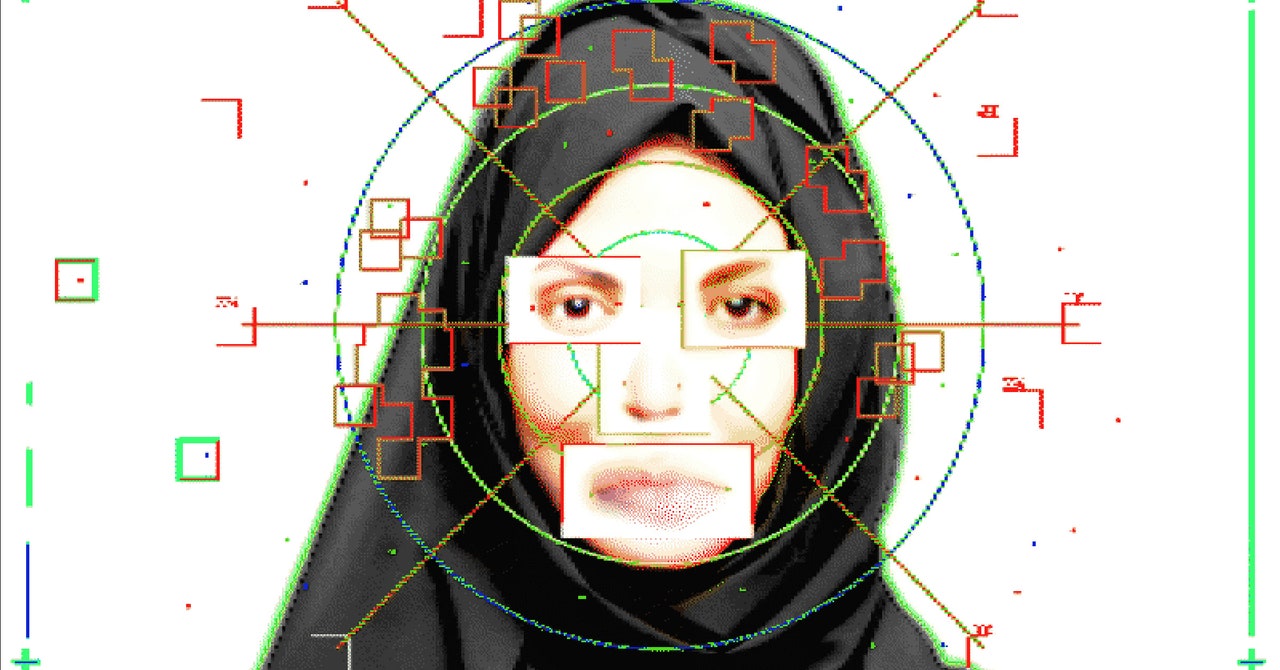

Like Alimardani, she has received reports from people using online platforms to organize in Iran who suspect they were somehow recognized and then targeted by authorities offline. Iran’s government has monitored social media to identify opponents of the regime for years, Grothe says, but if government claims about the use of face recognition are true, it’s the first instance she knows of a government using the technology to enforce gender-related dress law.

Face recognition has become a desirable tool for authoritarian regimes around the world as a way to suppress dissent, Grothe says, although many lack the necessary technical infrastructure. “Iran is a case where they have both the governmental will and the physical capability,” she says.

Multiple arms of the Iranian government have access to face recognition technology. Iranian traffic officials started using it in 2020 to issue fines and send women warnings by SMS text about wearing a hijab when inside a vehicle. Mousa Ghazanfarabadi, the head of the country’s parliamentary legal and judicial committee, spoke last year in support of “exclusion from social services and financial fines” for hijab violations. “The use of face recording cameras can systematically implement this task and reduce the presence of the police, as a result of which there will be no more clashes between the police and citizens,” he told Iranian news outlet Enghelabe Eslami.

Some face recognition in use in Iran today comes from Chinese camera and artificial intelligence company Tiandy. Its dealings in Iran were featured in a December 2021 report from IPVM, a company that tracks the surveillance and security industry.

Tiandy is one of the largest security camera manufacturers in the world, but its sales are largely within China, report author Charles Rollet says, and the company appeared to jump at the opportunity to expand into Iran. IPVM found that the Tiandy Iran website at one time listed the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, police, and a government prison labor organization as customers—agencies Rollet describes as “the kind of places that raise red flags from a sanctions or human rights perspective.”

In December, the US Department of Commerce placed sanctions on Tiandy, citing its role in the repression of Uyghur Muslims in China and the provision of technology originating in the US to Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. The company previously used components from Intel, but the US chipmaker told NBC last month that it had ceased working with the Chinese company. Tiandy did not respond to a request for comment.

Exports from China have contributed to a rapid recent spread of surveillance technology. When Steven Feldstein, a former US State Department surveillance expert, surveyed 179 countries between 2012 and 2020, he found that 77 now use some form of AI-driven surveillance. Face recognition is used in 61 countries, more than any other form of digital surveillance technology, he says.

In his recent book The Age of Digital Repression, Feldstein argues that authoritarian countries have largely managed to counteract the momentum of internet-enabled protest movements. “They have adapted and are using new tools to strengthen their hold on power,” Feldstein writes.

Despite deploying repressive technology and mass surveillance, in the past month both China and Iran have witnessed some of the largest protests either nation has seen in decades.

After a person dies, Shia Muslim custom calls for chehelom, a day to remember the dead 40 days after their passing. That tradition is now fueling protests in Iran, as remembrance of each of the more than 500 people killed since the death of Masha Amini triggers new waves of outcry.

A cycle of chehelom following the killing of hundreds of people by government forces led to the Iranian people overthrowing the shah in 1979. Alimardani of Oxford expects the cycle of current protests—which she characterizes as the largest and most diverse since the revolution—to continue, with young people and women taking the lead.