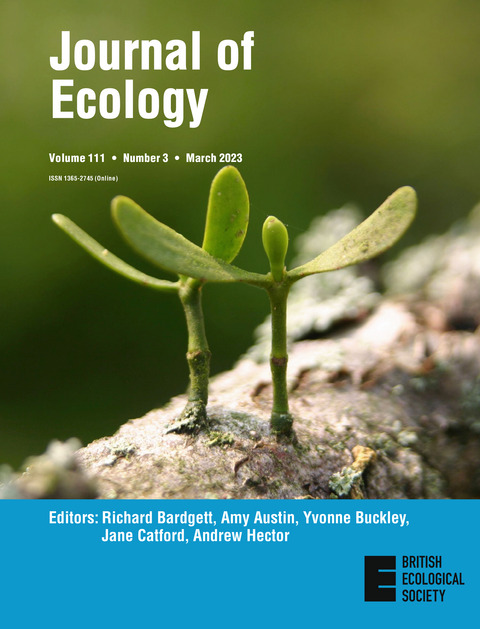

The cover image for our March issue shows twin seedlings of mistletoe (Viscum album) established on a branch of apple (Malus domestica), the parasite’s most frequent British host. This image relates to the Biological Flora of Britain and Ireland: Viscum album, by Peter Thomas et al. Here, co-author Jonathan Briggs tells us the story behind the image:

The germination of Mistletoe, Viscum album, is a rather mysterious process. Many gardening texts, often simply copied from each other, talk of cutting slits in bark, placing a seed inside and sealing it up. They usually follow this with a statement that germination success is rare. Which it will be, as planting mistletoe seeds like this is very likely to kill them!

Mistletoe seeds require light for germination, not burying under bark, and the emerging seedlings are adapted to connect to the host from outside the bark, not inside. The seedlings in the cover picture, which are three, perhaps four, years old, have gone through a slow, but initially external, germination process to get to this stage.

Mistletoe seeds are photosynthetic even when inside the ripe translucent berries, where the large green seeds are very visible to the naked eye. Birds taking these berries, with each seed in a gelatinous sticky mucilage within the berry skin, will wipe or excrete the sticky seed onto a surface, often a host branch. Once stuck in place germination can begin. Hypocotyl shoots emerge, in late winter or early spring, from the still green endosperm, regardless of where placed. This can be any surface, fence posts, buildings or even cars as well as branches. Indeed, if not taken by birds before April, seeds will readily germinate within each berry, still attached to the parent plant. Germination, contrary to gardening lore, is actually very easy.

The trickier stage is after germination, when the emerging hypocotyls seek to find suitable host bark. They will quest in vain on inanimate surfaces, though will survive many months as a thin, 1mm wide and 10mm long, independent (not yet parasitic) plant. These shoots bend round to contact the adjoining surface and, if that is suitable host bark, widen to a disc-shaped holdfast, about 2mm diameter, pressed against the bark. Many seeds are polyembryonic, sending out more than one shoot, so there are often two or more of these holdfasts close together.

Under that holdfast the young mistletoe, still an independent plant, begins to penetrate the host periderm, growing through to connect to the host xylem to begin the parasitic stage of growth. This stage takes about a year, with the endosperm often staying attached and probably helping support the young plants. By the second season the hypocotyls have detached from the endosperm and become erect, developing the first leaf pair during year two. Growth is slow in years three and four too, with each plant often only growing one more internode in the third year.

The twin seedlings on the cover picture have reached this stage and will now begin to grow in earnest, each shoot bifurcating once a year, to create the distinctive dichotomous branching shape of mistletoe. Each bifurcation, just one internode long and topped by paired leaves, doubles the number of shoots and leaves each season. And, since mistletoe, unconfined by ground contact, can grow in any direction, this mathematical growth is what results, eventually, in the familiar spheres of mistletoe seen high in host trees.