When high school English teacher Kelly Gibson first encountered ChatGPT in December, the existential anxiety kicked in fast. While the internet delighted in the chatbot’s superficially sophisticated answers to users’ prompts, many educators were less amused. If anyone could ask ChatGPT to “write 300 words on what the green light symbolizes in The Great Gatsby,” what would stop students from feeding their homework to the bot? Speculation swirled about a new era of rampant cheating and even a death knell for essays, or education itself. “I thought, ‘Oh my god, this is literally what I teach,’” Gibson says.

But amid the panic, some enterprising teachers see ChatGPT as an opportunity to redesign what learning looks like—and what they invent could shape the future of the classroom. Gibson is one of them. After her initial alarm subsided, she spent her winter vacation tinkering with ChatGPT and figuring out ways to incorporate it into her lessons. She might ask kids to generate text using the bot and then edit it themselves to find the chatbot’s errors or improve upon its writing style. Gibson, who has been teaching for 25 years, likened it to more familiar tech tools that enhance, not replace, learning and critical thinking. “I don’t know how to do it well yet, but I want AI chatbots to become like calculators for writing,” she says.

Gibson’s view of ChatGPT as a teaching tool, not the perfect cheat, brings up a crucial point: ChatGPT is not intelligent in the way people are, despite its ability to spew humanlike text. It is a statistical machine that can sometimes regurgitate or create falsehoods and often needs guidance and further edits to get things right.

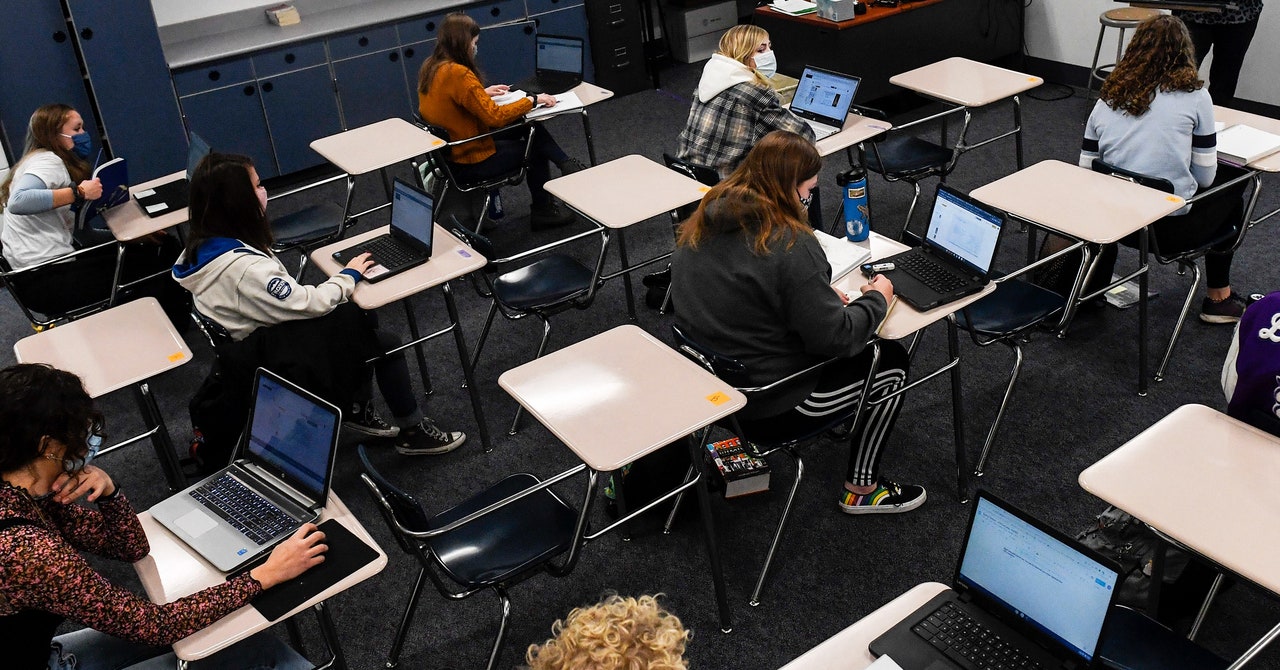

Despite those limitations, Gibson also believes she has a responsibility to bring ChatGPT into the classroom. She teaches in a predominantly white, rural, low-income area of Oregon. If just the students who have ready access to internet-connected devices at home can gain experience with the bot, it could widen the digital divide and further disadvantage students who don’t have access. So Gibson figured she was in a position to turn ChatGPT into, to use educator-speak, a teachable moment for all of her students.

Other educators who reject the notion of an educational apocalypse suggest that ChatGPT might not be breaking education at all, but bringing attention to how the system is already broken. “Another way of thinking about this is not how do you find new forms of assessment, but what are our priorities in further education at the moment? And perhaps they’re a little bit broken,” says Alex Taylor, who researches and teaches human-computer interaction at City, University of London.

Taylor says the bot has prompted discussions with colleagues about the future of testing and assessment. If a series of factual questions on a test can be answered by a chatbot, was the test a worthwhile measure of learning anyway? In Taylor’s view, the kind of rote questions that could be answered by a chatbot don’t prompt the kind of learning that would make his students better thinkers. “I think sometimes we’ve got it back to front,” he says. “We’re just like, ‘How can we test the hell out of people to meet some level of performance or some metric?’ Whereas, actually, education should be about a much more expansive idea.”