(Beirut) – Syrian government forces used widely banned cluster munitions in an attack on Termanin, a town in northern Idlib, on October 6, 2023, killing two civilians and injuring nine others, Human Rights Watch said today. The next day, a 9-year-old boy picked up a munition that had failed to detonate on impact during the attack. It exploded, injuring him and two others.

This attack was part of a larger military campaign by Syrian and Russian forces on opposition-held northwest Syria that started on October 5 and had, as of October 27, affected more than “2,300 locations” across Idlib and western Aleppo. At least 70 people have been killed, including 3 aid workers, 14 women and 27 children, 338 others injured, and 120,000 newly displaced, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

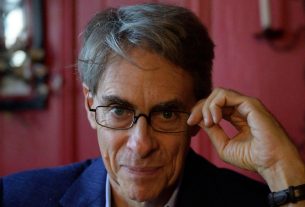

“Syrian government forces’ use of cluster munitions during its bombardment of opposition-held areas proves just how tragically indiscriminate these weapons are and their devastating legacy of lasting harm,” said Adam Coogle, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “Amid the ongoing bombardment by Syrian and Russian forces, the children of Idlib yet again fall victim to callous and unlawful military actions.”

The attacks, which in some instances involved the use of incendiary weapons, also damaged critical services and infrastructure, including 23 health facilities and hospitals and 17 schools, the UN said. By October 30, the Syria Civil Defence, a volunteer search and rescue group operating in opposition-held areas, reported that airstrikes and artillery shelling was continuing to damage residential areas, schools, and health facilities across the region. One October 24 airstrike hit a camp for displaced people near the village of al-Hamama in the western countryside of Idlib governorate, killing five members of the same family, including a pregnant woman, two infants, and their 70-year-old grandmother.

“We are witnessing the largest escalation of hostilities in Syria in four years,” Paulo Pinheiro, head of the UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria told the UN General Assembly on October 24. “Yet again there appears to be total disregard for civilians’ lives in what are often tit-for-tat reprisals.”

This most recent escalation by Syrian government forces comes in retaliation for a deadly drone attack on a military academy in Homs on October 5. The attack took place during a graduation ceremony for cadets, killing at least 120 people, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, an organization that monitors the Syrian conflict. Women and children were reportedly among the dead. All parties to the conflict must take all feasible precautions in the conduct of military operations to avoid, and in any event minimize, loss of civilian life and injury to civilians.

While no group has yet claimed responsibility for the attack, Syria’s Defense Ministry claimed in a statement that “armed terrorist groups” were responsible, without identifying a group. It vowed to respond “with full force and determination” and warned that those who planned and executed the attack “will pay dearly.”

Syrian government forces then intensified attacks across Idlib governorate, which is largely under the control of the anti-government armed group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, and is home to about three million people, half of them from elsewhere in Syria since the start of the conflict.

On October 12, Syria’s state news agency, SANA, quoted a Syrian military source stating that the Syrian army “will continue to pursue and strike [the “extremists”] until the country is cleansed of them.” The attacks on Idlib lasted through at least October 30.

Human Rights Watch interviewed five residents of Termanin, one of whom lost a brother in the cluster munition attack, which he said took place just before 11 p.m. on October 6. Researchers also spoke to first responders with the Syria Civil Defence, and analyzed videos and photographs taken just after the attack and in the days that followed that were uploaded to social media platforms or shared directly with researchers.

Human Rights Watch confirmed the authenticity and location of a video recorded in central Termanin shortly after the attack, which the Syria Civil Defence shared online. In the video, a man is seen lying on the ground, with his clothing soaked in blood. Members of the Syria Civil Defence carry him to a waiting ambulance. Shortly afterward, a second, younger male is carried to the same ambulance.

Syria Civil Defence told Human Rights Watch that the first man, whom they identified as Sami Bakro, died on arrival at the hospital. Syria Civil Defence said that the bombardment that night killed 5 civilians and injured at least 31 others.

Since the start of the armed conflict in Syria in 2012, Human Rights Watch has documented civilian harm from the Syrian government’s use of cluster munitions, including a November 6, 2022 attack on four camps for internally displaced people in Idlib.

Cluster munitions are fired from the ground in rockets, missiles, and projectiles or dropped from aircrafts. They typically disperse in the air, spreading multiple submunitions or bomblets indiscriminately over an area about the size of a city block. Many fail to explode on initial impact, leaving duds that can kill and maim, like landmines, for years or even decades, unless cleared and destroyed.

The 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions, which 112 countries have ratified and 12 more have signed, comprehensively prohibits these weapons and requires the clearance of contaminated areas, and assistance to victims. Neither Syria nor Russia are parties.

Incendiary weapons are designed to start fires and can cause excruciatingly painful burns, often down to the bone, and set fire to objects, infrastructure, and human bodies, with long-lasting and severe physical and social consequences.

Human Rights Watch has, since 2011, also documented hundreds of indiscriminate attacks by Syrian-Russian military forces on civilians and critical civilian infrastructure, including in Idlib and western Aleppo. Opposition-held northwest Syria is home to 4.5 million people, at least half of whom have been displaced at least once since the start of the conflict. Civilians in these areas are effectively trapped, lacking resources to relocate, unable to cross into Turkey, and risking persecution if they attempt to relocate to government-held areas. Most depend on humanitarian aid to meet their basic needs.

“The Syrian government’s statement threatening to ‘pursue and strike [the “extremists”] until the country is cleansed of them’ is of special concern, given its record of carrying out unlawful and indiscriminate attacks without regard for civilian lives,” Coogle said.

The October 6 Attack

Two Termanin residents said the attacks started sometime after 9 p.m. “We were all sitting together at home after dinner, like any family would, when we were surprised to hear the sounds of explosions in and near our town,” said 49-year-old Abdel Karim Bastin. He said that his 21-year-old nephew Anwar Bastin was killed shortly thereafter when a munition landed 10 meters away from them in a square next to his home where they were both standing. “We dropped to the ground and he held my hand as we did,” he said.

At around 10:50 p.m., the submunition payloads from two 220mm 9M27K-series Uragan surface-launched cluster munition rockets landed in two residential blocks within about 1 kilometer apart in central Termanin, Syria Civil Defence said. Human Rights Watch verified and geolocated a photograph it shared of one of the Uragan’s remnants embedded into the ground on a sidewalk next to a boys’ school in Termanin.

In an October 10 post to its Facebook account, the school shared images of the Syria Civil Defence appearing to check for remnants of cluster munitions around the school’s premises.

Photographs of remnants cleared after the attack by Syria Civil Defence show 9N235 or 9N210 fragmentation submunitions lying on the ground. Each 9M27K-series Uragan rocket has a range of 10 to 35 kilometers and contains 30 9N235 or 30 9N210 submunitions.

Shortly after the first string of explosions reverberated across Termanin, 50-year-old Taha Amouri took his family to an open field on the outskirts of town to shield them from the attacks. He later drove his 35-year-old brother Ahmed back into town to assist others affected by the bombardment.

“It was sometime before 11 p.m. [that I dropped him off],” Amouri said, after which bomblets from the cluster munitions attack struck Ahmed and his brother-in-law soon after Amouri drove away. Ahmed died from his injuries on October 10 at a Turkish hospital, Syria Civil Defence confirmed on October 11. As of November 2, Ahmed’s brother-in-law remained in a coma with severe injuries.

Because they feared further bombardment, Amouri told Human Rights Watch that he and his family chose to remain in the open field, where they slept for four nights.

Boy’s Injury on October 7

On October 7, 69-year-old Amoon Ahmad Bakro and her 9-year-old grandson were walking to the boy’s uncle’s house after buying bread in Termanin. Unaware of the danger, the boy picked up an item of unexploded ordnance and carried it for approximately 1.5 to 2 kilometers, to the house. Upon their arrival, the boy unintentionally dropped the munition outside the house, causing it to explode, injuring him, his uncle, and his aunt, both of whom were 10 to 15 meters away. “He had with him something he was playing with,” said Mahmoud Hammad, the boy’s uncle. “I didn’t have the time to react or to register what it was he was carrying in his hands.”

The boy was seriously injured and as of November 2 remained in the Bab al Hawa hospital in northwest Syria. His uncle has injuries to his arm and leg and his aunt to her hip and thigh.

Following the October 6 attack on Termanin, Muhammad Sami al-Muhammad, an explosives expert with the Syria Civil Defence, told Human Rights Watch that they cleared and destroyed 9 submunitions in Termanin. “Unfortunately, though, the boy getting injured, it happened faster than we could respond,” he said, noting the group’s volunteers were inundated with requests for help during the intensification in bombardment by the Syrian-Russian military alliance. Syria Civil Defence has been clearing explosive remnants of war since 2016.

Incendiary Weapons Attacks

Human Rights Watch has also found evidence that Syrian government forces used incendiary weapons, specifically ground-fired Grad-series incendiary rockets. Human Rights Watch confirmed the use of Grad incendiary rockets from the distinct images made by victims and first responders of an incendiary substance falling from the sky, identification of the remnants of the carrier rockets, and identification of the unique hexagonal-shaped capsules that contain the incendiary substance.

On October 18, an incendiary rocket landed on a house in Darat Izzah, killing a 13-year-old girl Mariam al-Helou and injuring her 11-year-old sister, who suffered burns to her arm, leg, and back. Other attacks with incendiary Grad rockets on the towns and villages of Darat Izzah, al-Atarib, Jisr-al-Shughur, and al-Abzimo on October 6,7, and 8, caused no deaths according to the Syria Civil Defence. In one attack on the village of al-Abzimo, it recorded injuries to three civilians, though none included burns.