By 2030, Germany aims to get 80 percent of electricity from renewable energy sources, and have 15 million all-electric cars registered.

But the expansion of wind energy there has been slow, and the car industry has come late to the electric vehicles market. Also, this energy transition requires significant amounts of minerals, such as lithium, cobalt, manganese, and copper: resources that are mostly located in Africa, Latin America, and Asia.

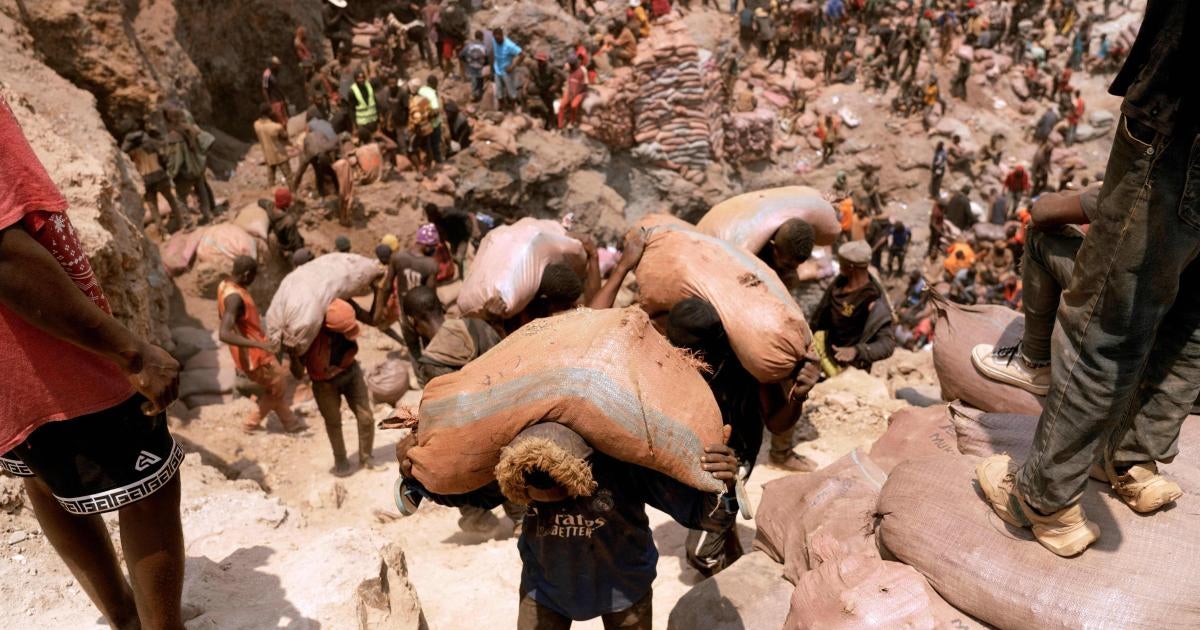

Given the human rights record of the mining sector – child labor, expropriation of land, pollution, violence by armed groups – the new rush on these so-called critical minerals is worrisome. It is therefore encouraging that the German government is addressing this conundrum. At a conference on “responsible mining for a just transition” last week, Development Minister Svenja Schulze recognised the risks, making clear that mine workers should be “able to do this work under decent conditions — that they are not exploited”.

But making this vision a reality is easier said than done. The majority of “critical” minerals are processed in China, where supply chains are rarely checked for risks of forced labor or other abuses. Germany and other EU governments are trying to reduce their dependency on China and to secure a diversified supply of minerals, proposed in the EU Critical Raw Materials Act. The Act relies heavily on certification initiatives and audits to decide whether new mines and other projects merit government support. But relying on audits or certifications is problematic, as they often lack rigor and transparency. The law therefore risks supporting harmful mining projects.

Mining for transition minerals is already characterized by violations, such as child labor in cobalt mining and violations of indigenous peoples’ rights in lithium mining. During the conference, Zambian activist Nsama Chikwanka gave a painful account of how mining for manganese and copper has caused pollution, illness, and loss of livelihoods in Zambia.

Germany’s new supply chains law entered into force in January 2023. The law obliges companies to identify, prevent, and address risks in their supply chains, and to report their steps publicly. Now, the office tasked with enforcement needs to closely watch companies in the supply chain for energy transition minerals, and impose fines on those that don’t comply. Responsible business conduct is just as critical as the minerals everyone wants.