The wastewater from your home – much like paper and plastic – can be recycled. This is done by sending it, including sewage, either to centralised municipal recycling plants, to local neighbourhood facilities, or even to facilities incorporated in large apartment buildings.

There, with the right technology, it is purified, and the resulting water can be used as normal for cleaning streets or watering plants. If the treatment process is thorough, it can even be used for drinking.

Fighting water scarcity

Recycled water is an important tool in the fight against water scarcity. It can help to reduce strain on our limited freshwater reserves, which make up only 2.5% of all the water on the planet.

In several parts of Spain, such as Alicante, it is already being used in farming, and in parks, gardens and leisure facilities. Elsewhere, including Singapore and Namibia, it is being used for human consumption.

However, in other parts of the world citizens have rejected the idea of recycling water, despite its safety and potential benefits. In some cases, this resistance has emerged after heavy government investment in infrastructure.

Imagine if your town or city proposed recycling wastewater. What would your reaction be? Whether you think it is a good idea or not, there are psychological factors that affect your decision.

Acceptance depends on use

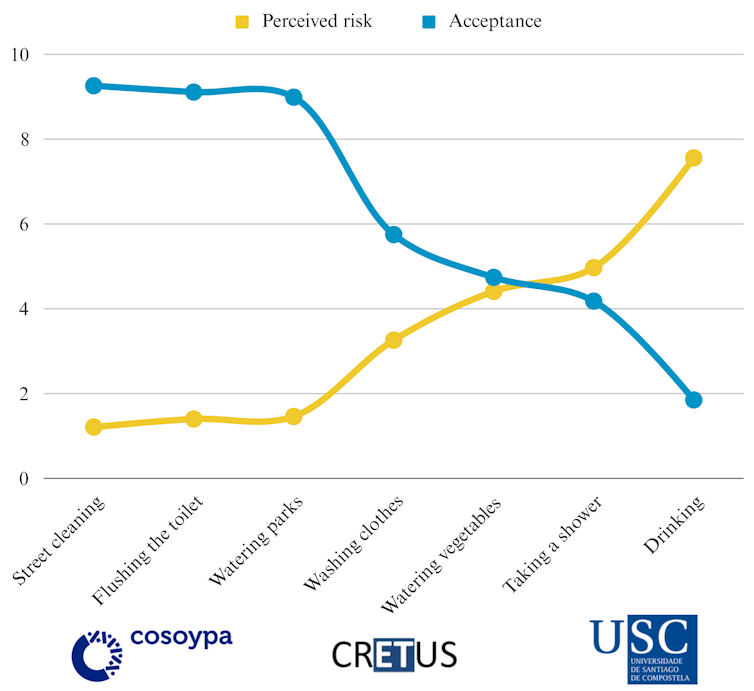

You might be OK with reusing water, but not in all situations, and there is actually a pattern with regard to which uses are seen as most acceptable. In essence, the more physical contact a person has with recycled water, the less likely they are to accept it.

Most people have no problem using recycled water to clean streets, but when it begins to touch our skin – for example in the shower – acceptance plummets. This is even more pronounced when it comes to ingesting it.

You might think that this pattern would not apply in a situation of objective scarcity: desperate times call for desperate measures, and people would, surely, be more open to recycled water in areas threatened by drought. You would, however, be mistaken.

Perceptions of scarcity

Curiously, acceptance levels are similar in areas that have totally different levels of water availability. This is evident within Spain, home to one of Europe’s wettest regions (Galicia) and one of its driest (Murcia). This uniformity raises the question of why acceptance drops as skin contact increases.

Author’s elaboration

Situations of scarcity have a definite impact, but more than hard statistics, it is our perception of scarcity that matters most: a negative event or situation has no impact if people do not interpret it as negative. Even when the danger is recognised, its effects may be perceived as distant in time or location, a phenomenon known as psychological distance.

Although the objective drought situation may differ between regions, what matters is how threatened people feel by it.

Recycled water is safe, but not everyone is convinced

You might be one of those people who would be repulsed if you found a hair in your soup. You might think the meal is ruined, and you may as well throw it away. When an item has been in contact with a contaminant, there is a tendency to believe that it has acquired its harmful properties forever, despite evidence to the contrary.

This logic of contamination applies to recycled water. Though treatment processes can guarantee that water has been completely purified – to the point where it is just as safe as regular tap water – people still feel it could cause them harm. For this reason, increased contact with water increases the perception of risk, drastically reducing acceptance.

Author’s elaboration

We have to remember, however, that people’s beliefs can change. We might like to think we can change our own perceptions, but many of them are moulded by our social exchanges. We might, for example, feel more open to using recycled water if the proposal came from a trusted source.

We also tend to observe and follow the majority, and low contact uses of recycled water (such as watering plants and cleaning streets) are already widely accepted. As these uses become more widespread, people will become more familiar with the processes involved, and will begin to recognise its benefits in confronting water scarcity.

This positive perception will then extend to other uses, marking a profound shift in our perceptions of responsible water use. One day, you might even find yourself going to a restaurant and ordering a bottle of recycled water, as if it were the most natural thing in the world.