The African Union has endorsed the #CorrectTheMap Campaign, a call for the United Nations and the wider global community to use a different kind of world map. The campaign currently has over 4,500 signatures.

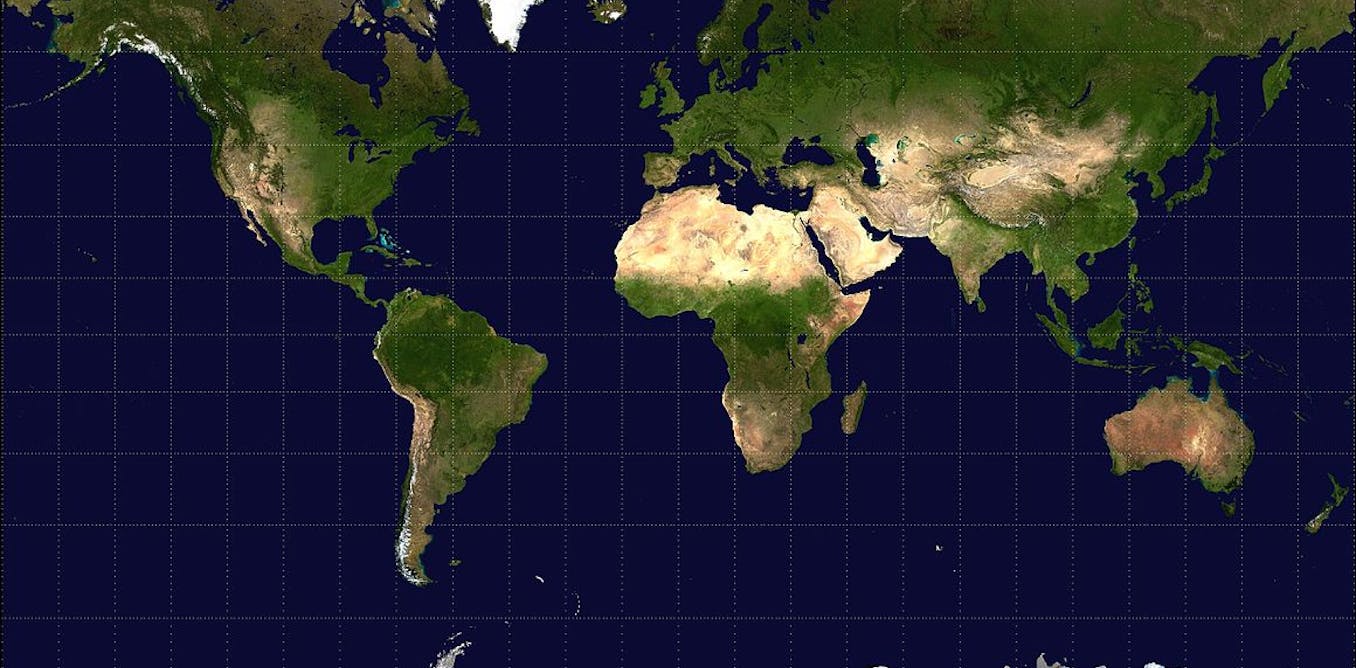

The map most commonly used is called the Mercator projection. Map projections are how cartographers (map makers) “flatten” the three-dimensional Earth into a two-dimensional map.

The Mercator projection was created over 450 years ago, designed for colonial exploration and maritime trade. But, over the centuries, it has become an “all purpose” projection for many governments, educators and companies.

That flat drawing inflates the size of countries closer to the North or South Pole. It exaggerates the area of North America and Eurasia while under-representing the size of much of South America and Africa. As the largest continent in the global south, Africa is a victim of this cartographic inequity.

The #CorrectTheMap campaign calls for a move to the Equal Earth map projection, developed in 2018 by an international team of cartographers. It addresses the distortions found in the Mercator projection.

Controversies over map projections are not new. Since the 1970s cartographers have discussed how certain projections distort how the Earth looks and how people imagine their place in that world.

At the heart of the debates about maps are tensions about what sort of power maps have in the world.

A change in map projections, for the African Union, is about more than correcting a technical flaw. It’s also a chance to influence how current and future map users view, talk about and value Africa.

The call is a demand for Africans to be represented on their own terms, rather than through cartographic traditions that have long diminished their scale and significance.

As cartographers, we pay attention to the social and communicative power of maps.

Given that maps help shape how we make sense of the world, the simplest decisions that go into crafting a map can have major geopolitical consequences.

Maps are not neutral

There are over 200 major projections of the world map. Each one warps the image of the Earth in different ways, making the choice of projection a consequential and complicated decision rather than a neutral one.

For example the Dymaxion projection, developed by the American engineer Buckminster Fuller, was designed to challenge ideas of the north and the south. Others, like the Lambert conformal conic projection, are used extensively in aviation to aid in flight planning.

Maps are a form of storytelling, as well as an information source. Even the lines, colours, symbols and size of regions depicted on maps communicate social meaning. They subtly but powerfully educate people, from schoolchildren to world leaders, about who and what matters.

US president Donald Trump’s recent interest in the US buying Greenland, citing its large size, was likely influenced by map distortion. The Mercator projection shows Greenland as nearly the same size as Africa, when in reality Africa is about 14 times larger.

Other projections do a better job at more accurately representing the true size of continents. Some projections are better than others for this specific task; for example the Gall-Peters projection has been used in the past as an alternative to the Mercator projection.

Cartography as a tool of control

Cartography has been a powerful tool of control throughout Africa’s history. Topographers and surveyors participated in the European conquest and colonisation of Africa, regularly accompanying military expeditions. Map-makers in Europe framed Africa as a landscape to be exploited by populating maps with trade routes, resources and blank spaces ready for development – all while often ignoring the mapping traditions and geographic knowledge of indigenous Africans.

The Berlin Conference of 1885, where European powers assembled with no African representation, was one of the pinnacles of this cartographic and colonial grab and partitioning of the continent.

The Mercator projection is joined by other kinds of western storytelling – found across popular culture, the news and diplomatic circles – that have stereotyped, degraded and undersized Africa’s place in the world.

Viewed in this light, the public reckoning over the Mercator projection can be interpreted as not just about the visual accuracy of a map, also the restoration of dignity and autonomy.

Why changing the world map is difficult

Bringing about changes won’t be easy.

Firstly, global map production is not governed by a single authority. Even if the United Nations were to adopt the Equal Earth projection, world maps could still be drawn in other projections. Cartographers are frequently commissioned to update world maps to reflect changes to names and borders. But the changes don’t always find quick acceptance. For example, cartographers changed English-language world maps after the Czech Republic adopted the name “Czechia” as its English name in 2016. While making the change was not difficult, broader acceptance has been harder to achieve.

A person’s mental image of the world is solidified at a young age. The effects of a shift to the Equal Earth projection may take years to materialise. Previous efforts to move away from Mercator projection, such as by Boston Public Schools in 2017, upset cartographers and parents alike.

Given the African Union’s larger goals, supporting the Equal Earth projection is the first step in pushing the global community to see the world more fairly and reframing how the world values Africa. Mobilising social support for the new projection through workshops with educators, diplomatic advocacy, forums with textbook publishers, journalists, and Africa’s corporate partners could help move the world away from the Mercator projection for everyday use.

Shifting to the Equal Earth projection alone will not undo centuries of distorted representations or guarantee more equitable global relations. But it’s a step towards restoring Africa’s rightful visibility on the world stage.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.