As children, many of us played the “telephone” game – a message is whispered from one person to the next, invariably getting distorted as it passes along the line. In this game, people’s perception and understanding matters more than the original message, but as the US Secretary of Defence James Schlesinger said in 1975, “everyone is entitled to his own opinions, but not to his own facts”.

Today, this statement applies to climate change. While there is broad scientific consensus that human action has contributed decisively to warming the atmosphere, ocean and land, causing widespread change in a very short time, public opinion is less clear. At least 97% of scientists agree that humanity contributes to climate change, but the same cannot be said for society at large.

Takver / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Same facts, different perceptions

Various studies and surveys show that social consensus on climate change is stronger in Europe than in the United States, where only 12% of citizens are aware of the scientific community’s near-total unanimity. This is a result of, among other things, disinformation, media portrayals, and cognitive bias.

Presenting climate change as a legitimate debate undermines the value of scientific consensus, often validating climate denialism – or its more recent iteration, delayism.

Moreover, there is a tendency to present ideological interpretations of the evidence as mere scientific disagreement: 82% of US Democratic voters believe that human activity contributes significantly to climate change, compared to just 38% of Republicans. This division also extends to responses to the crisis.

No enforcement, no accountability

The international community’s overall response has not been slow. As governments and multilateral bodies have become more aware of the issue they have committed themselves, albeit unevenly, to mitigation and adaptation plans.

This has also happened with decarbonisation plans, though, for the most part, commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, like those laid out in the 2015 Paris Agreement, are not binding.

This illustrates a clear obstacle to change: these commitments include no legal obligations, no effective enforcement mechanisms, and no accountability measures. This undermines any agreements, and their uneven and inconsistent implementation allows some countries to be “free-riders”, reaping the benefits of reduced emissions while contributing little to the costs.

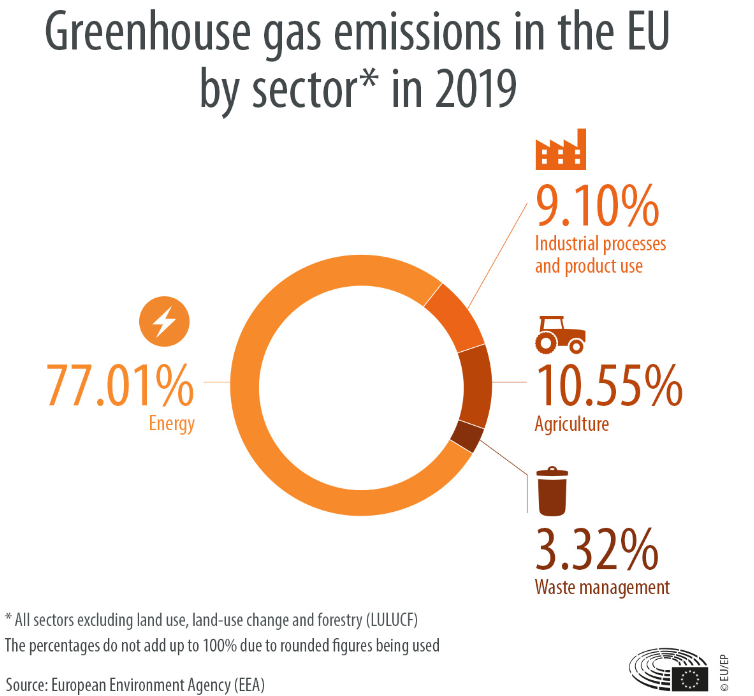

European Environmental Agency

Transition plans in companies and countries, and even in the global energy sector, consist of detailed strategies towards carbon neutrality and the goal of net zero. These cover a range of measures, from technological innovation to regulatory instruments, investments, and changes in individual and collective behaviour. However, confusion surrounding objectives like carbon neutrality and net zero is also a deterrent in many cases.

There has been some progress since the Paris Agreement in 2015, which projected emissions in 2030 under then current policies to increase by 16%. Today, a 3% increase is projected in the same period, but emissions would still have to fall by 28% to stay within 2°C of global warming, and by 42% to stay under 1.5°C.

Carbon dioxide emissions from China’s energy sector, for instance, increased by 5.2% in 2023. This means that an unprecedented 4-6% reduction in 2025 would be needed to meet the target.

Why can’t we slow down emissions?

There is no simple or singular explanation for humanity’s inconsistent attitudes towards climate change. It is an immensely complex issue, and only by recognising its complexity can we understand and try to change behaviours.

Despite slowing annual growth, global demand for fossil fuels has not peaked. It is expected to do so by 2030, but only if electric vehicle uptake increases, and if China’s economy grows slowly and it deepens investments in renewable energy.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Substantial amounts are still being poured into oil and gas investments. Between 2016 and 2023, they reached an annual average of around $0.75 trillion.

In 2023, global investment in clean energy reached an estimated $1.8 trillion, although concentrated in a few countries: mainly China, the European Union and the USA. For every dollar invested in hydrocarbons, approximately 1.8 dollars are already going into clean energy, but not all of it into renewables.

It should also be noted that long term “rebound effects” can often offset successful reductions in use of certain raw materials such as coal.

Furthermore, the benefits of carbon emission reductions are global and long-term, while the associated costs are often local and immediate.

Planet Labos / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Meanwhile, in low-income and emerging countries a lot of development is still less environmentally friendly – such as India’s ongoing dependence on coal – despite evidence that the co-benefits of reducing carbon emissions outweigh the cost of mitigation in a number of sectors.

Solutions remain elusive

It seems clear that there is no single solution. Some possible solutions require infrastructure or technologies to manage resources more efficiently, but more and more involve changes to our lifestyles and values.

In classical economics, the idea of rationality assumes that, with adequate information and income, an individual will always choose that which maximises their wellbeing. However, this explanation falls short – it assumes that people only live to maximise satisfaction through consumption, and ignores dreams, expectations and goals that may include other human beings.

The work of Herbert Simon in the 1950s demonstrates that our decisions are more accurately explained by what is known as bounded rationality: our cognitive capacity, information and time are limited, so we simplify reality and adapt.

For his part, Zygmunt Bauman’s conception of “liquid modernity” envisaged the transition from a solid modernity to a more fluid, unstable form, unable to maintain one set of behaviours for long, and much more prone to change.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

In the same vein, Gilles Lipovetsky speaks about the individualism and hedonism of a culture that prioritises the immediate fulfilment of individual desires, as opposed to commitment and sacrifice in service of ethical principles.

How do we reconcile these ideas that explain the way we respond to imperatives of sacrifice that, implicitly or explicitly, appear in the narratives of climate action and just transition?

Perhaps recognising complexity and trying to understand how we decide is part of the answer. Biases and inconsistencies are easier to detect in others than in oneself.