This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

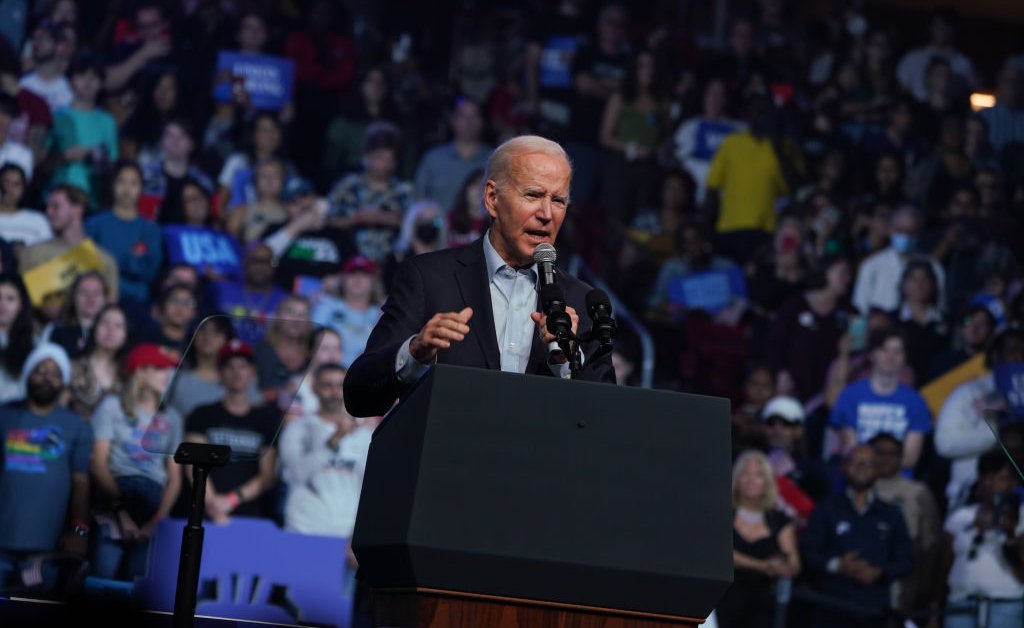

From the outside, the Democratic Party has been on a defensibly good run. President Joe Biden methodically notched wins, notably an early pandemic package that dwarfed Barack Obama’s two biggest accomplishments—the stimulus bill and Obamacare—combined, a bipartisan investment in infrastructure, and a climate-and-health agenda that stands to remake many Americans’ relationship with their government. He passed a second massive climate bill that, as an added bonus, capped some prescription drug costs. He also landed compromise—but incomplete—deals that provide for background checks on some gun sales, protect same-sex and interracial marriages, and bolster domestic production of semiconductor chips to counter China’s dominance.

Voters seemed to notice. Democrats beat historic trends at the ballot box this November, holding onto the Senate, expanding their footprints in state capitals and defending every legislative chamber, and fending off a thumping in the House. Biden’s once-dreadful standing with his own party’s base has quickly recovered, in part because he proved not to be a political albatross this fall.

Still, put a cork back in the celebratory bubbly, partisan Democrats. This is not a mandate, and the party’s brand remains in fixer-upper mode. Repair crews are now playing catch-up and hoping no one notices just how neglected the old place has become. As one particularly sharp election-eve warning put it, “if Democrats manage to hold on to the House and Senate, it will be in spite of the party brand, not because of it.”

The facts aren’t in dispute. Republicans won the popular vote this year for the first time since 2014. One Democratic research project found that the party was losing support as it sought to indict capitalism. Others, for months, warned that Democrats were taking voters of color for granted. Another survey showed a 55% majority of all voters saw the Democratic Party as preachy and too extreme, and none-too-loving of the U.S. of A.

Put frankly: Democratic wins this year were in large part because Republicans came off as more extreme in specific places, communities where 7% to 13% of reliable GOP voters just couldn’t pull the lever for Senate nominees in competitive races

After every Election Day, the smart donors always demand a report on how their dollars worked—or didn’t. Many of these groups on the left can all rightly claim degrees of victory. Still, none of the responsible groups should project that 2022’s lack of a drubbing is a model for the future; hoping the GOP nominates unelectable candidates on its own isn’t likely to be mistaken for a responsible strategy that keeps everyone at the table, and the table in one piece. But the long-simmering factionalism can only be masked for so long.

The rising progressive wing of the party may be loud and well-funded, but it didn’t exactly run the electoral ticket, having even odds of winning primaries and having poor chances of knocking off an incumbent Democrat. When the progressives tried to claim a scalp, they often just damaged the incumbents and drained their bank accounts. Just ask Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney who defeated a primary challenger championed by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez before narrowly losing his race this fall. Some candidates understood this well enough to ask the nation’s most prominent Democrat, Biden, to please, please, please stay away. Others, like Rep. Sharice Davids of Kansas, explicitly campaigned as someone willing to work across the aisle. She won a third term.

Between Labor Day and late October, Republican-allied groups spent $115 million on ads criticizing Democrats on crime and immigration in the top eight Senate races, a three-to-one ownership of that space. Public safety—aka “open borders” and “defund the police”—accounted for 45% of Republicans’ messaging in the final weeks. And, had Republicans not nominated some deeply flawed candidates, it may well have worked. Nationally, among voters who said crime was their top issue, they broke roughly 2-to-1 Republican. On immigration, that lopsided result was 3-to-1, according to exit polls.

Trump, even largely absent from the trail, boosted Democrats—at the polls and in fundraising. Still, inflation dominated the mindset this year, with 31% of voters saying it was their top issue; voters said they trusted Republicans more by a stunning 43-point gap. (Had it not been for a 53-point Democratic advantage among the 27% of voters who put abortion rights at the top of their list, this year’s results would have been far different.)

This isn’t just a campaign trail problem, either. The governing agenda on Capitol Hill is going to be perpetually acrimonious under a divided Congress. And even though Biden seems, for now, to have dodged any real threats to re-nomination, his White House is bracing for a constant drumbeat of investigations ranging from the partisan queries about Hunter Biden’s laptop and social media companies’ role in allegedly suppressing that story to the entirely reasonable questions about the United States’ hasty exit from Afghanistan. Democrats would do well to remember how Hillary Clinton’s entire record—especially her use of email—came to bleed into local races in 2016. Innuendo and misrepresentation are tough stains to clear. A damaged brand for one is a hurtful reputation for all. Democrats had braced themselves for a whalloping in 2022 that never arrived. They’re still staggering and stammering, but equally as unready for the sequel.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads From TIME