We’re taking part in Copyright Week, a series of actions and discussions supporting key principles that should guide copyright policy. Every day this week, various groups are taking on different elements of copyright law and policy, addressing what’s at stake and what we need to do to make sure that copyright promotes creativity and innovation.

It’s 1975. Earth, Wind and Fire rule the airwaves, Jaws is on every theater screen, All In the Family is must-see TV, and Bill Gates and Paul Allen are selling software for the first personal computer, the Altair 8800.

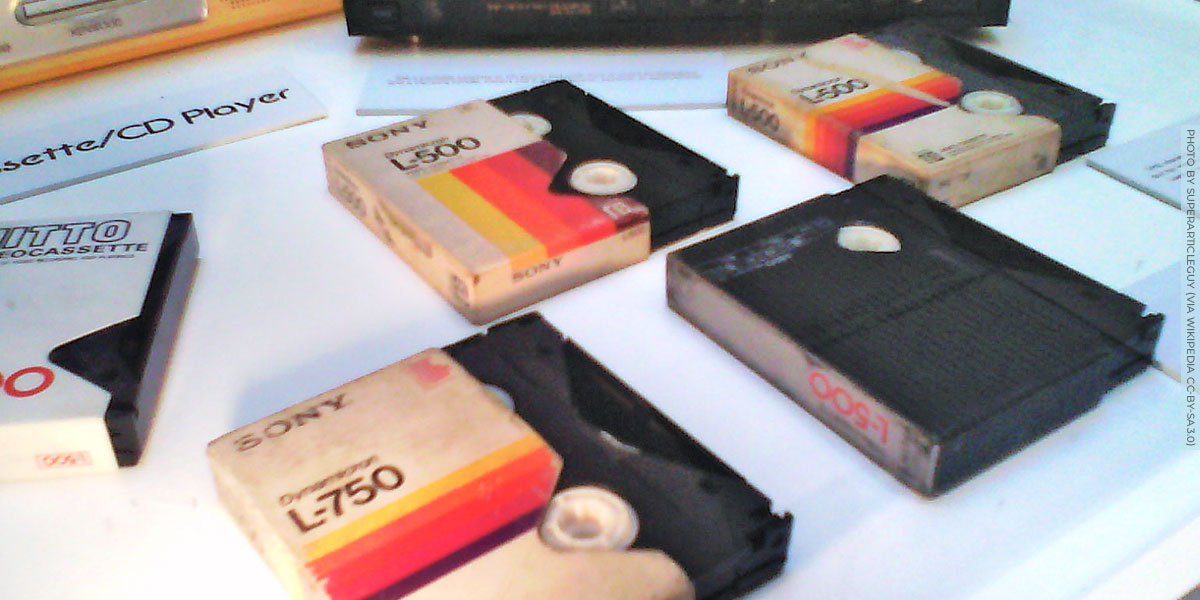

But for copyright lawyers, and eventually the public, something even more significant is about to happen: Sony starts selling the first videotape recorder, or VTR. Suddenly, people had the power to store TV programs and watch them later. Does work get in the way of watching your daytime soap operas? No problem, record them and watch when you get home. Want to watch the game but hate to miss your favorite show? No problem. Or, as an ad Sony sent to Universal Studios put it, “Now you don’t have to miss Kojak because you’re watching Columbo (or vice versa).”

What does all of this have to do with Generative AI? For one thing, the reaction to the VTR was very similar to today’s AI anxieties. Copyright industry associations ran to Congress, claiming that the VTR “is to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston strangler is to the woman home alone” – rhetoric that isn’t far from some of what we’ve heard in Congress on AI lately. And then, as now, rightsholders also ran to court, claiming Sony was facilitating mass copyright infringement. The crux of the argument was a new legal theory: that a machine manufacturer could be held liable under copyright law (and thus potentially subject to ruinous statutory damages) for how others used that machine.

The case eventually worked its way up to the Supreme Court, and in 1984 the Court rejected the copyright industry’s rhetoric and ruled in Sony’s favor. Forty years later, at least two aspects of that ruling are likely to get special attention.

First, the Court observed that where copyright law has not kept up with technological innovation, courts should be careful not to expand copyright protections on their own. As the decision reads:

Congress has the constitutional authority and the institutional ability to accommodate fully the varied permutations of competing interests that are inevitably implicated by such new technology. In a case like this, in which Congress has not plainly marked our course, we must be circumspect in construing the scope of rights created by a legislative enactment which never contemplated such a calculus of interests.

Second, the Court borrowed from patent law the concept of “substantial noninfringing uses.” In order to hold Sony liable for how its customers used their VTRs, rightholders had to show that the VTR was simply a tool for infringement. If, instead, the VTR was “capable of substantial noninfringing uses,” then Sony was off the hook. The Court held that the VTR fell in the latter category because it was used for private, noncommercial time-shifting, and that time-shifting was a lawful fair use. The Court even quoted Fred Rogers, who testified that home-taping of children’s programs served an important function for many families.

That rule helped unleash decades of technological innovation. If Sony had lost, Hollywood would have been able to legally veto any tool that could be used for infringing as well as non-infringing purposes. With Congress’ help, it has found ways to effectively do so anyway, such as Section 1201 of the DMCA. Nonetheless, Sony remains a crucial judicial protection for new creativity.

Generative AI may test the enduring strength of that protection. Rightsholders argue that generative AI toolmakers directly infringe when they used copyrighted works as training data. That use is very likely to be found lawful. The more interesting question is whether toolmakers are liable if customers use the tools to generate infringing works. To be clear, the users themselves may well be liable – but they are less likely to have the kind of deep pockets that make litigation worthwhile. Under Sony, however, the key question for the toolmakers will be whether their tools are capable of substantial non-infringing uses. The answer to that question is surely yes, which should preclude most of the copyright claims.

But there’s risk here as well – if any of these cases reach its doors, the Supreme Court could overturn Sony. Hollywood certainly hoped it would do so it when considered the legality of peer-to-peer file-sharing in MGM v Grokster. EFF and many others argued hard for the opposite result. Instead, the Court side-stepped Sony altogether in favor of creating a new form of secondary liability for “inducement.”

The current spate of litigation may end with multiple settlements, or Congress may decide to step in. If not, the Supreme Court (and a lot of lawyers) may get to party like it’s 1975. Let’s hope the justices choose once again to ensure that copyright maximalists don’t get to control our technological future.