I came to Advent as an Umbros-wearing ‘90s kid, sitting in the pews of a predominately Black cathedral in Ohio, waiting for someone to light a candle so the show could go on. Advent was a long yellow light leading up to Christmas, a ritualistic slowing down led by dudes in robes that reminded me my Christmas presents were close but just out of reach. And with the added liturgy and singing on those four Sundays, I’d have to wait an extra five minutes to grab a glazed doughnut in the back after Mass. How long, O Lord?

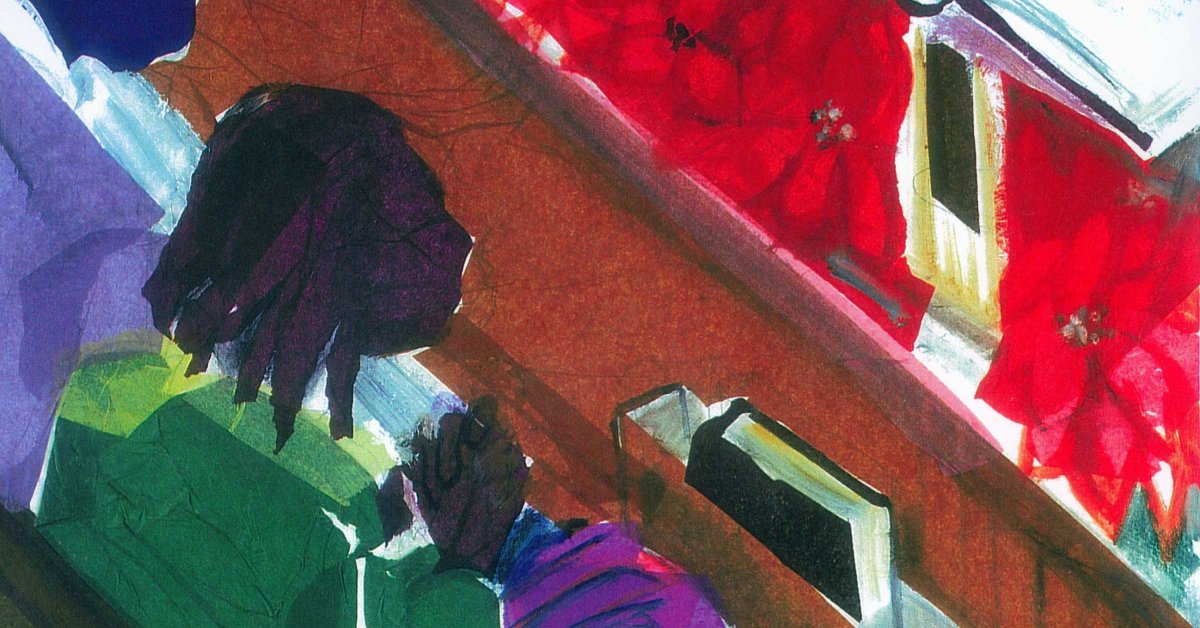

The only church tradition that kept my attention back then was the Christmas pageant. That’s when Mary, always embodied by a Black woman in a leotard and flowy skirt, danced across the stage to “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and my silly cousin, cast as an innkeeper, yelled at Joseph to go away while trying to keep a straight face. One year my grandfather, who’d served as Ohio’s first Black state highway patrolman, played the role of a magi, marching to the beat through the darkness of the center aisle.

I’m learning more about Advent as I near 40. I’m no longer Catholic, but I find myself looking back on Christmas at the cathedral with a new appreciation. For the meaning behind the rituals and liturgy, sure. It turns out the pink and purple candles aren’t just mismatched. They symbolize hope, faith, joy, and peace. And the waiting is intentional. It’s a designated time to sit in the mess and mystery of what it means to be human. To feel frail and uncertain, sad and disappointed. Angry at the imbalance of injustice to healing. We wait for the time when things will be made right. There’s a marked space during Advent for the sort of grief that can’t be cured by Starbucks red cups or Black Friday deals.

Read More: Why We Say ‘Merry Christmas.’ The Surprising Origins of 5 Christmas Traditions

But also, after 20 years of attending nondenominational and evangelical churches, I’m even more interested in the ways we, as Black parishioners, were integral to that church’s rendering of Christ’s birth. There was no cosmic story, no arrival of the Messiah, without us. No nativity scene worth beholding without our faces, bodies, and voices. We were central to the mystery and the hope. Not bystanders, nor passersby, nor stand-ins for a white or colorblind Jesus.

The priest didn’t just pluck a brown-skinned baby from the pews every winter to play Jesus. Throughout the year, a tapestry of a Black Jesus with an Afro hung above the altar, and our church had a gospel choir that sang Kirk Franklin songs, along with a minister of music who got down on the organ. When our white priest wanted to paint an image of Mary and Jesus, he asked my oldest sister to be the model. Do you know what it’s like to see your sister, your fierce protector and advocate, as the mother of God? It orients you to the cosmos in a way some Christians will have you believing is sinful or divisive. It reminds you that no matter what anyone says, you have never been an afterthought.

Read More: How Christmas Trees Became a Holiday Tradition

I never heard the sentiment “Jesus doesn’t see color” or “You’re being divisive” until I attended evangelical churches that prioritized whiteness. Sometimes I could sense it as soon as I stepped inside; other times, it took me longer to discern that my Blackness or “politics” were best checked at the door. I remember sitting in church as a young 20-something, wracking my brain over how to live as a person who loved Christ and loved being Black and studying our history. That divide existed in part because I’d listened to leaders who proclaimed that I was a “Christian first” and a Black person second. As though the two needed ranking for me to live in peace. As though my faith would be acceptable only if I discounted my skin, shed my body and, thus, myself, in service to a Common Denominator Jesus. The common denominator, while never articulated, always took the shape of American whiteness.

I am thinking about Advent now, as a mother of three Black children, wondering how I can shape my babies in both humility and enough-ness. Humility because Ain’t nobody Jesus but Jesus. And enough-ness because the world will threaten to break their spirits if they won’t part with themselves, swallow themselves, hide themselves. And one day, they might turn to the Church for comfort, only to find the same question being asked of them, dressed in Biblical language: Lose yourself, your Black self, for the sake of unity in Christ. Keep the bond of peace by keeping quiet.

As a Black mother, I’ve come to see Advent as both a home and a calling. On one hand, I am keenly aware of my personal lack and my need for Jesus. I feel at home in acknowledging the uncertainty of life, how little control I actually have as a mere human. On the other hand, I sense a deep calling to help my children understand they are not incidental to the story of Jesus coming to earth, and neither is their skin. Cole Arthur Riley, bestselling author and creator of Black Liturgies, a project that’s been a salve to me, writes, “Let us remind ourselves that there is goodness in our skin, our womb, our bones.”

For my family, sometimes that reminder looks like attending a Black Baptist church, the kind in which Herschel Walker might be offered the “right hand of fellowship” but never ever a vote. Some Sundays it looks like the five of us gathering around our scratched-up dining table to remember Jesus with tiny plastic cups of grape juice and wafers bought online. I show up with my caffeine addiction, the kids fight over who will collect the empty cups, and the 70-pound goldendoodle breaks up our prayer circle when he’s feeling left out. It’s far from orderly, but somehow it feels holy.

There’s so much I can’t promise my children, so many stories I cannot revise. But this Advent, as my family waits, we can tell the story central to our faith. And we can do it in the fullness of who we are.

More Must-Reads From TIME