As anti-immigration rhetoric surges across Europe and the United States, it is vital that we look beyond the fearmongering and analyse what is really going on. While human mobility is often presented as a burden, the truth is quite the opposite. It is an essential driver of economic growth, demographic resilience and cultural cohesion.

Ignoring this fact is not just a miscalculation – it flies in the face of both empirical evidence and the democratic principles that modern societies claim to defend.

Migration is also not a 21st century anomaly. From the Mediterranean diasporas of antiquity to the mass migrations of the 20th century, human history has been defined by movement. City-states, colonial empires and modern nation-states have been built – and rebuilt – through the movement of people, languages, knowledge and goods. Presenting human mobility as a threat ignores this historical pattern, and tries to turn the exception – isolation – into the rule.

Any political discourse that presents migrants as intruders, rather than as potential citizens or economic agents, is a dangerous distortion, not only in moral but also in strategic terms.

Migration drives economies

In 2016, an analysis by the McKinsey Global Institute drew some compelling conclusions. While migrants accounted for only 3.3% of the global population in 2015, they generated 9.4% of global GDP that year – about $6.7 trillion. In the United States alone, their contribution amounted to about $2 trillion.

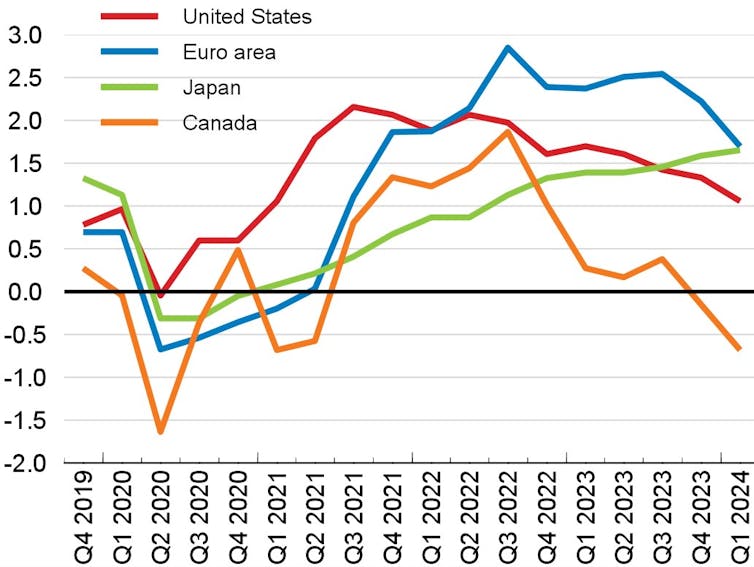

More recent studies confirm this. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated in 2024 that net migration flows to the eurozone between 2020 and 2023 – including millions of Ukrainian refugees – may raise the region’s potential GDP by an additional 0.5% by 2030. This is not a marginal amount, as it represents roughly half of all expected potential growth. Without migration, Europe’s economic horizon would be considerably more limited.

Read more:

Immigrants in Europe and North America earn 18% less than natives – here’s why

Workers, innovation, growth

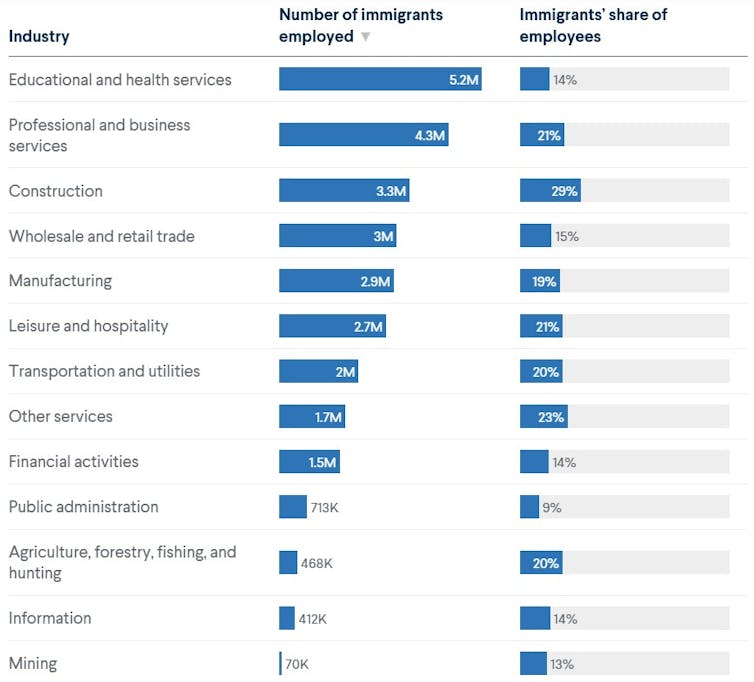

In the US, more than 31 million immigrants were part of the labour market in 2023 – 19% of the total, according to the Council on Foreign Relations. Their participation rate (meaning the percentage of the working-age population that is active in the labour market) was 67%, compared to 62% of native-born workers. This difference signals a disproportionate contribution to tax revenue, domestic consumption and economic dynamism in general.

Council on Foreign Relations

Statistics also show that immigrants do not compete on a level playing field: they tend to work in physically demanding jobs, or in those that are not covered by locals. This reinforces the idea that they complement, rather than substitute, native-born workers. This role becomes even more significant in contexts of full employment or population ageing.

Council on Foreign Relations

Migration and innovation

Migration brings not only workers, but also new ideas. According to the World Economic Forum, immigrants to the US are 80% more likely to start new businesses than native-born people, and more than 40% of Fortune 500 companies were founded by migrants or their descendants.

This pattern is repeated in academia and technology: a significant proportion of patents filed in the United States have at least one foreign inventor. The country’s leading universities also depend on international students to sustain their science, technology, engineering and mathematics programmes. In other words, closing borders means closing the door to innovation.

In the European Union, their impact is no less significant. According to the 2024 IMF report, between 2019 and 2023, two thirds of new jobs were filled by non-EU migrants. These statistics refute the idea that migrants “steal jobs”. On the contrary, they fill structural vacancies that neither automation nor the internal market has been able to fill.

Moreover, the OECD warned in 2025 that if more women, older people and immigrants are not brought into the labour market, GDP per capita growth in member countries could fall from 1% per year (2000-2020) to a meagre 0.6% by 2060. Conversely, a more inclusive migration policy could add at least 0.1 percentage point to annual growth.

OECD Economic Outlook, May 2024, CC BY

Sending money home

The 2024 World Migration Report confirmed that global remittances – immigrants sending money to family members in their country of origin – reached $831 billion in 2022, a growth of more than 650% from 2000.

This far exceeds official development assistance and even, in many cases, foreign direct investment. However, they perform a similar function – remittances are mainly invested in health, education and housing.

They are, in effect, a global redistribution of wealth that does not pass through any multilateral system. For the people who receive them, their impact is stabilising, and profoundly humane.

Looking forwards

This is not just a question of economics. When political and social rhetoric starts to exclude those perceived as outsiders, it undermines their capacity to adapt and change. Ignoring the evidence comes at a great cost, which can be summarised in three areas:

-

Economic losses: reduced immigration means giving up a structural source of growth, innovation and fiscal sustainability.

-

Social instability: anti-immigration discourse feeds the stigmas that fracture coexistence and weaken social cohesion.

-

Geopolitical weakness: less immigration means losing influence in a world increasingly defined by intense competition for talent and human capital.

The good news is that there are tried and tested solutions. From streamlining professional accreditation processes to regional migration coordination systems, there are already tools available to governments. The challenge is a political and, above all, narrative one. Public opinion – which is shaped by political rhetoric – needs to recognise and embrace the value of human mobility as part of our contemporary social contract.

As the World Economic Forum rightly points out, migration is not a problem to be solved, but a strategic asset to be managed intelligently and humanely. To underestimate it is to undermine the foundations of global development in the 21st century.