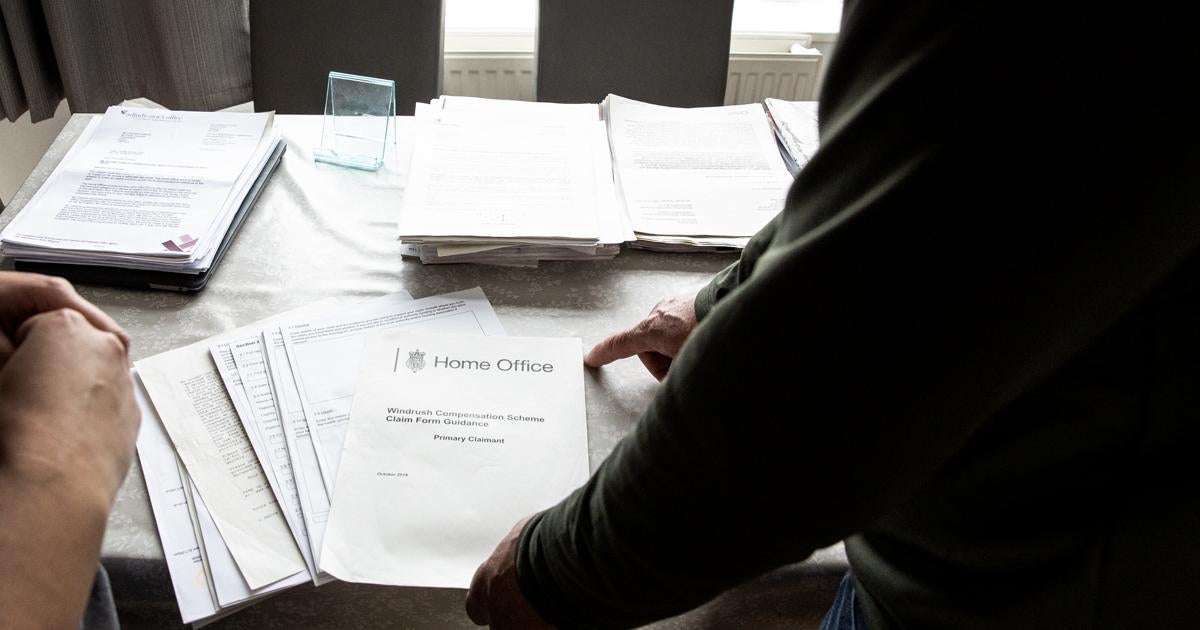

- A UK government scheme to compensate “Windrush scandal” victims is failing and violating the rights of many to an effective remedy for human rights abuses they suffered.

- The Windrush generation that has lived in the UK for decades have had to meet impossible requirements in recent years to prove their residency rights, causing life-altering losses.

- While an independent compensation scheme is needed due to significant procedural delays claimants have experienced, in the interim, transparent, independent oversight should be guaranteed, with access to legal aid and a right of appeal to an independent tribunal, as the current scheme is run by the agency that caused the problem.

(London) – A British government scheme to compensate “Windrush scandal” victims is failing and violating their right to an effective remedy for human rights abuses they suffered at the hands of the Home Office, Human Rights Watch said today.

On May 17, 2018, then-prime minister Theresa May apologized for the scandal, in which Black Britons who had arrived in the United Kingdom from the Caribbean after World War II were required, after living and working in the UK for decades, to meet impossible government requirements to prove their UK citizenship or residence rights. As a result, they lost jobs, homes, health care, pensions, and benefits. In many cases, they were detained, deported, and separated from their families.

“Five years after the Windrush scandal came to light, the Home Office compensation scheme is compounding its injustice by denying claimants their right to redress for the life-altering losses and negative effects it has had on their lives for years,” said Almaz Teffera, researcher on racism in Europe at Human Rights Watch. “The UK government should hand over the compensation scheme to an independent body that guarantees each claimant a fair and independent hearing.”

In April 2019, as part of the UK government’s responsibility to right the wrongs, the Home Office opened the Windrush Compensation Scheme to compensate members and relatives of the Windrush generation for losses and hardships they suffered as a result of not being able to prove their lawful status in the UK. The Windrush generation, who travelled with a legal right to live and work in the UK, was named after the HMT Empire Windrush, the ship that brought them to the UK.

Human Rights Watch interviewed over a dozen people with firsthand knowledge of the claims process in February 2023. Human Rights Watch found that the scheme is unfit for its purpose and requires urgent reform to protect the rights of claimants. The scheme should be independent, provide legal aid to claimants to assist with the complex application process, reduce the unduly high burden of proof for applicants, and provide meaningful avenues of appeal to address arbitrary decision making. As of January, only 12.8 percent of the estimated 11,500 eligible claimants had been compensated.

There was a strong consensus among those interviewed that, in the words of one claimant, the compensation scheme “was designed to fail the people who were supposed to benefit from it.”

The Windrush scandal became public in 2017 and widely known in April 2018. It affected thousands of citizens and lawful, long-term residents who arrived in the UK starting in 1948 as citizens of the UK or of former British colonies, but fell victim in the period after 2010 until present to what the UK government had called the “hostile environment policy.” The policy, a set of requirements reflected in UK immigration legislation, is designed to prevent access to services for anyone unable to prove their immigration status, with the stated aim of making the requirements so difficult that they would induce people to leave the country.

While the people who came to live in the UK from the Caribbean had a legal right to permanently live and work, the Home Office had failed to issue them documentation to prove their lawful status in the UK.

In 2022, a leaked internal report by a historian commissioned by the Home Office revealed that “during the period 1950-1981, every single piece of immigration or citizenship legislation was designed at least in part to reduce the number of people with black or brown skin who were permitted to live and work in the UK,” deeming citizens from former colonies not to belong to the UK. The Home Office told Human Rights Watch that the report would not be published because the views expressed in it were those of the author alone and did not represent government policy.

Wendy Williams, the author of the inquiry report, Windrush Lessons Learned Review, said that UK’s hostile environment immigration policy reflected “institutional ignorance and thoughtlessness towards the issue of race and the history of the Windrush generation within [the Home Office … and was] consistent with some elements of the definition of institutional racism.”

The Home Office has since admitted that its policies have a disproportionate impact on ethnic and racial minorities.

In 2020, a senior Black Home Office official resigned from the Windrush compensation team in response to what she said was the “complete lack of humanity” within the Home Office toward Windrush claimants, saying that she had witnessed a culture of racism among Home Office staff.

Human Rights Watch sent an overview of its findings to the Home Office on March 10, 2023, seeking input and comments, and received a response on April 4.

The UK’s Human Rights Act gives effect in domestic law to the right to an effective remedy under the European Convention on Human Rights, which requires that the remedy be adequate, prompt, and accessible. A similar right appears in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, both of which are legally binding in the UK.

The UN Committee Against Torture raised the Windrush scandal during the UK’s last review in 2019, noting “years of ill-treatment suffered by people from the Caribbean and other parts of the Commonwealth at the hand of immigration officials and other official bodies in the United Kingdom […] includ[ing] detention and deprivation of access to healthcare services and accommodation.”

The UN Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent said following its January 2023 UK visit that the Windrush generation had suffered “irreparable harm” and that redress was “imperative.” They recommended: “Reparations and restoration of rights to Windrush claimants should be equally simple, without complex application and reporting requirements and with all uncertainty resolved in favour of the claimant.”

“The failure of the Windrush Compensation Scheme and the scandal itself are connected to unresolved institutional racism that dates back to the British Empire,” Teffera said. “To avoid more Windrush-style scandals, the UK government should urgently reform its immigration system in response to international and national concerns about the existence of deeply rooted racism.”

For more details on the failures of the Windrush Compensation Scheme including evidence from those affected, please see below.

Inaccessibility, Inadequacy of the Windrush Compensation Scheme

The widely recognized MacPherson report, examining the racial motives behind the police killing of Stephen Lawrence in the UK, described “institutional racism” as a “collective failure” of an institution to deny services in a racially discriminatory manner in form of “unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness, and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people.”

The Windrush Compensation Scheme was established in April 2019, following a recommendation of the independent Windrush Lessons Learned Review. In the report, Williams described the Windrush scandal as an inevitable result of UK’s hostile environment, partially rooted in the Home Office’s “poor understanding of Britain’s colonial history,” and laid out 30 recommendations for reform, which the UK government promised to carry out. In January 2023, Home Secretary Suella Braverman backpedaled on three of the recommendations, including one to create a migrants’ commissioner.

Methodology

In February, Human Rights Watch conducted remote interviews with over a dozen people with firsthand knowledge of the claims process. Eleven of them, six men and five women, are claimants. Most claimants have received initial compensation offers from the Home Office and have appealed or are in the process of appealing compensation offers. They are between the ages of 29 and 69 and live across the United Kingdom, with the exception of one person who returned to Jamaica voluntarily.

They are a mix of primary applicants – those personally affected by the Windrush scandal – and close relatives affected through primary applicants. Human Rights Watch also spoke with lawyers, journalists, academics, and campaigners for improvements, including community activist Patrick Vernon and volunteers at Windrush Lives, a self-organization of Windrush claimants.

Windrush Compensation Scheme Lacks Independence

Claimants seeking compensation under the scheme have to apply to the Home Office, but they said they do not feel that they would get a fair hearing there, as it is the agency responsible for the injustices. Claimants and lawyers expressed concern that many eligible claimants do not come forward because of that dynamic or because they are afraid of dealing with the same government department that deported members of the Windrush generation.

Martin Forde, an independent adviser to the Home Office tasked with setting up the scheme, told the UK Parliament in 2020 he was “very troubled” that the Home Office would be responsible for the scheme because it is not typical practice for the body that caused the loss to control the amount of compensation awarded.

In April 2021, the Home Office appointed Professor Martin Levermore as the first ‘Independent Person for the Windrush Compensation Scheme’ to make an independent assessment of the scheme. A short assessment from March 2022 is available on the Home Office website, acknowledging criticism of the scheme but concluding that the scheme should not be removed from the Home Office. The UK-based nonprofit JUSTICE has said that his full assessments should be made public, and detailed updates should be provided, including whether staff are properly processing cases and recording information.

Claimants told Human Rights Watch that applying for compensation has been “stressful,” “overwhelming,” and “traumatic,” with many saying that the Home Office lacks compassion and treats claimants with suspicion.

Thomas Tobierre, 69, a Windrush primary claimant, said Home Office staff “call us customers. They say the customer’s always right, but we’re made to feel we’re always wrong. You can call me a victim but I’m not a customer.”

Charlotte Tobierre, 37, daughter of claimant Thomas Tobierre, said that claimants “need a compensation scheme for the compensation scheme. The scheme itself is so hostile, just like the hostile environment policy.”

Dominic Akers-Paul, 29, said that “people who had spoken to the media to pressure the Home Office received higher amounts of compensation,” but that people should not have to go through such lengths to get justice.

Complex Application Process and Lack of Legal Aid

The application form for primary applicants is 44 pages long and requires substantive evidence of losses and what it calls “impact on life” that claimants can demonstrate is linked to living without papers showing their lawful status.

The Home Office told Human Rights Watch that while the current version of the form is longer than previous versions, “the scheme has been designed to be as clear and simple as possible, so people do not need legal assistance to make a claim.”

Both primary and close relative claimants said they thought that legal aid was necessary to access the scheme because of the complexity of the application process. Lawyers working pro bono with Windrush claimants made the same point. A 2021 report by JUSTICE on the need to reform the scheme said that Home Office support to claimants is inadequate.

Martina Banton, 46, described the difficulties her 72-year-old mother had when applying because the forms were “complicated” and because older claimants “didn’t have the paperwork that was required as evidence by the Home Office.”

Paulette Thomas, 62, a primary applicant, said that none of the claimants have “a legal background or understanding of immigration policies, so it was a very difficult time for everyone.” She added that “a lot of people are confused and don’t understand whether they are eligible.”

Nicola Burgess, a solicitor at Greater Manchester Immigration Aid Unit who oversees the Windrush Legal Initiative, which currently assists over 40 Windrush claimants, said that one “needs legal input” to access the scheme because, despite the Home Office claims, it is an “onerous” process.

Lauren James, 29, whose father is a primary applicant, said that “the form is set up to discourage people from filling it out.”

Burgess and Anna Steiner, a solicitor and senior lecturer at the University of Westminster who co-founded the Windrush Justice Clinic that assists Windrush claimants, pointed to the Home Office team called We Are Digital, which is supposed to provide claimants with a “free independent adviser” to fill out an application said that “the service is limited to three-hour sessions where caseworkers meet with claimants to listen to their stories without being able to give legal advice on whether they are eligible under the scheme or the level of evidence that the person would need to prove their claim under the scheme.” Steiner said that claimants who used the digital scheme have reported that they did not find it helpful.

Steiner said, “it takes a minimum of 40 hours to prepare a claim, which includes making a detailed statement about the impact the ordeal has had on them. We do not have funds to pay for psychiatric reports but in my experience where we have been able to obtain such reports, they have made a substantial difference to the amount offered under the scheme.”

Burgess said that solicitors also “instruct forensic accountants to prove the actual real-life value of losses of claimants, including pension losses or property value where a person was forced to sell their family home. Without access to legal aid, it is impossible for most individuals to access the expert evidence required to support their claim.”

When designing the scheme, Forde advocated providing legal aid to claimants, but the Home Office rejected his recommendation. Forde told Parliament he thought the process was “fairly opaque to non-lawyers and to those who are not used to dealing with documentation.” He said that access to legal aid would speed up the process and protect claimants from re-traumatization.

Arbitrary Decision Making, Delays

The Home Office has created five categories of Windrush claimants based on their losses and how the lack of recognized lawful status affected them. Level 1 is described as “inconvenience, annoyance, frustration and worry, where the effect on the claimant was fairly short-lived (lasting up to a few weeks),” which the Home Office compensates with an award of £10,000. Level 5 is described as “Profound impacts on a claimant’s life which are likely to be irreversible,” with an award of £100,000 or in exceptional cases more. The Home Office’s Windrush Schemes Factsheet – January 2023 shows that by the end of January 2023, 100 claimants had received compensation offers of over £100,000, 677 had received offers between £30,000 and £100,000, 806 claimants had received offers of less than £30,000, and 1,497 claimants were deemed not eligible for compensation at all.

The Home Office told Human Rights Watch that in “July 2021, the Home Office published refreshed decision maker guidance which sets out clearly how decision makers should apply the balance of probabilities and go about gathering evidence” and that “[a]ll internal routes will be exhausted before asking for more information [from claimants].” The Home Office also stated that changes since December 2020 were “fully focused on reducing the time between claim submission and decision” and that the “evidence gathering process has also been improved.”

Akers-Paul described the approach as a “cookie cutter exercise” that is insensitive to people’s situations. James said that the Home Office does not explain why they reject a claim even when it is accompanied by substantial evidence of impact and loss.

Thomas called the Home Office’s grading “disrespectful.” “An ‘inconvenience’ is when you missed a bus,” she said, adding that the word “worry” in the definition of level 1 losses trivialized the serious impact she experienced. “This language is not empathetic of what I and my children went through in having to prove my status when I didn’t really need to,” she said.

All claimants interviewed said they had appealed their initial compensation offer. This was confirmed as standard practice by lawyers who assisted claimants. Steiner said in some cases where applications were resubmitted without new evidence the Home Office doubled its first compensation offer, suggesting that the reviewer did not pay close attention the first time around. Akers-Paul said that he had to yet meet a claimant who was happy with their initial offer.

Anthony Williams, 59, returned to Jamaica after feeling he was less than a “third-class citizen” in the UK. After serving 13 years in the British army, he received a call from his subsequent employer notifying him that his paperwork was not in line with immigration rules. He said he could not claim benefits or access health care, was forced to live on £120 a month, his military pension, for years, and could not see a dentist for his serious dental problems. The Home Office’s initial offer amounted to £18,500. “The Home Office tries to pay you as little as possible,” Williams said.

Roland Houslin, 54, a primary applicant and close family member of another applicant, had to wait 13 months for a compensation offer.

Thomas said that the Home Office should “treat people with respect and acknowledge their lived experience.” She said she was confused about why some members of the same family could be deemed eligible for compensation and not others, when their experiences were the same. She was frustrated with the Home Office approach of having multiple caseworkers for one family, which meant “receiving multiple letters with incorrect information, causing a lot of confusion and showing the mismanagement on their part.”

Burgess said that “there was just so much discretion for caseworkers at the Home Office and what one caseworker considers a level 3 case, another might consider a level 1. We have seen cases where individuals with quite similar cases had different outcomes. The consistency is lacking, which promotes unfairness and disbelief.”

Some claimants have waited for months and years to go through the claims process. The campaigns group Windrush Lives told the House of Commons’ Home Affairs Committee in 2021 that: “Time is of the essence for many claimants due to age [… and] because claimants’ lives remain on pause whilst waiting for the compensation process to be concluded. Many claimants are heavily in arrears and continue to incur debts whilst waiting to receive compensation.”

Unreasonable Burden of Proof Leaves Losses Uncompensated

Under the scheme, claimants can be eligible for compensation due to the impact on their lives of their inability to prove their status, such as family separation or the inability to travel to attend family events, and due to losses they experienced, such as denial of access to education, health care, social housing, benefits, or employment.

Forde told Parliament that when designing the scheme, he wanted the Home Office to take a “light” approach to documentary evidence required from claimants. He felt that a high standard of proof had no place in the scheme because it places an undue burden on claimants.

This advice was ignored. For example, if a claimant says they could not get a job, they are required to show that it was because of their inability to show they had lawful status. Requiring this link is unreasonable, Human Rights Watch said, because it might require tracking down a potential employer to seek a letter stating that the person was denied a job years ago due to a lack of status. Comparable difficulties apply to proving other losses, claimants said.

Both Banton’s mother and James’s father became homeless due to their inability to prove status and yet had difficulty proving their homelessness to the Home Office because they did not have official documentation establishing a link between their homelessness and lack of proof of lawful status. Letters from local councils demonstrating periods of homelessness were not deemed sufficient.

Akers-Paul said he lost educational opportunities because he did not have a British passport to go on international school trips and start an apprenticeship. He said he incurred substantial university fees and missed out on working experience and higher wages that the apprenticeship would have provided. The Home Office did not recognize this as a loss of educational opportunities.

Tobierre said he fell into debt because he could not work due to his inability to prove his status and because of the cost of getting his wife to and from hospitals for her terminal cancer treatment. He had to draw on his pension to cover living costs and expenses. While the Home Office provided what they described to him as a “hardship fund” to cover the exact amount of his debt, they failed to inform him it would be deducted from his compensation offer, and he continued to struggle to meet expenses.

Impacts or losses relating to pensions are not eligible for compensation under the scheme. The Home Office has said that this is “because of the variable and complex nature” of occupational and private pension calculations. The Home Office provided another justification to Human Rights Watch, claiming that such calculations “would considerably increase the length of time taken to resolve claims.” Delays are “very problematic given that many claimants are approaching pensionable age,” the Home Affairs Committee said in November 2021 tasked to examine the Home Office’s administration and policies. The Home Office used the same rationale to exclude calculations of loss of future earnings and told Human Rights Watch that such loss of opportunity determinations would be “extremely difficult to assess in a fair and consistent manner.”

In a first High Court challenge to the scheme was in February 2023, with an 82-year-old claimant is fighting for 34 years’ worth of compensation for losses of employment and benefits when the Home Office only granted her £40,000 for “impact on life.” This case could have wider implications for other Windrush claimants, Human Rights Watch said.

Lack of Effective Appeal Rights

The agency’s lack of independence is compound by a lack of effective appeal rights. It has a two-tier appeal system. Appeals are known as “reviews.” Tier-1 reviews take place within the Home Office itself. Tier-2 reviews go to an “independent adjudicator,” in the UK’s tax authority, His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs. Tier-2 adjudicators can only make recommendations to the Home Office, though, even if it decides to uphold its initial determination.

Home Office statistics show that reviews have increased between 2019 and 2022, which indicates growing dissatisfaction with initial Home Office decisions. As of January 2021, 198 decisions had been submitted to a Tier-1 review, a number which grew to 853 as of January 2023 – a more than four-fold increase. The Home Office told Human Rights Watch that out of the 853 requests for review, 490 had previously been dismissed as not being entitled to compensation. Fewer claims result in Tier-2 reviews, with the cumulative total of 212 as of January 2023. Home Office statistics don’t provide information about how many initial determinations are overturned by the Home Office following a Tier-2 adjudicator’s recommendation. In its communication to Human Rights Watch, the Home Office mentions that out of 192 concluded Tier-2 reviews, in 139 claims the Home Office upheld its initial determination, 24 claims for review were withdrawn, and in only 29 claims did the Home Office revise its initial determination – 13 of which resulted in an increase in the initial compensation offer.

Burgess said it “can take clients months, if not years” to get to a Tier-2 review, and that “there should be a right of appeal to an independent tribunal once a decision has been made by the Home Office.”

Burgess and Steiner suggested that appeals should instead be heard by the Tribunal Service, which would be less costly and formal than through courts, yet still provide a review by independent judicial bodies. The Tribunal Service has chambers on asylum, employment, benefits, and criminal injuries, which means they come with expertise in matters relevant to the scheme. “Individuals should get their day in court and explain their case to a judge,” Burgess said.

Steiner said that “many claimants are deterred from a second appeal because by that point they have already had two refusals from the Home Office, are exhausted, and may give up on the idea of getting a fair hearing.”

Very few claimants have approached a member of parliament to submit a complaint to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman, who, similar to Tier-2 adjudicators, can only make recommendations to the Home Office. They cannot rule on the amount of compensation. Steiner said, “it is not an easy process.” However, complaints that have been taken to the ombudsman have led to damning reports on the scheme’s shortcomings. The Home Office told Human Rights Watch that of five Windrush compensation cases before the ombudsman, the Home Office changed its initial decision in two cases, with the others still under investigation.

Recommendations to the Government

To ensure its credibility with claimants, remove the Windrush Compensation Scheme from the Home Office and identify or create an independent and neutral body or organization to operate it.

Given the significant procedural delays claimants have experienced, in the interim, direct the Home Office to ensure more transparent, independent oversight over its administration of the scheme, including quarterly, detailed public reports on the scheme’s operation by the independent assessor.

Ensure that legal aid is guaranteed to all eligible claimants. Providing legal aid to claimants would also help limit arbitrary decision-making and most likely would speed up the process by ensuring more timely processing of applications by the Home Office.

Provide claimants with the right of appeal by an independent and impartial tribunal and make such appeal decisions binding. This is essential to ensure that there is an effective review of decisions.

Lower the burden of proof for claims and compensate fully for losses and impact on life, regardless of the complexity.