- At least several hundred people are in prison in Tunisia solely for writing checks they were later unable to pay. Many others facing charges are in hiding or exile.

- The practice amounts to debt imprisonment, which destroys families and businesses, and violates international law.

- Tunisia should replace this system with alternatives to prison for repaying debt; debtors should be released and allowed to establish a repayment plan.

(Tunis) – At least several hundred people are in prison in Tunisia solely for writing checks they were later unable to pay, Human Rights Watch said in a report published today. The practice amounts to imprisonment for debt, which violates international human rights law, and which destroys families and businesses.

In the 41-page report, “‘No Way Out’: Debt Imprisonment in Tunisia,” Human Rights Watch documents the consequences of Tunisia’s archaic legislation on checks with insufficient funds. The law, in addition to sending insolvent people to prison, or to live in hiding or exile, fuels a cycle of indebtedness and reduces entire households to lives of hardship. In the context of Tunisia’s current economic crisis, the authorities should urgently replace the legal provisions that allow for debt imprisonment with legislation that distinguishes between willful refusal and genuine inability to pay.

“Imprisonment for unpaid debt is an anachronism and is both cruel and counterproductive to ensuring that creditors recover their due,” said Salsabil Chellali, Tunisia director at Human Rights Watch. “When debtors remain free, they have the possibility of earning income to gradually repay their debts, while supporting their own households.”

On May 22, the Prime Minister’s Office announced in a statement that the Council of Ministers had approved a bill to amend legal provisions on unpaid checks, which suggests reduced prison sentences and financial penalties, and provides for alternatives to prison, among other measures, the statement says. The bill has been submitted to the Assembly of People’s Representatives for debate.

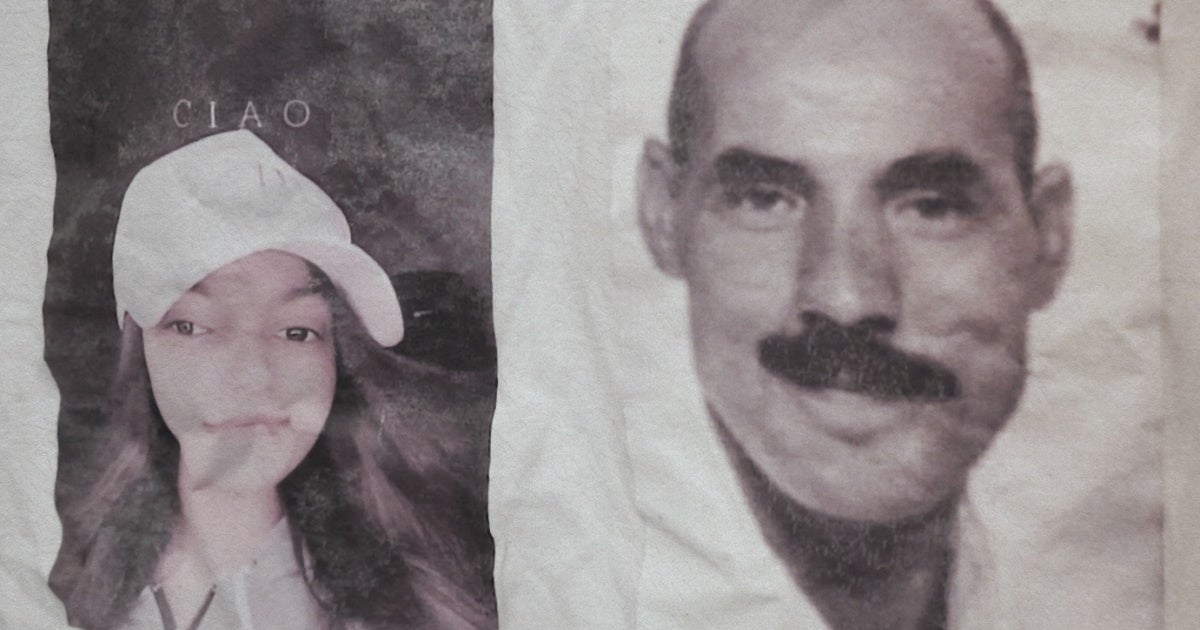

Human Rights Watch documented the cases of 12 people prosecuted for unpaid checks, including people imprisoned and others living in hiding or in exile.

Although originally conceived as a means of payment, checks in Tunisia are in practice widely used as a means of obtaining credit, especially in the commercial sector where they enable entrepreneurs to secure commercial goods or services in exchange for a check they provide that is to be cashed later, at an agreed-upon date.

Given the difficulties faced by micro, small, and medium-sized businesses in accessing bank financing due to the lack of collateral or the bank’s financing conditions, many in the commercial sector rely on this practice, known as the “guarantee check.”

When people who have issued “guarantee” checks are unable to later pay them, they risk imprisonment, as an unpaid check is considered a criminal offense punishable by up to five years in prison under Tunisia’s Commercial Code. While according to the government, 496 people were imprisoned for unpaid checks as of May 2024, a business association that focuses on this issue, the National Association of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises,estimated that this number is closer to 7,200 people, and that the authorities are seeking thousands more for unpaid checks. Such prison sentences are cumulative.

Those imprisoned often face stigma, and the lack of income while they are in prison or trying to escape prosecution can affect the enjoyment of their human rights, including access to basic services such as health care, housing, or education. Debt-induced economic woes may be compounded by the shortcomings of Tunisia’s public services and social security system.

In one case documented, Mejid Hedhli, a building contractor, was sentenced in 2016 to 122 years and nine months in prison over about 50 checks. Hedhli was renovating a public building in 2010, but its construction suffered delays and material damage after events during the 2011 revolution. His family also says that the public institution that contracted him did not fully pay him.

“If Mejid hadn’t been in prison, he could have worked and paid off all his checks,” said his wife, Jalila Hedhi. “His life has been squandered, and yet the checks remain unpaid.”

Interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch show that when a first check is rejected by the bank, the debtor often faces spiraling costs due to fines and fees and to other creditors seeking prompt payment. Crushing debt and the risk of imprisonment often leads people to cease all economic activity and go into hiding or flee abroad.

The current legislation unjustly fails to distinguish between a debtor unable to pay for compelling economic reasons and a person who used the check with fraudulent intent, Human Rights Watch said.

The debt can also burden the debtor’s extended family members, who often step in to help repay part of the debt by selling their own assets or taking bank loans. It also has negative consequences on the health of the indebted people and their family members.

Indebted people rarely have access to effective legal representation for unpaid checks, either due to lack of means or out of resignation when faced with the inability to settle the debt. Yet, the presence of a lawyer is particularly important when it comes to requesting a deferral of the hearing and giving the debtor more time to raise the required sum. If the debtor can pay their debt before the court pronounces a verdict, the prosecution is halted.

Because issuing these checks is considered a formal offense, the judge is not required to consider the intention of the check issuer, to examine the circumstances that led to the indebtedness, or to find alternatives to imprisonment.

Imprisonment for unpaid checks rarely leads to the creditor’s repayment, especially when the debtor is poor. In cases in which repayment is made, it is generally due to pressure on the debtor’s family members, who might pool funds to help.

President Kais Saied supports an amendment to the law and, in 2023, instructed Justice Minister Leïla Jaffel to introduce a bill to decriminalize these checks. Economic players such as Tunisia’s largest employer organization, the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade, and Handicrafts, recommended alternatives to imprisonment in July 2023. In February, lawmakers submitted a bill to grant amnesty to people prosecuted for these checks, but it has not yet been debated.

Tunisia should rapidly replace legal provisions allowing for debt imprisonment with legislation that considers the reality of using checks as a credit tool, provide alternatives to imprisonment, and provide sustainable means for creditors to recover what they have lent. People unjustly imprisoned under this law should be released and permitted to establish a debt repayment plan, as should those in hiding or exile.

Tunisia, which lacks a personal bankruptcy law that would provide relief for debtors facing economic hardship, including entrepreneurs in the informal sector, should also adopt legislation on personal insolvency.

“The Parliament should amend the law to effectively get indebted people who had no intention to default out of prison and out of a downward economic spiral,” Chellali said. “This is also an opportunity to put in place better protections against insolvency, and to adopt measures that benefit the economy in the longer run.”