Each year recently has felt tumultuous, marked by some moments of joy but also much upheaval and tragedy. This year brought new conflicts and celebrations, but it was no less turbulent. We encountered the start of a war, the overturning of a constitutional right, and a scientific discovery that evokes feelings almost too difficult to put into words.

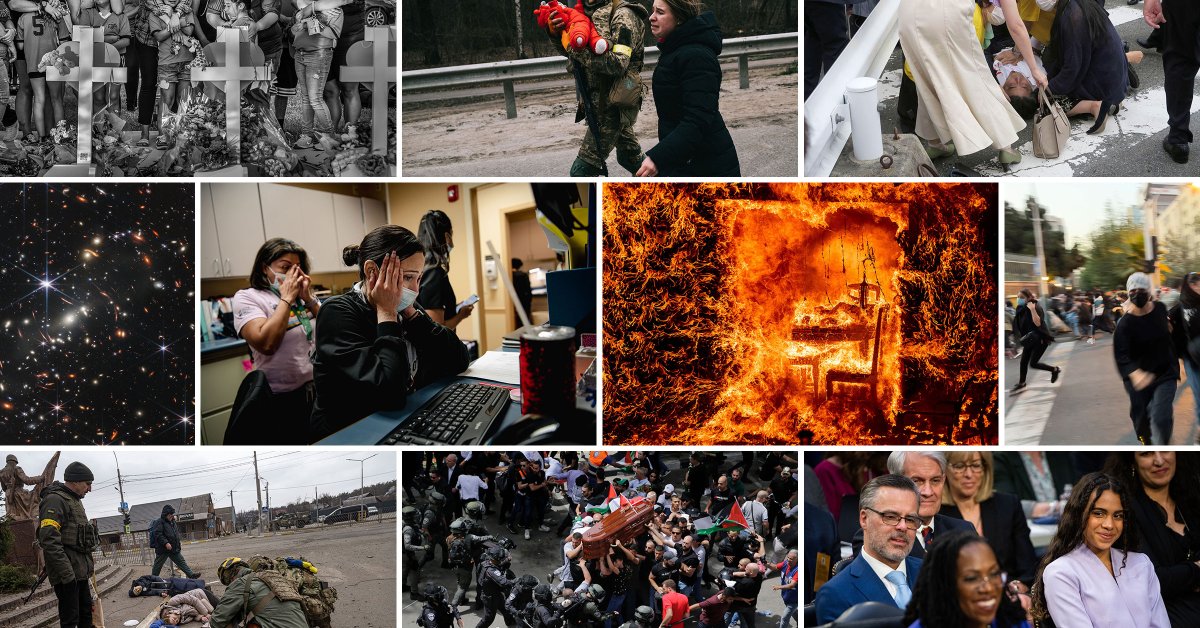

In selecting the 10 most impactful images of the year, the TIME photo team considered the scenes they document as well as what those moments represent to the country and the world and what it took for the photographers to capture them.

Meridith Kohut’s image from inside the Houston Women’s Clinic forced us to see what the reversal of Roe v. Wade meant for not only people seeking abortions but for those who care for them. David Butow’s photograph from a memorial in Uvalde, Texas, demanded that we face the effects of gun violence and the resulting grief. Sarahbeth Maney’s image from inside the confirmation hearings for Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson brought to the forefront the importance of having women of color and Black photographers documenting history. As we embark on a new year and all the unexpected events it is sure to bring, these photos will serve as a reminder of the moments that defined 2022.

Warning: Some of the following images are graphic in nature and might be disturbing to some viewers.

Israeli police confront mourners as they carry the casket of slain Al Jazeera veteran journalist Shireen Abu Akleh during her funeral in east Jerusalem, on May 13. Abu Akleh, a Palestinian-American reporter who covered the Mideast conflict for more than 25 years, was shot dead during an Israeli military raid in the West Bank town of Jenin.

Maya Levin—AP

‘In an Often Violent Landscape, That Day Feels Singular’

On May 11 Palestinian-American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh was shot and killed in Jenin while reporting on Israeli raids. Her death was a shock to the world and weighed deeply on the journalistic community. Two days after her death, fellow journalists and mourners gathered at the hospital, photographer Maya Levin among them.

“I was angry and am still angry that a person so clearly marked with a press flack jacket and helmet, surrounded by other journalists, could have been shot as she was,” says Levin. “This was at the forefront of my mind that day.” Palestinian colleagues of Abu Akleh wanted to honor her by carrying her through the streets of East Jerusalem, to allow others to pay their respects, but what was hoped to be an honoring tribute soon turned violent.

“The Israeli police barred the way out of the courtyard and began to beat the mourners and pallbearers back while they held her coffin,” Levin says. “Usually in situations like that it is better to be on the ground where the action is, but I wanted to get away from the tension that was building below and see what it was like from above.” She maneuvered to a high vantage point where she was able to capture this image. “In an often violent landscape, that day feels singular. What should have been a respectful day of mourning was instead violated by an aggressive police action.”

Flames engulf a chair inside a burning home as the Oak Fire burns in Mariposa County, Calif., on July 23.

Noah Berger—AP

‘One of the More Visceral Images I Shot This Season’

According to California’s firefighting agency Cal Fire, 15 of the top 20 most destructive wildfires have occurred in the past seven years. Photographer Noah Berger has covered 14 of them.

“Covering wildfires effectively requires a different mentality and skill set from a lot of the assignments I photograph during the year,” explains Berger. “It often means sleeping in my car for days, working up to 40 hours straight and carrying everything I need to stay self-sufficient in a chaotic environment.”

Throughout July, the Oak Fire tore through communities near Mariposa, Calif., destroying more than 125 homes while exhibiting what fire officials called “explosive fire conditions” including wind-born embers sparking spot fires up to two miles ahead of the main fire front. A forest-service spokeswoman explained to Berger that persistent dry conditions throughout the state meant that “the window for safety is much smaller for firefighters and residents.”

After driving a stretch of roadway with active fires on both sides, amid falling boulders and trees, Berger took this frame at 1:44 a.m. “This frame is one of the more visceral images I shot this season,” he says.

Women run away from anti-riot police during a protest of the death of a young woman, Mahsa Amini, who had been detained for violating the country’s conservative dress code, in downtown Tehran, Iran, on Sept. 19.

AP

Documenting Defiance

Three days before this photo was taken, on Sept. 19 in downtown Tehran, a young woman named Mahsa Amini was declared dead. She had been in the custody of the so-called “morality police,” who, by dint of enforcing the dress code of the Islamic Republic of Iran, had made themselves the most obnoxious expression of a regime suddenly facing its most serious internal challenge since coming to power 43 years ago. At word of Amini’s death, street protests had broken out in dozens of cities across the country, a spontaneous and leaderless uprising that continues four months later, despite hundreds of deaths and more than 18,000 arrests.

No foreign journalists are permitted inside Iran, but in this image obtained by the Associated Press, the forces in play are all visible: Young women have led the rebellion, united by the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom.” Some choose to wear hijab, others defiantly do not. And some dress for battle with the security forces that contest control of the streets aboard motorcycles, swinging clubs and firing buckshot. On the right is a fire set by protesters, who overturn trash bins and set them alight, both to claim the streets, and, in the approaching night, to sing and dance around. Even the blurring is apt, for a situation very much in flux. – Karl Vick

Patrick Jackson, left, husband of Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson, center, and daughter Leila Jackson, right, look on during confirmation hearings in Washington, on March 21.

Sarahbeth Maney—The New York Times/Redux

‘Document Our Own Experiences’

Photographer Sarahbeth Maney was working as a photography fellow for the New York Times in Washington when President Biden announced he was nominating Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court.

“During the confirmation hearings, I continuously asked myself questions in my mind like, ‘What can I show that’s different? How can I convey the feeling of this moment – and what it means to the Black community?’” says Maney. “Toward the end of the hearing, when I was running out of new ideas and angles to see from, I looked up and noticed Leila [Jackson]’s smile. It stunned me to the point where I didn’t take a photo right away because it made me pause and process what she must have been feeling. The pride. The joy. The hope for her own future. As a photographer, I always try to rely on my instinctive feelings to guide me.”

Not long after the image was taken, it was shared widely on social media. “Although I had no way of knowing how many people would relate to the image,” says Maney, “I’m grateful people could see themselves represented. I’m grateful that this image served as a symbol of why it’s important to have women of color and Black photographers documenting history. For so long, we have been denied the opportunity to document our own experiences. Although we still face those challenges, I hope others can continue to see why our voices are very much needed.”

Local children and their parents react to a makeshift memorial in downtown Uvalde, nearby Robb Elementary School, on May 26.

David Butow—Redux

‘Very, Very Raw and Painful to Watch’

On May 24, 19 students and two teachers were killed at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas. The next day, as the nation attempted to understand yet another tragedy, photographer David Butow traveled from his home in Los Angeles to document the aftermath. “I spent most of my childhood in Texas,” says Butow. “I have affection for the place, but in recent years have watched with dismay how the state government has trumpeted an aggressive pro-gun attitude, and I felt that made this event particularly tragic and ironic.”

Residents and media gathered at a local park in close proximity to the school. Butow found himself there along with a group of children and parents visiting the makeshift memorials. “I looked around my camera’s viewfinder at all those faces going through various expressions of pain and grief,” he says. “It was very, very raw and painful to watch, but it was real and it was happening right in front of me so I stayed in place for a few minutes taking dozens of pictures.”

Butow says he has mixed feelings about recording these children’s emotions in such a direct way, but he believes it is critical for the public to see the impact of the shooting. “It makes me sad and angry that Uvalde’s children suffered because of the selfishness and failures of many adults in this country who should be looking after them.”

Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, center, falls on the ground after being shot in Nara, western Japan, on July 8.

Kyodo/AP

Capturing a Moment in History

Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was shot from behind at close range on July 8 while giving a speech in the city of Nara in western Japan, where he was campaigning for the governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) ahead of legislative elections. His death at the age of 67 sent shockwaves around the world and stunned the nation, where gun violence is rare. Japan’s longest-serving prime minister, who had stepped down in 2020 owing to poor health, remained highly influential in Japanese politics until the end. The suspect, who used a handmade weapon in the brazen daylight attack, later said that he held a grudge against the South Korea-based Unification Church, which he blamed for bankrupting his family. An investigation following Abe’s murder uncovered widespread ties between the controversial religious group and the ruling LDP.

Although the photographer’s name is not public, this image is likely to be talked about and studied for decades. The composition of the image, which shows Abe’s face as well as the reactions of those around him, is remarkable, but the photographer’s ability to react and capture this moment of history is equally astonishing. – Amy Gunia

A Ukrainian soldier helps Julia Pavliuk and her daughter Emma evacuate the Kyiv suburb of Irpin, Ukraine, which Russian forces have tried to seize as part of their push to encircle the capital on March 5.

Maxim Dondyuk

‘My Own Emotions Echoed the Ones Depicted in My Photograph’

This photograph was taken by Ukrainian photographer Maxim Dondyuk in the city of Irpin, which had been under constant attack by Russians for several weeks. A bridge had been intentionally blown up so that the Russian tanks would not cross, leaving Ukrainians to flee across the broken remains by foot. Yet for many, it was safer to evacuate under the threat of shelling than stay behind.

Hundreds of frightened people were standing under the bridge, waiting to cross while their city burned in the background. “It all happened so fast,” Dondyuk says, “but I saw a terrified woman and a determined soldier carrying her crying child — and as a natural reflex, I made some images. Afterwards, I realized that my own emotions echoed the ones depicted in my photograph: courage, fear, helplessness, and care. I felt all these conflicting feelings at the same time.”

The next day Dondyuk returned to the bridge, and things were even worse. The Russians were firing directly at civilians. Dondyuk recalls, “Screams, tears, hysteria, loss of consciousness. Unfortunately, not everyone was as lucky as the woman and baby in my photograph. Many did not make it across, their bodies were left lying on the cold asphalt. Images of World War II emerged, scenes we thought would never be repeated.”

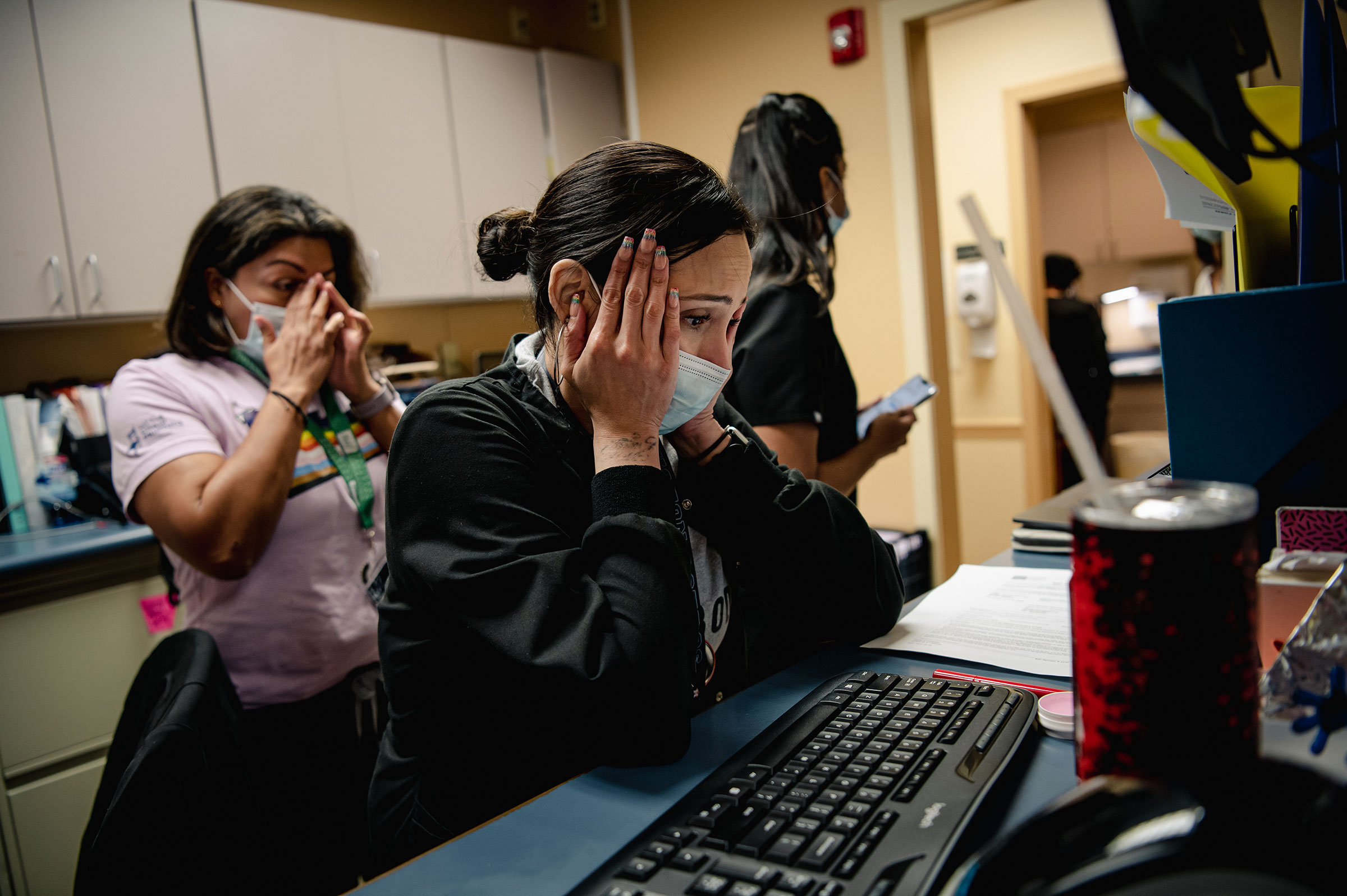

Nina, (center) and Priscilla (left), staff members of the Houston Women’s Clinic, the largest abortion provider in the city, react immediately after learning of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, and reverse American women’s constitutional right to an abortion, on June 24.

Meridith Kohut for The New Yorker

‘From the Perspective of the People Most Affected’

On June 24 the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, reversing the constitutional right to an abortion. Photojournalist Meridith Kohut was on assignment for the New Yorker, embedded inside the Houston Women’s Clinic, in the moments everything changed. Working alongside writer Stephania Taladrid, who secured rare access to the clinic, Kohut spent several days with the workers as they waited for the decision, knowing that if the landmark case was overturned, they would have to cease all abortion services immediately.

“As a photojournalist, I strive to cover news stories from the perspective of the people most affected…from the frontline,” says Kohut. “It is incredibly somber, sensitive work to bear witness to women making the profoundly difficult and personal decision to terminate their pregnancy. We understood the historic significance of the day, and the responsibility to document their experience.”

Kohut describes how Nina Revillas, the woman at the center of this photograph, “held a ritual with the director of the clinic – they would prop up Nina’s cell phone and watch the SCOTUS live blog on days when decisions were announced.” This image was captured in the seconds after the ruling came out. Three weeks later the clinic was closed and staff was laid off.

“I spent over a decade living in Caracas, Venezuela, documenting the lives of oppressed women who are denied reproductive freedom in countries across the Global South,” Kohut explains. “I thought a lot about them while working on this story, and the experience has deepened my sense of moral responsibility to continue documenting the plight of American women whose reproductive rights have been taken away.”

One of the first images from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope showing galaxy cluster SMACS 0723.

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Webb ERO

A Look Inside Our Universe

The James Webb Space Telescope took 25 years and $10 billion to design and build—and when it began returning its first album of eye-popping pictures in July, it proved to be worth every year and nickel spent. Webb’s cameras see not in optical light, but in the infrared spectrum, which gives them the capacity to look deeper into space and further into the past than any telescope ever built—13.6 billion light-years distant, which means they are seeing the universe in its infancy, as it existed just 200 million years after the Big Bang. This image of the galactic cluster known as SMACS 0723 contains thousands of galaxies, some of which are as far away as 13.1 billion light-years. (A single light-year is just under 6 trillion miles.) The bluer galaxies are more mature ones, containing many stars and little dust. The redder galaxies contain more dust, from which stars are still forming. The Webb is expected to have at least 20 years of usable life ahead of it, which means a wealth of other pictures, and a wealth of fresh knowledge. If the telescope does not kick the doors open to the origin of the universe, it will at least part the curtain wider than it’s ever been before. – Jeff Kluger

Ukrainian soldiers attend to a group of civilians, including Tetiana Perebyinis and her two children, who were mortally wounded by a Russian mortar round while they evacuated from Irpin, Ukraine, on March 6. A volunteer assisting the family was also killed.

Lynsey Addario—Getty Images

‘My Job is to Be Present, to Focus, and to Document’

In early March, less than a month after the fighting began between Russia and Ukraine, photojournalist Lynsey Addario was in Irpin documenting civilians as they fled across a destroyed bridge toward Kyiv. “The bridge had been well-documented by journalists in the previous days, and as it was a known civilian evacuation route, I assumed it would be relatively safe to cover. I went early on a Sunday morning, and shortly after arriving Russian forces positioned on the other side of the bridge started shelling the area around it.”

As Addario began to realize that Russian forces were targeting civilians, a sudden flash and explosion hit the asphalt between her, colleague Andriy Dubchak, security advisor Steve Bungay, and the line of fleeing civilians. Between struggling to see the aftermath through a cloud of dust, and trying to find out if she was bleeding, Addario eventually made her way across the street where she encountered the bodies of four people, one being a child. “I thought of my two sons and steeled my emotions,” she says. “I wanted to cry, and to flee, but reminded myself I had just witnessed the intentional targeting of civilians, and that I had to make some photographs to document the tragic scene.” The image was later used on the New York Times front page, and received a tremendous amount of attention.

“I’ve been covering war for over two decades,” says Addario, “and there were many times early on in my career where I had close calls and was in very dangerous situations. Times when I actually forgot to take photographs, or didn’t get close enough because I was too preoccupied with getting cover and protecting my own life. I’ve since learned that no matter how shaken up I am, if I can manage to pull myself together and get access to something, my job is to be present, to focus, and to document.”

More Must-Reads From TIME