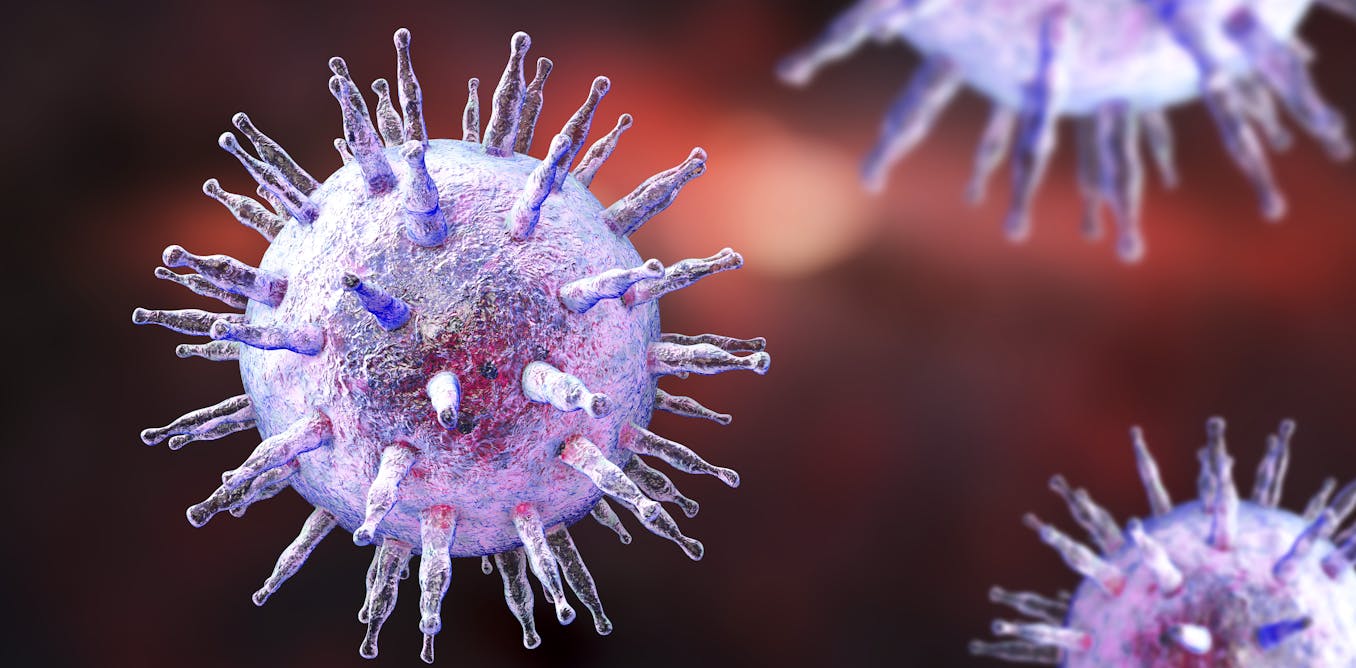

Over 95% of the world’s adult population is infected with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), but most people never realise it. The infection often causes few symptoms and then stays in the body for life.

But for a small minority, EBV is linked to serious disease. For more than 50 years, EBV has been recognised as the first virus shown to contribute to certain cancers, and is therefore classified as a group one carcinogen.

More recently, strong evidence suggests it plays a key role in the development of multiple sclerosis (MS), a disease in which the immune system attacks the brain and spinal cord. MS affects millions of people worldwide and is often diagnosed in early adulthood, with symptoms that can vary unpredictably over time.

I was part of a research team who explored how EBV infection may help initiate MS. Our findings suggest the disease could potentially be targeted by blocking the brain inflammation associated with EBV infection.

Using lab mice with a human-like immune system, we found that after infection, B cells (immune cells that produce antibodies and help coordinate immune responses) became unusually active and travelled into the brain. Here, they released signals that attracted T cells, which recognise and destroy infected or abnormal cells.

Together, these immune cells caused inflammation and early brain damage similar to what is believed to happen in the early stages of MS. When we used a commonly prescribed drug to remove the B cells, there were far fewer T cells in the brain and much less immune activation.

This suggests EBV may help set MS in motion by altering how B cells behave. These changed cells can enter the brain and drive inflammation, drawing in T cells that intensify the immune response. Targeting these B cells early could help prevent or slow the development of MS.

However, exactly how EBV contributes to MS is still being investigated.

MS affects the central nervous system, the brain and spinal cord. In people with MS, the immune system damages myelin, the protective coating around nerve fibres that helps electrical signals travel quickly. When it is stripped away, messages between the brain and body slow down or fail.

Over time, repeated damage can also affect the nerves themselves, leading to symptoms such as problems with movement, vision, balance and fatigue.

MS is an autoimmune disease. This means the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues. One leading explanation for how EBV fits into this process is a form of mistaken identity, where immune responses first directed at the virus begin to resemble those aimed at myelin by people who have MS.

Why doesn’t everyone develop MS?

If EBV infection is so common, why doesn’t everyone develop MS? Other factors shape risk, including genetics, sex, smoking, obesity and low vitamin D levels. EBV appears to be an important part of the puzzle, but it is unlikely to act alone.

EBV infects B cells, the immune cells that produce antibodies, and can remain dormant inside them for life. But in some situations, the virus can reactivate. EBV-infected cells have been linked to certain cancers when immune control fails.

New research is beginning to reveal what this looks like inside the nervous system. A recent study found unusually high numbers of EBV-targeting immune cells in the cerebrospinal fluid, which surrounds the brain and spinal cord, of people with MS. Many were T cells primed to recognise the virus, suggesting the immune system may be responding to EBV activity within the central nervous system.

When immune cells gather there, they can spark inflammation. This allows more immune cells to enter the brain and spinal cord and cause local damage, forming patches known as lesions that underpin many symptoms of MS.

Treatments and the role of B cells

Current treatments mostly work by calming the immune system rather than targeting a single cause. Many of these medicines are immunosuppressants, which can increase infection risk but also reduce relapses and slow disease progression.

One of the most effective MS treatments targets B cells using monoclonal antibody drugs, laboratory-made proteins designed to recognise specific immune cells. Examples include ocrelizumab, rituximab and ofatumumab. These therapies reduce B cell numbers and may also lower the pool of EBV-infected cells.

These treatments have improved outcomes for many patients. But by dampening part of the immune system, they can also increase infection risk and reduce vaccine responses.

This raises an obvious question: could preventing EBV infection stop MS developing in the first place? And if so, why not prevent EBV infection with a vaccine?

Developing EBV vaccines has proved difficult, partly because the virus hides inside cells and establishes lifelong infection. Researchers are exploring this area, and none are currently approved. It remains unclear whether preventing EBV infection would reduce MS risk.

The link between EBV and MS is now one of the most active areas in MS research, and is reshaping how prevention and treatment are being explored.

Rather than viewing MS solely as an immune system disorder, researchers are increasingly investigating whether stopping EBV infection, or targeting cells that harbour the virus, could reduce a person’s risk of developing the disease or slow its progression.

This shift is driving new strategies, including therapies aimed at EBV-infected B cells, and efforts to design vaccines or immune-based treatments that interrupt the biological processes connecting the virus to MS. If successful, these approaches could move MS care beyond symptom control, towards prevention or earlier disease-modifying interventions.

![]()

Eanna Fennell receives funding from the Irish Research Council and Horizon Europe.