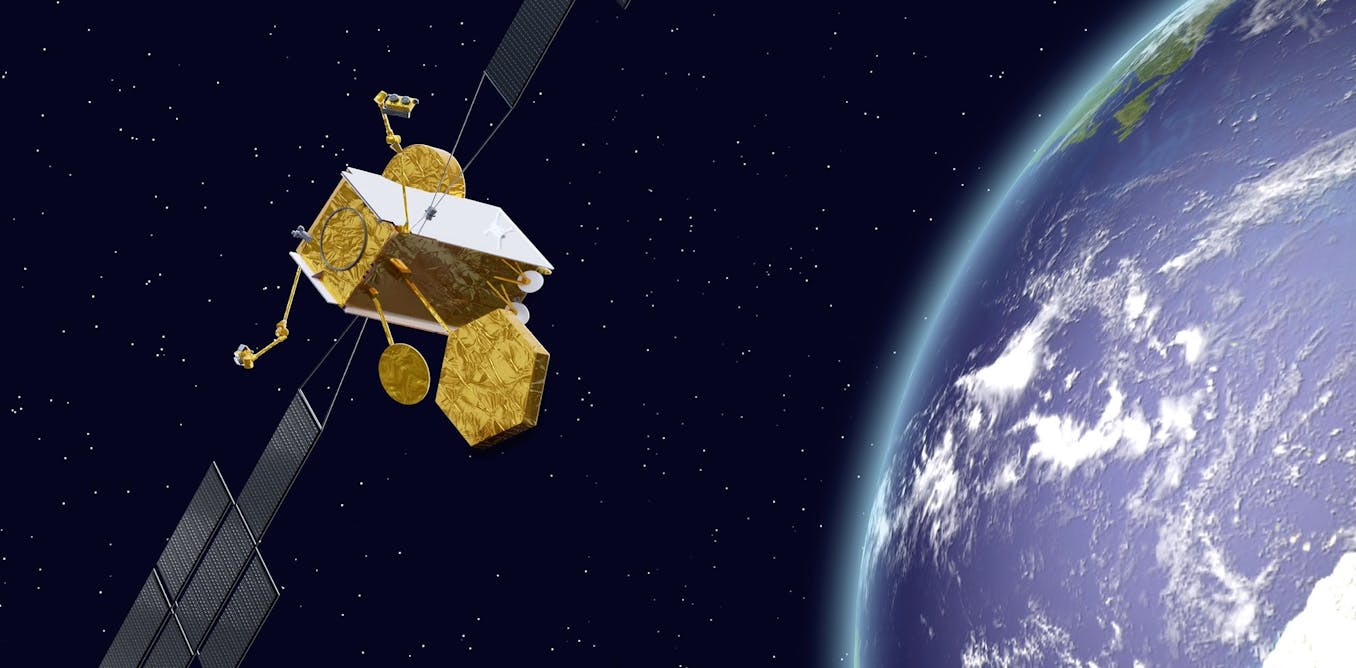

Russia is targeting UK space infrastructure, and in particular military satellites, on a weekly basis, according to the head of UK Space Command.

In an interview with the BBC, Maj Gen Paul Tedman said that Russia was “shadowing” UK satellites. Shadowing involves orbiting and aligning a satellite close to the target satellite, in order to be near enough to jam communications or intercept signals to steal critical information.

Tedman said Russia’s satellites had “payloads on board that can see our satellites and are trying to collect information from them”. He also confirmed that jamming of UK military satellites was taking place.

This involves broadcasting signals on the same frequencies as those used by satellites, in order to intentionally disrupt or overwhelm legitimate signals. It does not physically damage spacecraft, so as soon as the jamming signal is no longer being emitted, communications can be restored. The jamming of satellite signals can take place from the ground, ocean or air, as well as from space.

But what about other tactics that could be used to disrupt satellites? One thing not mentioned in relation to the attacks on British military satellites, is the use of lasers. These can be deployed to dazzle satellites’ onboard optical sensors. This can interfere with electronic circuity but would not cause lasting physical damage.

The most serious type of attack of course would be the use of a direct-ascent missile, which can be launched from the ground, sea or air, to destroy an orbiting satellite. Previous tests of this kind of anti-satellite (Asat) weapon have generated worrying levels of orbiting debris. This debris can then collide with other satellites, potentially generating even more debris for other space-based assets to avoid.

On February 24, 2022, the day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, satellite broadband users across Europe got a taste of the kind of attacks that the military is now used to. A cyber-attack was launched against Viasat’s Ka-Sat satellite network, which supplies internet access to tens of thousands of people across Ukraine and the rest of Europe. Experts said they believed the purpose of the attack was to interrupt service rather than to access data or systems.

A recent talk by German IT researchers also revealed how much damage hackers could potentially do if given unfettered access to a satellite’s onboard systems. The experts said that attackers could exploit vulnerabilities in open source software used by Nasa and Airbus to control satellites. This in turn could give the intruders access to the control functions on a satellite, allowing them to change its orbit by sending a command to fire its thrusters.

Attacks don’t need to target the satellite directly. Targeting control stations on the ground can also disrupt operation of the satellites in orbit. This can also have consequences for end users of a satellite service.

Wider problem

It’s not just the UK’s satellites that are being targeted, however. In September, the head of French space command Maj Gen Vincent Chusseau said there had been a spike in hostile activity in space. Chusseau said activity had increased since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

He said that adversaries, especially Russia, have diversified methods of disrupting satellites and that jamming, lasers and cyber-attacks have become commonplace.

Christopher DeWitt, Space Command

The same month, Brig Gen Christopher Horner, commander of 3 Canadian Space Division told a space security summit that there were more than 200 anti-satellite weapons orbiting Earth.

While he didn’t provide details on their nature, he said it was a “shocking number” to threaten allied satellites.

Increased investment

It’s possible to satellites by improving the encryption of data transmitted to them as well as with anti-jamming technology. This uses a variety of techniques to block out or nullify the signals used by jammers to interfere with satellite communications. It’s also important to ensure there are alternative providers for critical space services as a backup in case of attack.

In response to increasing threats to UK satellite infrastructure, the UK government has recently increased its investment in projects geared towards space security. The government has invested £500,000 in a project to develop sensors that counter lasers used to blind satellites. The UK has also recently developed Borealis, a software platform designed to monitor and protect critical UK and allied satellites.

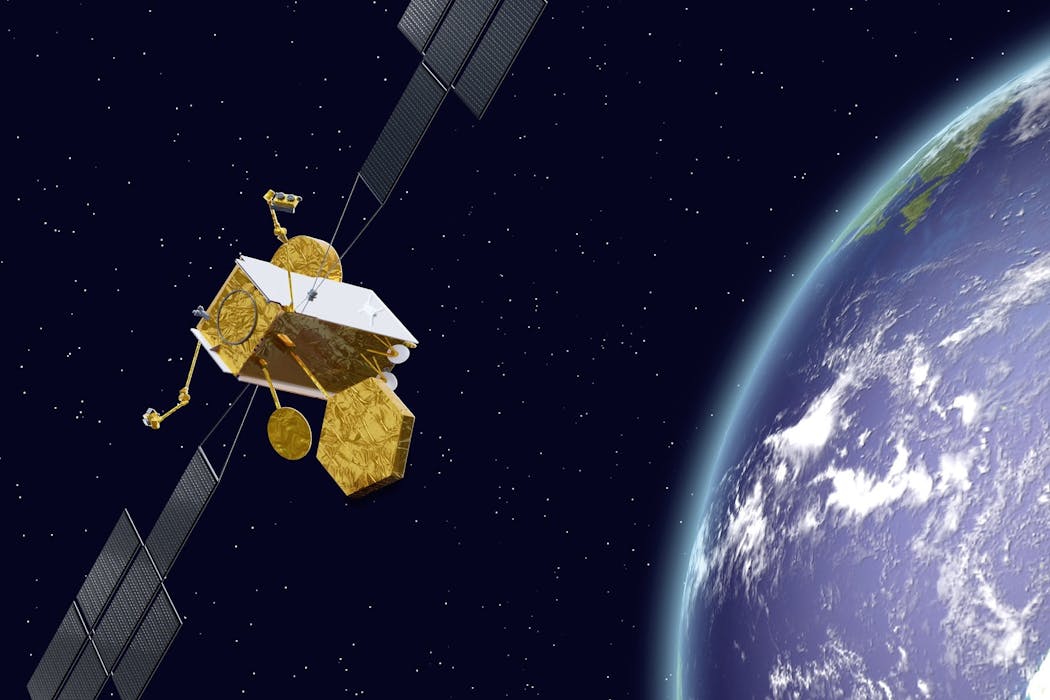

As well as investing in its own projects, the UK has also sought to improve space-based security by strengthening international partnerships. For instance, the UK recently invested €163 million (£141 million) in Eutelsat, which provides satellite internet and is a rival to Elon Musk’s Starlink system.

Starlink’s importance not only for consumers, but also for military applications has been demonstrated in the Ukraine war – where Ukrainian troops had come to rely heavily on it for battlefield communications. But the drawback to this dependency on a privately owned company such as Starlink was highlighted when Musk denied coverage to Kyiv in 2023.

The investment in Eutelsat not only strengthens space-based collaboration between the UK and France, but also boosts a company providing a backup system for satellite communications.

The US and UK also recently conducted their first coordinated satellite manoeuvre. The US repositioned one of its own satellites to examine a UK satellite to make sure it was operating normally. Such a manoeuvre could potentially be used following an attack designed to disable a spacecraft.

The reports of Russian meddling highlight the importance of security in orbit as global tensions continue to expand into space.

![]()

Jessie Hamill-Stewart does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.