US president Donald Trump is surrounded by a new cohort of politicians and officials. While one of his campaign promises was to overthrow the “corrupt elites” he accuses of flooding the American political arena, his second term in office has elevated elites chosen, above all, for their political loyalty to him.

The media’s focus on Trump’s comments on making Canada the 51st US state and annexing Greenland and billionaire Elon Musk’s support for some far-right parties in Europe has obscured the ambitious programme to transform the federal government that the new political elite intends to implement.

In the wake of Trump’s inauguration on January 20, the Republican elites most loyal to the MAGA (“Make America Great Again”) leader, who staunchly oppose Democratic elites and their policies, are operating amid their party’s control over the executive and legislative branches (at least until the midterm elections in 2026), a conservative-dominated Supreme Court that includes three Trump-appointed justices, and a federal judiciary that shifted right during his first term.

However, the political project of the Trumpist camp consists less of challenging elitism in general than attacking a specific elite: one particular to liberal democracies.

Castigating democratic elitism

Typical anti-elite political propaganda, along the lines of “I speak for you, the people, against the elites who betray and deceive you,” claims that a populist leader would be able to exercise power for and on behalf of the people without the mediation of an elite disconnected from their needs.

Political theorist John Higley sees behind this form of anti-elite discourse an association between so-called “forceful leaders” and “leonine elites” (who take advantage of the former and their political success): a phenomenon that threatens the future of Western democracies.

Since the Second World War, there has been a consensus in US politics on the idea of democratic elitism. According to this principle, elitist mediation is inevitable in mass democracies and must be based on two criteria: respect for the results of elections (which must be free and competitive); and the relative autonomy of political institutions.

The challenge to this consensus has been growing since the 1990s with the increased polarization of American politics. It gained new momentum during and after the 2016 presidential campaign, which was marked by anti-elite rhetoric from both Republicans and Democrats (such as senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren). At the heart of some of their diatribes was an aversion to “the Establishment” on the east and west coasts of the United States, where many prestigious financial, political and academic institutions are based, and the conspiracy notion of the “deep state”.

The re-election of Trump, who has never admitted defeat in the 2020 presidential vote, growing political hostility and the direct involvement of tech tycoons in political communication –especially on the Republican side– further reinforce the denial of democratic elitism.

Trump’s populism from above: a revolt of the elites

The idea that democracy could be betrayed by “the revolt of the elites”, put forward by the US historian Christopher Lasch (1932-1994), is not new. For the anthropologist Arjun Appadurai, it is a particular feature of contemporary populism, which comes “from above.” Indeed, if the 20th century was the era of the “revolt of the masses”, the 21st century, according to Appadurai, “is characterized by the ‘revolt of the elites’.” This would explain the rise of populist autocracies (such as those currently led by Viktor Orban in Hungary, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey and Narendra Modi in India, and formerly led by Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil), but also the election successes of populist leaders in consolidated democracies (including those of Trump in the US, Giorgia Meloni in Italy, and Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, for example).

As Appadurai explains, the success of Trumpian populism, which represents a revolt by ordinary Americans against the elites, casts a veil over the fact that, following Trump’s victory in November, “it is a new elite that has ousted from power the despised Democratic elite that had occupied the White House for nearly four years.”

The aim of this “alter elite” is to replace the “regular” Democrat elites, but also the moderate Republicans, by deeply discrediting their values (such as liberalism and so-called “wokeism”) and their supposedly corrupt political practices. As a result, this populism “from above” carried out by the President’s supporters constitutes an alternative elite configuration, the effects of which on American democratic life could be more significant than those observed during Trump’s first term.

Beyond the idea of a ‘Muskoligarchy’

The idea that we are witnessing the formation of a “Muskoligarchy” –in other words, an economic elite (including tech barons such as Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg and Marc Andreessen) rallying around the figurehead of Elon Musk, whom Trump asked to lead what the president has called a “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) –is seductive. It perfectly combines the vision of an alliance between a “conspiratorial, coherent, conscious” ruling class and an oligarchy made up of the “ultra-rich”. For the Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf, it is even a sign of the development of “pluto-populism”. (It is also worth noting that former president Joe Biden, in his farewell speech, referred to “an oligarchy… of extreme wealth” and “the potential rise of a tech-industrial complex.”)

However, some observers are cautious about the advent of a “Muskoligarchy.” They point to the sociological eclecticism of the new Trumpian elite, whose facade of unity is held together above all by a political loyalty, for the time being unfailing, to the MAGA leader. The fact remains, however, that the various factions of this new “anti-elite” elite are converging around a common agenda: to rid the federal government of the supposed stranglehold of Democratic “insiders.”

An ‘anti-elite’ elite against the ‘deep state’

In his presidential inauguration speech in 1981, Ronald Reagan said: “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” The anti-elitism of the Trump elite is inspired by this diagnosis, and defends a simple political programme: rid democracy of the “deep state.”

Although the idea that the US is “beleaguered” by an “unelected and unaccountable elite” and “insiders” who subvert the general interest has been shown to be unfounded, it is nonetheless predominant in the new Trump Administration.

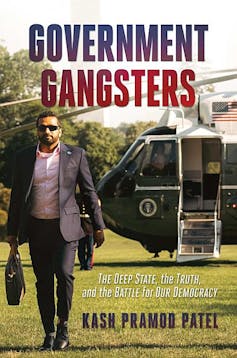

This conspiracy theory has been taken to the extreme by Kash Patel, the candidate being considered to head the FBI. In his book, Government Gangsters, a veritable manifesto against the federal administration, the former lawyer writes about the need to resort to “purges” in order to bring elite Democrats to justice. He lists around 60 people, including Biden, ex-secretary of state Hillary Clinton and ex-vice president Kamala Harris.

Google Books

The appointment of Russell Vought as head of the Office of Management and Budget at the White House, a person who is known for having sought to obstruct the transition to the Biden Administration in 2021, also highlights the hard turn that the Trump administration is likely to take.

Reshaping the state around political loyalty

To “deconstruct the administrative state”, the “anti-elite” elites are relying on Project 2025, a 900-plus page programme report that the conservative think-tank The Heritage Foundation, which published it, says was produced by “more than 400 scholars and policy experts.” According to former Project 2025 director Paul Dans, “never before has the entire movement… banded together to construct a comprehensive plan” for this purpose. On this basis, the “anti-elite” elite want to impose loyalty to Project 2025 on federal civil servants.

But this idea is not new. At the end of his first term, Trump issued an executive order facilitating the dismissal of statutory federal civil servants occupying “policy-related positions” and considered to be “disloyal”. The decree was rescinded by president Biden, but Trump on his first day back in office signed an executive order that seeks to void Biden’s rescindment. As President, Trump is also able to allocate senior positions within the federal administration to his supporters.

The “anti-elite” elite not only want to reduce the size of the state, as was the case under Reagan’s “neoliberalism”, but to deconstruct and rebuild it in their own image. Their real aim is a more lasting victory: the transformation of democratic elitism into populist elitism.