Homer’s Iliad is so canonical in world literature that even without having read the epic, most people are familiar with the broad scenario of the Trojan war, triggered by the Trojan prince Paris’s abduction of the Greek beauty Helen, “the face that launched a thousand ships”.

However, the Iliad is hardly a romance. The abduction scene is only alluded to in the poem. The major theme is war, with the conflict approaching its tenth year.

The Iliad is a poem of violence, with many of the scores of deaths described in excruciating detail. But the fight is not only against the human foe. There is also the battle to protect nature, as Homeric heroes take on the role of eco-warriors in a physical environment threatened by human activity.

There is an acute consciousness of the natural world in the Iliad, of its flux and fragility. Indeed, a significant barrier to identifying Homer’s Troy with the remains of the ancient city of Troy located in modern northwestern Turkey is the fact that the landscape has changed so much over the three millennia since the historical event the Iliad is, arguably, based on.

This article is part of Rethinking the Classics. The stories in this series offer insightful new ways to think about and interpret classic books and artworks. This is the canon – with a twist.

Of course, war means massive destruction to the environment, as illustrated by the deep trench the Greeks dig to defend their ships – an encroachment which provokes the gods. There is also unnatural disasters to contend with, such as strikes from Zeus’ thunderbolts.

The actual conflict is described as both flood and wildfire. In this context, Homeric heroes must get nature on their side if they are to overcome the enemy.

As Homer rarely comments directly on the narrative, similes (literary devices that show similarity between different people or things) often do the work of depicting the environmental forces. In particular, similes involving the weather are more frequent than meteorological phenomena actually experienced by the characters.

In one scene about the ferocity of his attack, chief Trojan hero Hector is compared to a wave smashing into a floundering ship and a lion pouncing on cattle.

Wiki Commons, CC BY-SA

This dual image, combining the inanimate (the wave) and animate (the lion) worlds represents the revenge of warrior and nature. Revenge is a recurring motif in the Iliad as a response to an affront. However, Hector’s revenge on the Greek invaders is compromised because it is preordained that he will be killed and Troy taken. Nature’s revenge is justified by the human devastation of the environment.

The lion is a frequent simile in Homer and particularly apt because the European lion population had been ravaged during the classical period. So Hector’s revenge is more complete when he is viewed through this imagery as an instrument of nature, contrasting human mortality with the boundlessness of the natural world.

Achilles’ battle against the river

In an extraordinary episode featuring the Iliad’s central hero Achilles, Homer uses direct narrative to position the eco-warrior.

For much of the Iliad, Achilles is effectively on strike, peeved by the confiscation of his enslaved girl, Briseis. When he does return to action, he too is motivated by revenge because Hector has killed his friend Patroclus.

Achilles carries the onslaught into the river Scamander, which becomes glutted with corpses. The Scamander is also a god and objects to the violation, but Achilles continues in his frenzy.

Emily Wilson, author of an acclaimed recent translation of the Iliad, reads this as “a human fighting the landscape”. Yet, by bringing the slaughter to the river, Achilles is showcasing the impact of the war on the environment and nature’s ultimate superiority.

Louvre Museum

The mortal enemy cannot stop Achilles, but Scamander swamps him and he has to be bailed out by allied gods. Almost drowned by the angry river, a bedraggled Achilles trudges through fields disfigured by corpses and discarded armour, and recognises that the forces of nature are inviolable so should remain unviolated.

Spanning days rather than years, the drama of the Iliad is but a snapshot of the Trojan war. Yet, this very transience suggests the nature of the conflict – the conflict with nature.

To be a hero means to find kleos (fame), which is prized because it transcends the oblivion of time. Human life cannot be renewed, so it should be valued. This finiteness applies even to the seemingly limitless resources of nature.

Homeric eco-warriors are not represented as taking environmental action in the modern sense – there was no environmental discourse in Greek. Instead, the narrative reflects their precarious place in a delicate natural world. For heroes to survive, nature must thrive.

Beyond the canon

As part of the Rethinking the Classics series, we’re asking our experts to recommend a book or artwork that tackles similar themes to the canonical work in question, but isn’t (yet) considered a classic itself. Here is Wayne Mark Rimmer’s suggestion:

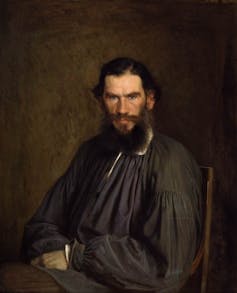

Less celebrated than War and Peace is Leo Tolstoy’s novel Resurrection (1899), the story of aristocrat Nekhlyudov’s social-political reawakening.

Tretyakov Gallery

Written six years before the first Russian revolution, Resurrection carries a strong evangelical message. It is also a commentary on the environment, specifically, how social class changes perceptions towards the land.

The peasants in their poverty have a pragmatic attitude, evaluating land in terms of yield and exploitation, as illustrated by a husband jailed for illicit logging. In contrast, Nekhlyudov has a strong appreciation of the land’s physical beauty and a sense of affinity that comes through ownership.

Nekhlyudov’s surrender of his land to the peasants meets with their incredulity, as does his statement: “The earth is no man’s.” Left unanswered is how the peasants perceive the land as its masters. Tolstoy, a land owner himself, lived neither to see the 1917 Russian revolution nor Stalin’s collectivisation programme, which desolated the countryside.