Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) was one of the most famous figures of his time, not only in his native Prussia but throughout the world. In addition to being a leading geographer, climatologist, ecologist and oceanographer, he attached great importance to the dissemination of knowledge to society as a whole.

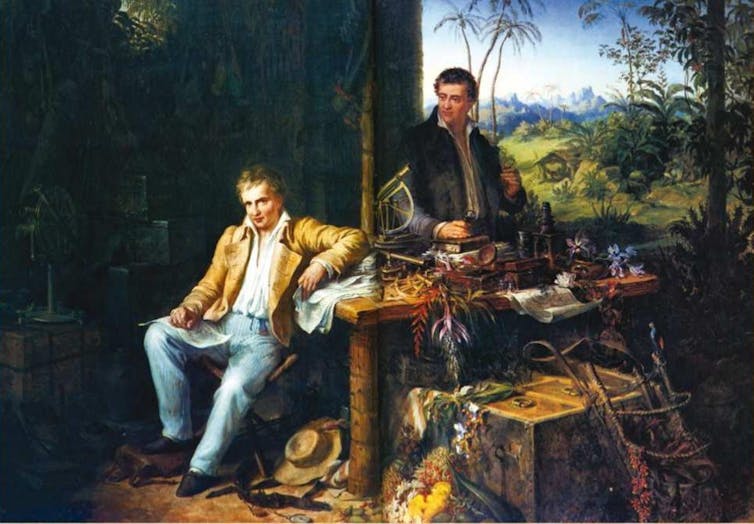

Wikimedia commons

He devoted much of his life to lecturing and publishing books and articles, with a single-minded commitment that would eventually led him to financial ruin. Humboldt is one of the ten masters whose lives and works I recount in my recent book Grandes comunicadores de la ciencia. De Galileo a Rodríguez de la Fuente (Great Scientific Communicators: From Galileo to Rodrigez de la Fuente), edited by Comares and Fundación Lilly and released this year.

A life of adventure

In 1799 Humboldt requested permission from King Charles IV of Spain to explore the Spanish colonies in America. Against all odds, the monarch authorised the trip, apparently impressed by the young man’s knowledge and the arsenal of scientific instruments at his disposal.

Before embarking for America, Humboldt travelled through Spain, taking measurements that proved the Iberian Peninsula is essentially a plateau. During his travels he aroused the suspicions of local villagers, who thought he was worshipping the moon when he made his nocturnal observations.

Humboldt University of Berlin, CC BY

His voyage left the port of A Coruña and took him, together with the French botanist Aimé Bonpland, through lands that today belong to Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Mexico, Cuba and the United States. It was a true adventure, full of such dangers as a jaguar attack, a rough journey along the Orinoco River that almost ended in shipwreck, and a collapsing ice wall during the ascent of a volcano in the Andes.

He also unsuccessfully attempted to summit Chimborazo, but did manage to set a new record by reaching an altitude of 5,610 metres, the highest point known to be reached by a human at the time.

A pioneering environmentalist

The expedition served to collect scientific data on plants, animals, minerals and climate. Around 60,000 plant species were identified, of which about 1,500 were new to science.

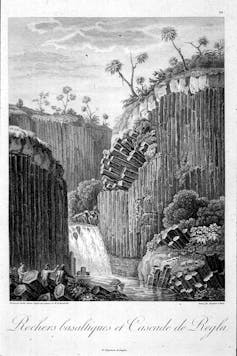

Wikimedia commons, CC BY

Humboldt was an early proponent of ecology, conceiving the universe as a system in which everything is interconnected, and was also the first to highlight the effects of human action on the climate. Analysing the changes in Lake Valencia (in modern-day Venezuela), he deduced that when forests were destroyed to make way for farmland, springs and rivers dried up. He also noted that every time heavy rains fell on mountain peaks, the rainwater formed channels that washed away loose soil, causing floods.

A self-funded author

Wikimedia commons

After his voyage, Humboldt returned to Europe and devoted himself to sharing his findings. He published 32 volumes of his Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America between 1814 and 1831. He subsequently published five volumes of his magnum opus, Cosmos, between 1845 and 1848, which aimed to be a compendium of all existing knowledge of natural science at the time.

Many of these books were printed in large folios, containing more than 1,400 sumptuous artworks by the best illustrators of the time. In their original edition, some of these volumes were so heavy that two people were needed to carry them. These costly publications were paid for by Humboldt himself, eventually leading him to bankruptcy.

Reaching the widest possible audience

In addition to books, Humboldt’s interest in democratising science led him to use all platforms available to him.

He published around 750 articles in the most important newspapers and magazines of his time, including the German paper Allgemeine Zeitung, The Economist, The Times, The New York Times and the Caracas-based Diario de Avisos, among many others.

Humboldt was also a gifted speaker. He gave 78 lectures based on his Cosmos writings that, for a time, became the social event of the moment in Berlin. His democratising spirit led him to open them up to anyone who was interested, including women, who at that time were barred from accessing universities.

Humboldt himself paid to rent and heat the large hall where these lectures were held, which could accommodate over 1,000 people.

His entire oeuvre has an extraordinary literary quality. In his travel diaries he makes it clear that science and poetry are not opposites, but that they can, in fact, complement one another:

“Descriptions of nature, I repeat here, can be sharply defined and scientifically precise without being deprived of the invigorating touch of imagination. The poetic must emerge from the sensed connection between the sensual and the intellectual, from the feeling of universal distribution, of mutual limitation and the unity of nature.”

Whether through written or spoken language, Humboldt was able to captivate the public, which helped him to increase his popularity and, as a consequence, his influence as a scientist. His life and work demonstrated the importance of public communication in sharing scientific knowledge.