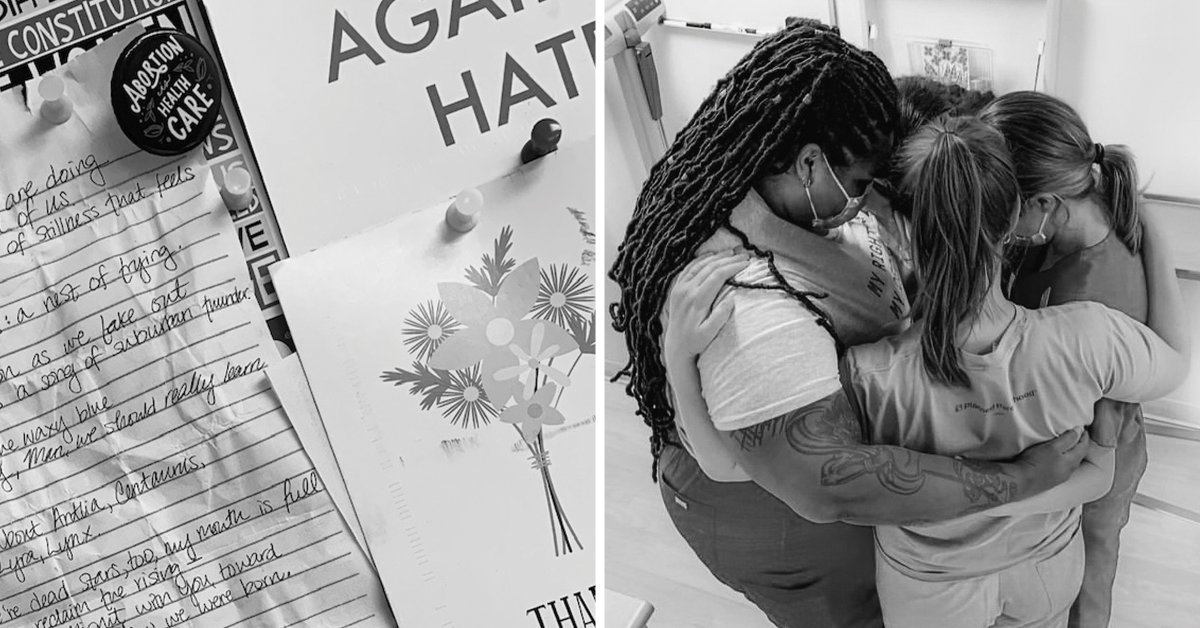

A piece of line-ruled notebook paper, tattered and torn, has been with me–first folded and carried in my medicine bag, then pinned onto a bulletin board at work–since June 24, the day the Supreme Court handed down its decision in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health, overturning Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Handwritten and faded, amid the thank-you cards from patients and the Post-its with phone numbers for local hospitals, shelters, rape crisis centers, and domestic-violence hotlines, is Ada Limón’s poem “Dead Stars.”

In it, Limón asks:

We’ve come this far, survived this much. What

would happen if we decided to survive more? To love harder?

Grief is a long-familiar colleague of abortion-care workers in the U.S.–not because abortion is inherently tragic or traumatic, but because we spend our days and nights bearing intimate witness to the violence of our health care system, the intricacies of individual bodies and lives, the personal and sacred details of the circumstances surrounding if and when and how a person will become a parent, and the lived experiences of pregnant people in this country.

Five years ago, I applied for a job at a reproductive health care clinic. I loved supporting patients in a clinical setting, but as I began to learn from other care workers–in particular Black and Indigenous leaders of the reproductive justice movement, and those living and working in the South–about the ways in which much of this country was effectively “post-Roe,” long before this summer’s ruling, I found myself coming up against the limitations of my position. Roe never protected many of us, and its disappearance only deepens the inequities of its protections. So I took on an additional role, that of an abortion doula. Working outside the hours of my day job and providing my services for free, I could show up for people near and far who needed support and resources to navigate our country’s broken health care system. I could partner with folks in my own communities to meet their physical, emotional, financial, logistical, and sometimes spiritual needs–the human needs that have existed and will exist with and without Roe.

Read More: More People Are Relying on Abortion Funds 6 Months After the Fall of Roe

The June 24 ruling was not so much a declaration of war as an escalation of the battles we’ve been fighting. Before Roe was overturned, many patients were already forced to travel hundreds or thousands of miles to access care or to wait weeks upon weeks for their appointment. Some might have chosen to continue their pregnancies, were it not for our country’s terrifying layers of risk: abysmal maternal and infant mortality rates, state violence against–and the policing and incarceration of–children and families, generational poverty, and a complete lack of social support systems. Doula clients held my hand or cried with me on the phone as they came up against the laws and restrictions designed to punish and shame them–unspeakably cruel fetal-burial mandates, traumatic and burdensome waiting periods and insurance denials, medically unnecessary ultrasounds. And all of this piled on top of someone’s complex and personal reproductive life, a foundation of all the experiences and emotions and desires and traumas and fears that their body must carry into a pregnancy to begin with.

The witnessing of, and often partaking in, the suffering caused by the Dobbs decision has added a new layer of trauma for the care workers who have always fought for our patients on the legal and medical front lines–those of us who have been in these trenches, together, before this particular battle was fought.

What if we stood up with our synapses and flesh and said, No.

No, to the rising tides.

On the day I copy the poem down, my handwriting rushed and sloppy, a nurse who works in Texas tells me about the patient in her clinic’s waiting room who, after being informed that her procedure is now, suddenly, illegal and that she must go home, still pregnant, clutches at the nurse’s arm, begging and pleading for help.

Read More: These Are the States That Voted to Protect Abortion Rights in the Midterms

Closures of clinics that, for many people, were the sole source of accessible reproductive health care. A 10-year-old rape victim forced to travel to another state in order to receive care. Debates between doctors and lawyers about what counts as “lifesaving” care, putting patients’ well-being at risk. The knowledge that abortion bans bring an escalation of criminalization and policing of pregnant people–disproportionately poor people, Black and Indigenous people and other people of color, and people who already have children to care for. Maternal and infant death rates, already staggering, rising in the states that ban abortion.

“Make sure you’re taking time for self-care, honey,” says a relative on the phone. I refill my wine glass.

I’m drinking more, sleeping less. One coworker tells me her doctor and therapist agree that she desperately needs to take a mental-health leave, but she cannot afford to do so on her $18.57 hourly wage; another colleague has doubled their workload, traveling to a neighboring state to help as many patients as they physically, logistically can. What can you say about “self-care,” about taking time to grieve, to people whose jobs entail running back into the burning building over and over again? What can you say about “taking time” to those trapped inside that building, calling for help?

I half-jokingly ask a coworker, as she washes speculums in the clinic’s industrial sink, how her mental health is these days. She laughs so hard that she starts crying.

The attacks on our work have played out, of course, against the backdrop of all of the other ordinary, mundane griefs in our lives. The elderly woman in the bathroom when I visit a doula client in a local hospital: hearing aids nestled among her clouds of white hair, a tremor in her frail and wrinkled hands, her fingers knotted and gnarled with arthritis and her back hunched as she bends to sweep bits of toilet paper off the tile in her janitor’s uniform. The clinic nurse who leaves work to drive around our city for nearly two hours in search of formula for her 7-month-old, each supermarket shelf bare of the one brand her baby can safely metabolize. The midwife whose young son waits anxiously for her at home, having refused to get on the bus to his summer camp because, he told her, he carries a certainty deep in his small bones that if he goes to camp, a guy with a gun will come. “To shoot all the kids, mama,” he said. “He’s going to come shoot us.”

Read More: The Reversal of Roe Sealed My Decision to Leave Texas

I make a routine phone call to someone with three young children; a baby cries in the background. I ask if she has any questions, if she wants to talk anything through or needs any resources or support before her upcoming abortion appointment. She asks, a ripple of fear in her voice: if her abusive boyfriend finds out that she’s pregnant and that she’s gone to see a doctor, will he be able to sue her? I assure her that S.B.8–the Texas law with an enforcement mechanism allowing private citizens to sue anyone they suspect of “aiding or abetting” an abortion–will have no bearing on the care she is seeking, thousands of miles away from Texas, but she remains unconvinced. He would, she says. He would sue me for everything, if he didn’t kill me first.

It’s not the first time someone has told me something like this, and it won’t be the last. Homicide is, after all, a leading cause of death for pregnant Americans. Patients often tell us of threatening or abusive partners and family members, who use interpersonal violence to exert the very same control over their bodies as Supreme Court justices, governors, pharmacists, pastors, and police. And as the anti-abortion movement fixes telehealth services, contraceptives, and even access to information about reproductive health care in their crosshairs, more and more of us are being robbed of the freedom to safely build our families and the power to create and direct our own lives.

Read More: An Alabama Clinic Reinvents Itself for a Post-Roe World

“If I wake up and fixate on the grief,” says Dr. Iman Alsaden, chief medical officer at Planned Parenthood Great Plains, which serves western Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, “it’s so heavy that it would be hard to keep going.” And to keep going, to plug up the holes in this dam with our freezing and exhausted fingers, is our calling. The more people who must travel to see us, who must endure the long waits at overburdened clinics, and the more suffering caused by anti-abortion legislation and harassment campaigns, the more work there is for us to do. “We’re not going anywhere, even in grief,” says Dr. Alsaden. “Grief can be a motivator.”

What would happen if we used our bodies to bargain

for the safety of others, wonders Limón from my bulletin board.

Time passes; we grieve the loss of Roe, and we remember those it left behind, and we move forward without it. One night in the fall, as we approach the six-month anniversary of the Dobbs ruling, I text Rupali Sharma, an attorney with the Lawyering Project. She has been working all night in a hotel, away from her own toddler and sleeping in short bursts between filing emergency briefs and fielding panicked communications from distraught abortion providers and independent clinics as yet another oppressive bill is introduced. We’ll keep fighting, I type. We’ll keep going.

A moment later, as I run a bath for my child, my phone lights up with her response.

Yes we will, she says. No choice but to.

More Must-Reads From TIME