Jorge Isla discusses his article: “Animal-mediated seed dispersal and the demo-genertic configuration across plant colonization gradients.”

Background

Significant changes in the landscape, such as rural abandonment or the protection of natural areas, are creating a new ecological context for the formation and regeneration of forested areas. The significance of mutualistic interactions between plants and animals in ecosystems is acknowledged, but we lack a comprehensive understanding of their role during the processes of colonization and expansion. An iconic plant-animal interaction is the dispersal of seeds by frugivorous animals. By feeding on fruits, these animals transport plant seeds to new locations, enabling the regeneration and expansion of natural populations. Depending on patterns in animal feeding and movement, the spatial pattern of seed dispersal (seed-rain) may originate from just a few or from many individual plants.

However, a threat is looming over these expanding plant populations. Rapid expansion in a species’ range can lead to a loss of diversity for natural populations. This is due to founder effects; when a small group of individuals become separated from the source population and found a new population. We thought that seed dispersal, mediated by frugivorous animals, could help to mitigate this loss of diversity. Exploring seed-rain patterns from a maternal perspective will help us to understand the role of plant-animal interactions in determining the composition and diversity of future forests.

The study

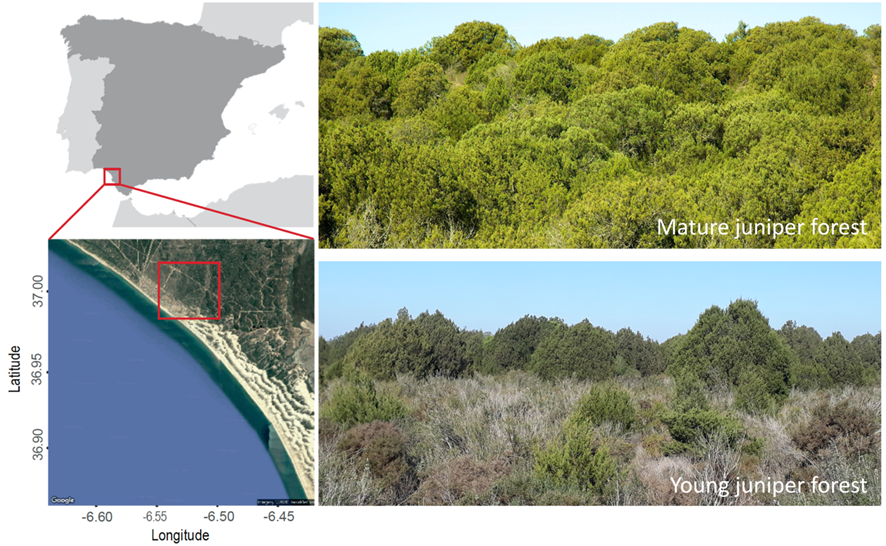

We focused on a population expansion gradient of a type of juniper, Juniperus phoenicea, in the Doñana Biological Reserve (Spain).

Over two years, we sampled the seed rain in three stands along this expansion gradient. Additionally, we were aware that frugivore-generated seed rain can be structured based on the microhabitats that animals choose or avoid for feeding, perching, or protection. For this reason, we sampled seed rain under five different microhabitats: pine trees, Juniper trees, fleshy-fruited shrubs, dry-fruited shrubs, and open area soils. The sampling was conducted in three stands across the maturity gradient: mature stand, intermediate-maturity stand, and colonization front stand.

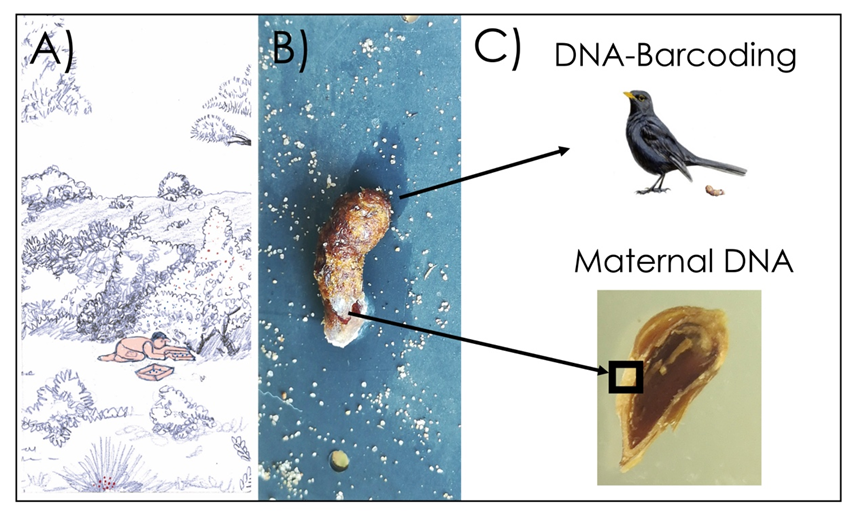

We used DNA-Barcoding techniques to identify the species that fed on J. phoenicea fruits and dispersed its seeds. Additionally, we genotyped the endocarp of the dispersed seeds found in samples. This tissue comes entirely from the mother tree, which produces the seed, allowing us to determine if two dispersed seeds come from the same mother. Using this molecular technique, we were able to identify the maternal composition of the seed rain in all microhabitats and along the expansion gradient.

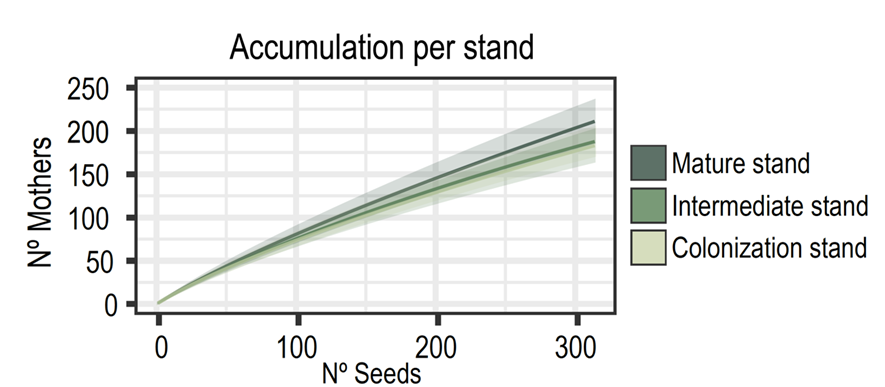

We were absolutely thrilled to discover that the seed dispersal service was equally effective along the entire expansion gradient! This means that seed dispersal is just as effective in the advancing fronts of the population (low juniper density) as it is in the mature forests (high juniper density). Furthermore, as we had suspected, frugivores selectively chose certain microhabitats where the seed rain was denser, such as pine trees for perching and Juniper trees for feeding.

As we knew from previous studies, the assemblage of animals that dispersed Juniperus phoenicea seeds was functionally very diverse. This assemblage was strongly dominated by the main disperser, the song thrush (Turdus philomelos), but was also composed of generalist mammals and several bird species of medium and small size. However, what we did not know until now is the tremendous potential of these species to constantly add new maternal progeny to the seed rain. That is, thanks to their generalised behaviour, feeding on a multitude of different trees and dispersing their seeds in preferred microhabitats, frugivores generated a rich and maternally diverse seed rain along the entire gradient.

Through the application and combination of molecular techniques for the study of plant-animal mutualisms, our study reveals the great potential of frugivores to promote the expansion of populations by ensuring the diversity of seed rain and, therefore, of future forests. Moreover, our results highlight the importance of conservation approaches and strategies focused on preserving and protecting plant-animal interactions that sustain natural colonization processes.