Italy’s 2026 Winter Olympics have been described as the most regionally distributed Winter Games ever staged. Events are spread across more than 22,000 km², taking in Milan, as well as the towns of Cortina d’Ampezzo, Valtellina, Val di Fiemme and Livigno in the Alps.

Geographical dispersion is not entirely new. In 1956, the equestrian events of the Melbourne summer Olympics were actually held 15,500 km away, in Stockholm, Sweden, five months before the rest of the games. This was due to Australia’s quarantine rules. More recently, surfing during Paris 2024 was done in Tahiti, 15,727km from the French capital. The competition was duly labelled “most distant Olympic event ever”.

As a sports management specialist with a human geography background, my research looks at how new spatial solutions and distribution of sport activities and events across a territory increases their sustainability and long-term viability. What distinguishes Milano–Cortina is the way it has been organised across the regions of Lombardy, Veneto and the autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano. This represents a strategic shift towards what geographers would term a “dispersed, multinodal model”. More than 90% of the venues being used already existed or are temporary. The goal is to reduce construction, minimise environmental impact and reduce any long-term maintenance burdens. In other words, the games have adapted to the territory rather than reshaping it.

Learning from past Games

The approach adopted for this year’s games indicates that national organising committees, and the International Olympic Committee (IOC), are willing to adapt. Research shows such a shift is long overdue.

Olympic planning has long involved sustainability rhetoric. Recent reforms emphasise reduced environmental footprints and the use of existing facilities. Yet, events including the Paris 2024 summer games, have been accused of greenwashing.

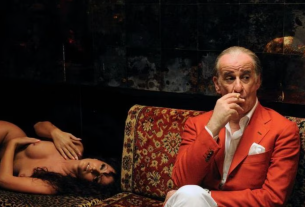

EPA

Italy’s own experience, during the Torino 2006 winter games, highlighted the risks of overbuilding in fragile mountain environments. Many of those purpose-built facilities faced long-term operational and ecological challenges.

Organisers are getting much better at designing flexible venues that can be adapted by the host city for use after the event. In Paris, 95% of the venues were either pre-existing or temporary. The games notably transformed the river Seine into a venue for the opening ceremony and aquatic events. It was expensive to pull off, but as a demonstration of public space reuse and long-term urban ecological investment, it was symbolically powerful. The Place de la Concorde was also converted into a temporary street-sport hub. This showcased how urban environments can host dynamic youth events that blend competition with city life.

Winter games, of course, face different constraints. Where summer hosts can absorb scale, winter hosts rely on natural landscapes that are already under severe climatic pressure. This increases both the stakes and the complexity of sustainable design.

On one hand, spreading events across regions makes them more accessible to multiple communities. It involves more municipalities and regional bodies in planning, implementation, and legacy building, which in turn can foster stronger local engagement and a more distributed sense of ownership.

On the other hand, the model requires robust coordination between diverse actors. It also poses the risk of a fragmented Olympic identity. And it makes media coverage more complex. While this drives innovation in terms of hybrid reporting tools and local storytelling, it can lead to platforms prioritising some events over others.

The transport challenge

The most significant sustainability challenge remains transport. A dispersed model inherently requires athletes, officials, media and spectators to travel more between places. According to the IOC, Milano–Cortina 2026 relies heavily on trains and shuttle systems to minimise private car use, with the goal of reducing car use by 20%, compared to Torino 2006.

Overall travel demand is, however, more complex. A 2022 study on preparations for Milan–Cortina, showed that the larger the host territory, the more complex its mobility planning. Participants still have to get to events and the people who live there, meanwhile, “still expect to inherit benefits from any investments made”. Infrastructure upgrades, from rail modernisation to enhanced alpine transit, are duly central to the 2026 games’ legacy strategy.

Long-distance spectator travel, in particular, remains a huge factor in the games’ carbon footprint, whether the event is geographically concentrated or dispersed. Research published by the French government showed that international travel accounted for almost 50% of the Paris 2024 summer games’s carbon footprint.

In sum, from a resource, climate and environmental perspective, Olympic winter games are not justifiable. They inevitably intrude into the natural landscape and despite all sustainability-led reforms, implementation on the ground is spotty. Milano–Cortina 2026 has included some infrastructure projects which reportedly lack environmental assessments or long‑term utility. To what extent this will be offset by the benefits of its geographical dispersion model remains to be determined.

But the public loves them. The Milano–Cortina 2026 approach signals a vital willingness to adapt. As snowpacks retreat, temperatures rise and young people scrutinise what leaders are doing to the environment with ever greater acuity, this might well be the only thing keeping this event alive.