“I first started taking drugs when I was 15,” says 49-year-old Prapat Sukkeaw. “I smoked marijuana, but it was laced with heroin. I felt like I was floating, and it meant that I could forget about all the problems that I faced as a teenager. It was a beautiful feeling.”

Prapat Sukkeaw is one of an estimated 57,000 people who currently injects drugs in Thailand. His drugs of choice, marijuana and heroin, reflect a period in Thailand’s recent history when both illegal narcotics were the main stimulants being trafficked out of the storied Golden Triangle, a remote and somewhat inaccessible region which includes northern Thailand as well as Myanmar and Laos.

49-year-old Prapat Sukkeaw has used drugs since the age of 15.

Employed by a non-governmental organization (NGO), he has on occasion wanted to give up heroin due to pressure from family and friends. Now, he has recognized that, even if he admits to being addicted, taking drugs “is my preference and my right”. He has now started taking the synthetic drug methamphetamine, as heroin has become progressively more expensive.

His focus has moved from abstaining from drugs to living with the side effects and managing the potential harm of their prolonged use, for example by not sharing needles.

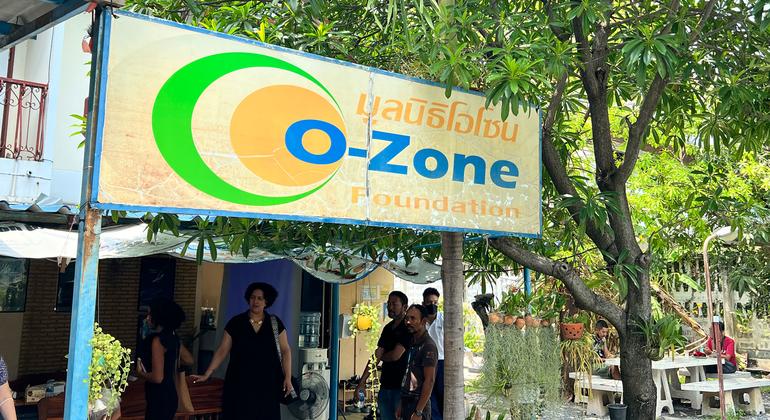

Like all Thai citizens, Mr. Sukkeaw has access to universal health care, but he found that as a person who uses drugs, he was stigmatized and discriminated against by health care workers. He was referred to Ozone, an NGO based in a suburb of the Thai capital, Bangkok.

Ozone’s goal is to reduce the health and social impacts of drug addiction, promoting abstinence, but also supporting clients who want to carry on using and ensuring that they have access to the health services they require.

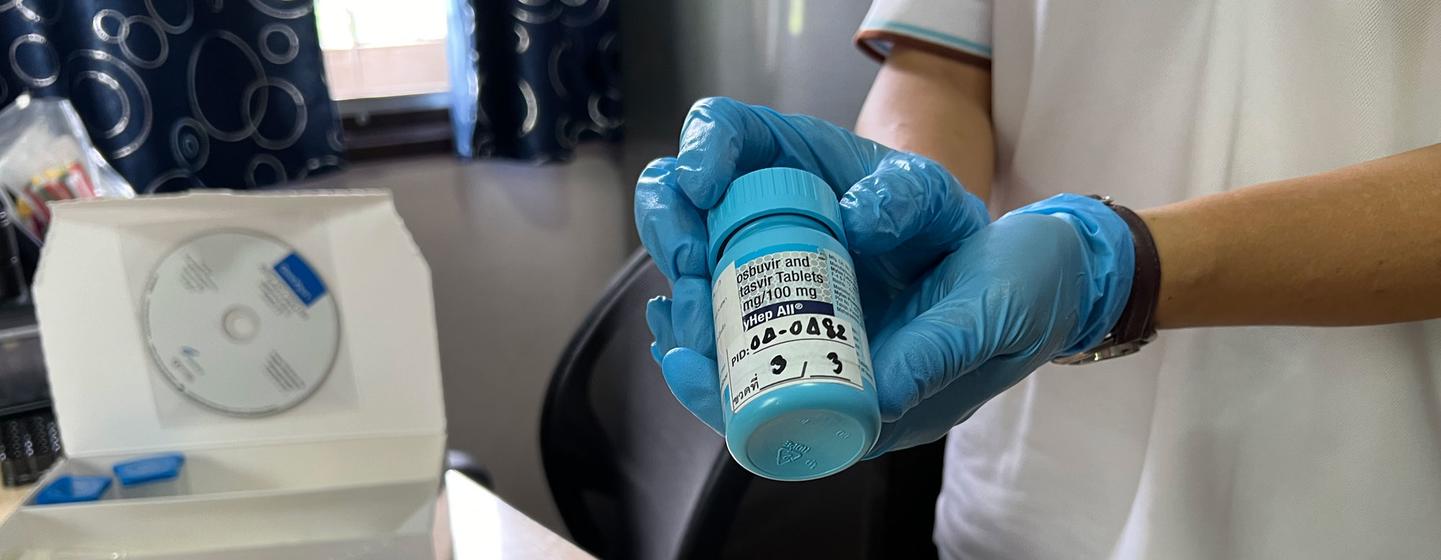

A hepatitis C test is prepared for a client at Ozone.

“Our clients who travel from around Thailand to Ozone welcome our non-judgmental approach,” said Ngammee Verapun, the centre’s director, himself a person who uses multiple drugs on a regular basis. “We are a community which values all people. We are client-centred and offer peer support treating everyone equally, no matter their background.”

Ozone offers a variety of services including needle exchanges and HIV testing as well as PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) which reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex or injecting drugs. It also partners with Dreamlopments, a hepatitis C service provider which offers integrated healthcare free of charge. Hepatitis C is a viral liver infection spread by sharing needles. Its activities are supported by UNODC, although a funding shortfall has meant that the centre has had to close many of its outreach services in other parts of Thailand.

Karen Peters, UNODC.

From punitive to progressive drug laws

Historically, Thailand has severely punished people who have broken strict drug laws. However, since a change in the law in 2021, the legal system has shifted towards rehabilitation for people who use drugs.

Speaking ahead of the International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, marked annually 26 June, Karen Peters, UNODC’s Bangkok-based regional drugs and health focal point, said: “Now people are allowed alternatives. It is not an ideal choice, but they are given the choice to attend a treatment facility or go to prison.”

The law is progressive in other ways, as harm reduction is specifically highlighted as an objective, which, according to Karen Peters, allows organizations like Ozone “to function within the confines of the legal and justice system”.

It is also helping to shift “the narrative around people who use drugs in Thailand from being socially marginalized”, she said.

Tackling stigmatization

The stigmatization of people who take drugs nevertheless continues, but according to Dr. Phattarapol Jungsomjatepaisal, the director of the National Addiction Treatment and Rehabilitation Committee in the Ministry of Public Health, the new legislation means that more “health service providers are being trained to act in a non-stigmatizing manner”.

He says that the reaction from people who use drugs has been “good” as there is a recognition that ultimately, they should receive better care in hospitals and health centres under Thailand’s universal health coverage system, while continuing to have the option to access services in community-led centres like Ozone.

HIV and hepatitis C

One major concern remains the high prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C amongst people who inject drugs in a country where HIV rates are otherwise decreasing. In Thailand, an estimated eight per cent of drug users have HIV, approximately 3,800 people.

The rate of hepatitis C, at 42 per cent, is “very frightening”, according to Dr. Patchara Benjarattanaporn, the country director of UNAIDS, the UN agency leading the global effort to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

Despite ongoing concerns about the health outcomes for people who use drugs, Dr. Benjarattanaporn believes that Thailand could become a model for the region’s countries facing similar challenges.

“The new narcotic law and the community-led aspect of treatment for drug users gives hope that Thailand can control cases, and this is a development that other countries are watching,” he said.

Back at Ozone, one client is receiving counseling about PrEP and HIV prevention, and another is undergoing a hepatitis test. The peer support remains a key element in attracting people to use its services, and it is now hoped that the new legislation will lead to less discrimination and will enable others to access similar services through more government health facilities.