The Paris 2024 Olympics will be “climate positive,” organizers claim. The men’s World Cup in 2026 — to be held in Mexico, the U.S. and Canada — will be the “lowest-carbon FIFA World Cup of the modern era,” if promises pan out.

Qatar’s World Cup ended on Sunday, but climate pledges like its promise of a “carbon-neutral” event — central to the gas-rich Gulf nation’s hosting bid — are staying with the world of mega sporting events.

Real differences among host countries affect how polluting one event is versus another. A country’s size, how many stadiums it builds, whether public transit reaches the venues, and how clean — or dirty — the electric grid is, all factor into the climate impact.

But scientists, environmental advocates and other experts say that sporting events such as the World Cup and the Olympics have grown to such a scale that efforts to make them more sustainable need to go far beyond what was done in Qatar.

“We have to change the structure of these events,” said Walker Ross, a researcher of sports and sustainability at the University of Edinburgh. “And that means having to make some tough decisions about where they can be hosted, and who can host them.”

EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE

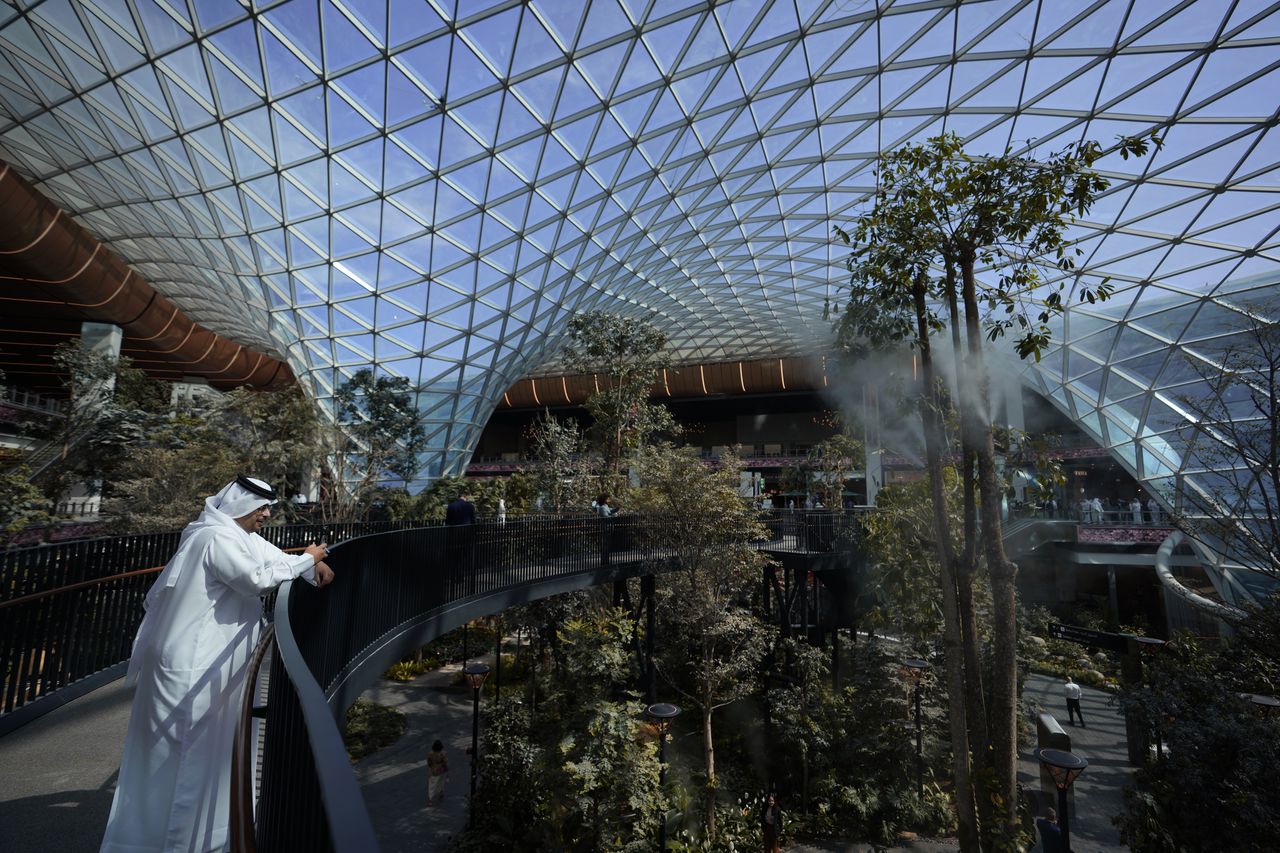

Qatar built seven stadiums and refurbished another for the World Cup. Construction like this is extremely carbon-intensive. The emissions remain in the air for more than a century, changing the climate. And the buildings were just a fraction of what the emirate built to host soccer’s marquee event. Qatar says after the tournament, one stadium will be entirely dismantled.

In contrast, all the stadiums that will host the World Cup games in Mexico, the U.S. and Canada in 2026 already exist. Organizers of the Paris 2024 Olympics say 95% of the venues will come from temporary or existing infrastructure.

Finding potential World Cup hosts who have the infrastructure is easier than for the Olympics, said Andrew Zimbalist, an economics professor at Smith College in Massachusetts who has written multiple books about the economics of mega sporting events.

Summer Olympics can require more than 40 venues, Zimbalist said, “and they’re not venues that are normally used” again.

“It’s a lot simpler to host the World Cup,” he said.

PERMANENT HOSTS

Another idea: establish fixed sites for the Olympics and other events to avoid building expensive infrastructure that often isn’t used after the games, such as the stadiums left behind in former World Cup hosts South Africa, Brazil and Russia.

Some experts say countries could host games simultaneously that way, which could potentially reduce the distances fans travel to a tournament — a major source of emissions for any event.

The International Olympic Committee is considering the idea of a fixed pool of host countries for the Winter Olympics. Earlier this month, the sporting body said it would take more time to name a host for the 2030 games.

Rotating the games “within a pool of hosts” could also be a way to respond to the challenge of finding suitable sites for the winter games on a planet where reliable snow is getting harder to find.

TRAVEL

Reducing how far fans travel to host countries and games is essential, said Arnaud Brohe, chief executive officer of climate consulting firm Agendi and an expert on carbon markets.

Qatar insisted that its World Cup would be sustainable in part because its small size meant fans wouldn’t have to travel far between games. But thousands of fans have stayed in neighboring Dubai in the United Arab Emirates — about 45 minutes away by flight, due to a lack of lodging in the emirate, which is about the size of the U.S. state of Connecticut.

But those distances could be trumped by how far fans and teams will travel during the next World Cup where games will be held in North American cities as distant as Houston, Los Angeles, Toronto and Mexico City. In the bid for the 2026 tournament, organizers said they would try to “cluster” knockout rounds to minimize travel.

MORE ACCURACY

Far-fetched pledges like Qatar’s are becoming the norm.

“When the last one promised to be ‘carbon-neutral,’ you don’t want to be the bid that says the environment is really not that important to us,” said Ross of the University of Edinburgh.

Experts say these plans rely too heavily on promises known as “carbon offsets” to cancel out emissions. Paris Olympic organizers say they will offset whatever emissions can’t be prevented — such as those produced by fans traveling internationally to France.

The credits promise to counteract pollution by paying to bury carbon underground, plant trees or prevent greenhouse gases from escaping in the first place.

But it’s not clear that any sporting body or regulator follows up on the plans after an event. And many carbon experts remain unconvinced by carbon offsets.

“The more of that band-aid oriented thinking we have, the less progress,” said Danny Cullenward, a California-based energy economist and lawyer who studies carbon emissions. “That’s a common problem whether you locate the event in a very high-polluting country or a very low-(polluting) country.”

Zimbalist said sporting bodies should be more honest with their efforts to be sustainable, instead of using labels like “climate positive” or “carbon-neutral” that suggest a mega sporting event will have a negligible or zero impact on the climate, which is impossible.

“A more accurate way of saying it is that they’re less negative, not that they’re positive.”

— By Suman Naishadham, Associated Press

Follow Suman Naishadham on Twitter: @SumanNaishadham

Associated Press climate and environmental coverage receives support from several private foundations. See more about AP’s climate initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.