- Rapid Support Forces and allied Arab militias summarily executed at least 28 ethnic Massalit and killed and injured dozens of civilians on May 28, 2023, in Sudan’s West Darfur state.

- The mass killings of civilians and the total destruction of the town of Misterei demonstrates the need for a stronger international response to the widening conflict.

- Sudan’s warring parties should stop attacking civilians and allow safe aid access. The Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) should investigate these attacks as part of its Darfur investigation.

(Nairobi) – Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and allied Arab militias summarily executed at least 28 ethnic Massalit and killed and injured dozens of civilians on May 28, 2023, in Sudan’s West Darfur state, Human Rights Watch said today. Many of these abuses committed in the context of the armed conflict in Sudan amount to war crimes.

Several thousand fighters of the RSF, the independent military force that has been in armed conflict with the Sudan military since April 15, and Arab militias attacked the town of Misterei, home to tens of thousands of mainly ethnic Massalit residents. The assailants killed men in their homes, on the streets, or in hiding, and fired on fleeing residents, killing, and injuring women and injuring children. These forces then pillaged and burned most of the town, forcing thousands of residents to flee across the border to Chad.

“Since the conflict in Sudan broke out in April, some of the worst atrocities have been in West Darfur,” said Jean-Baptiste Gallopin, senior crisis and conflict researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The mass killings of civilians and total destruction of the town of Misterei demonstrates the need for a stronger international response to the widening conflict.”

Sudan’s warring parties should stop attacking civilians and allow safe aid access. The Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) should investigate these attacks as part of its Darfur investigation.

During a research trip in June, Human Rights Watch interviewed 29 survivors of the Misterei attack who had fled into neighboring Chad. An analysis of satellite imagery and fire detection data shows that six other towns and villages besides Misterei in West Darfur, including Molle, Murnei, and Gokor, were also burned down. Names of people interviewed are withheld for fear of reprisals.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 37 refugees from other parts of West Darfur, including El Geneina and the villages of Tendelti, Adikong, and Molle, who described similar abuses. Widespread and apparently deliberate fire damage was visible in El Geneina, primarily affecting places where thousands of people displaced during previous attacks were living. Human Rights Watch shared its preliminary findings with an advisor to the commander of the Rapid Support Forces, asking questions regarding RSF deployments and steps taken to hold perpetrators to account, but had received no response at time of writing.

West Darfur has been the epicenter of cycles of violence and displacement against non-Arab communities since 2019. In mid-April, as fighting raged elsewhere in Sudan, the Sudan Armed Forces and the local police force stationed in Misterei left the town. In mid-May, the RSF and Arab militias clashed with the town’s Massalit self-defense group.

On May 28, the RSF and Arab militias, many on motorcycles, horses, or pickup trucks, surrounded the town and clashed with the Massalit fighters. The assailants, armed with assault rifles, recoilless rifles, rocket-propelled grenades, and vehicle-mounted machine guns fired on town residents who tried to flee.

“The Rapid Support Forces and Arabs shot at us from behind,” said a 76-year-old man. “I saw three people running, being shot at, and fall to the ground near a grocery store.”

The attackers pursued people who sought safety in schools and the mosque. Many women and children, and some members of the self-defense group wounded earlier, fled to a school complex, on the northern edge of the town, where the assailants repeatedly entered classrooms looking for men and summarily executed those they found.

Two women who had sheltered in a school said that the attackers summarily executed three men and sprayed a classroom with bullets, severely injuring three women and two children. “They were asking about the youth … protecting the village,” one woman said. “Where are the men? Where are the boys? We want all of them! We want to kill them! Why didn’t you just flee and leave the country? Why are you still here? What are you waiting for?”

Throughout the day, the attackers looted residents’ property, stealing livestock, seeds, money, gold, mobile phones, and furniture.

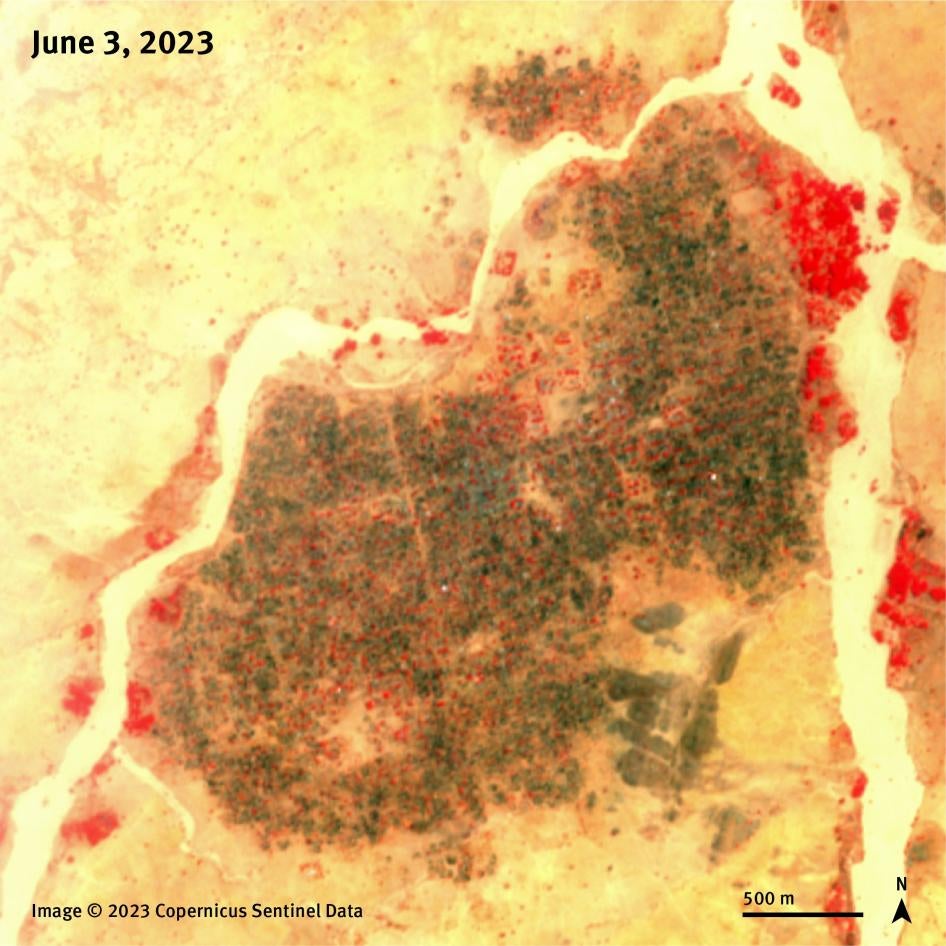

After pillaging homes, the assailants set them ablaze. “The whole town was covered in smoke,” said a 35-year-old nurse. Satellite imagery analysis confirmed the near total burning of the town, particularly the residential areas.

The attacking forces withdrew that evening and residents began the search for survivors and bodies on the streets and inside houses and schools. The remains of at least 59 people were buried in mass graves. Local officials said 97 people were later confirmed to have been killed, including self-defense force members. Human Rights Watch recorded the killing of at least 40 civilians, including a woman, and injuries to 14 civilians, including 5 women and 4 children.

Since the outbreak of the conflict in April, over 300,000 people have been displaced within West Darfur alone, according to the United Nations, and about 217,000 have fled to Chad. About 98 percent of those registered arriving in Chad have come from the Massalit community. About 17,000 refugees from Misterei remain in Gongour, Chad, near the border. The humanitarian response in Chad remains significantly underfunded.

Relief operations largely stopped in late April in West Darfur following attacks on humanitarian aid and property, as well as widespread insecurity in the region. An aid worker said that Darfur has been “largely cut off from new assistance.”

The UN Security Council should call for immediate safe and unhindered humanitarian access throughout Darfur. Security Council member countries, other governments, the European Union, and the African Union (AU) should urgently adopt and enforce targeted sanctions against those responsible for serious abuses regardless of their position or rank.

The Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC should investigate the attack on Misterei and other villages and towns in West Darfur as part of its Darfur investigation. The Prosecutor should highlight investigation plans during his scheduled briefing to the Security Council on July 13.

“The accounts of those who survived recent attacks in West Darfur echo the horror, devastation, and despair of Darfur 20 years ago,” said Jean-Baptiste Gallopin. “The ICC Prosecutor should investigate these heinous abuses, while Sudan’s international and regional partners should sanction RSF and Arab militia leaders responsible for these attacks.”

For details of the abuses in Misterei on May 28,2023, please see below. The names of those interviewed have been withheld for their protection.

Abuses in West Darfur

The magnitude of the violence since April in Darfur is significant even in a region that has witnessed countless atrocities against civilians for two decades. Over 400,000 Darfuris were already refugees in Chad as a result of earlier violence.

West Darfur experienced large-scale abuses in the 2000s including ethnic cleansing, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

Since 2019, Massalit and other non-Arab communities, many displaced since the conflict of the early 2000s, have borne the brunt of renewed attacks by Arab militias, supported by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Sudanese government security forces, responsible for protecting civilians since UN/AU peacekeeping forces pulled out of Darfur following the termination of its mandate in late 2020, have repeatedly failed to protect targeted communities. Self-defense groups have emerged in some Massalit communities.

The town of Misterei, 42 kilometers south of El Genaina, West Darfur’s capital, and 7 kilometers from the border with Chad, is home to about 46,000 people. Its residents are from largely farming communities, primarily Massalit, but also ethnic Zaghawa and Bargo, and nomadic Arab communities. The town has at least six schools, a hospital, a police station, a courthouse, a stadium, and a market that serves as the commercial hub for area villages.

In 2020, tensions between the Massalit population and Arab neighbors resulted in an earlier attack on Misterei. Local sources said Arab militias attacked three neighboring villages in May and Misterei in July, in retaliation for the alleged killings of Arab civilians by armed Massalit. In July 2020, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the West Darfur Doctors Committee reported that hundreds of Arab militiamen attacked Misterei, resulting in the death of at least 60 Massalit civilians. The attack followed the formation of an armed Massalit self-defense group in the town months earlier.

In late April 2023, following the outbreak of the conflict in Khartoum between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF, some local police and the army garrison withdrew from Misterei without informing local leaders or residents. Residents said their departure left the town vulnerable. Previously, “attackers would often not progress further in[to] town,” said one resident. In an attack, the “local community [would] find safe refuge inside the army garrison.”

On May 26 and 27, RSF and the Arab militias began to mobilize on the outskirts of the town. Residents said they harassed people who ventured out of the town and clashed with a Massalit armed group positioned on the Dorondi mountain, 8 kilometers west of Misterei. Another self-defense group was mobilized on the Shorrong mountain, about 450 meters southeast, to protect the town. Residents said they began to fear that the town itself could come under attack.

May 28 Attack

The attack began shortly after sunrise on May 28. The assailants came in several waves from the western side of the town, flanking it to the north and the south.

Residents said that the attacks appeared to be coordinated. Those on foot entered houses, followed by those on motorbikes, who chased residents on the streets. RSF pickup trucks reportedly secured neighborhood entrances and exits and shot at civilians fleeing, even from a distance.

The assault started at the Shorrong mountain where self-defense group fighters had deployed. A fighter, 30, who was there, said:

Around 5:30 a.m., the fighting started at our position, from the southwest. We only had Kalashnikovs [assault rifles]. Arabs and the RSF came in large numbers, first on foot [and] then on motorbikes: the first wave [was] around 400 men on foot; the second wave, 150 to 200 motorbikes; the third wave, six RSF vehicles which I recognized by their emblem; and [in] the last wave [there] were a lot of horses.

The Massalit fighters had split into groups of 7 or 15 fighters, across several locations in town, people interviewed said. At least three vehicles with fighters from the Sudanese Alliance, a predominantly Massalit armed group headed by the late West Darfur governor Khamis Abbakar, were positioned near the market.

Witness accounts suggest that the RSF and Arab militias quickly overran the Massalit fighters, forcing their retreat. Many were killed. Attacks continued through the morning, with a lull around early afternoon, and resumed briefly mid-afternoon.

Human Rights Watch was unable to verify the number of fighters in the town itself that day and how many were killed during the fighting.

Unlawful Killings and Injuries

Residents described scenes of panic and horror as the attackers spread across the town while fleeing civilians filled the streets. The assailants shot people on the streets, including women and children, and stormed houses.

A man, 40, said that at about 7 a.m. he opened the door of his house after hearing gunshots in his neighborhood of El Shati and saw Arab men armed with assault rifles, machine guns, and Rocket Propelled Grenades (RPGs), going door-to-door and shooting wantonly: “Two RSF vehicles [stopped] near my house and shot at those fleeing,” he said. As an RSF fighter assumed a shooting position, “someone cheered him…: ‘Kill the slave! Kill the slave!”

He said Arab militiamen then entered his house and shot his cousin “many times, in the chest,” killing him. He said he then jumped over the wall and ran for safety.

Another man, 60, said that he opened the door to his house that morning and “saw Arabs on motorbikes shoot two young men on [his] doorstep who were running for their lives.” One of the victims died instantly, he said, and he tried to help the other, whose arm was injured. But “Arabs on foot appeared … entering houses and shooting inside,” so he also had to flee. “The Arabs shouted at me to stop but I didn’t. They shot at me, and one bullet went through my right shoulder.”

Women, children, and some men – including injured men – began to flee to the town’s main school complex. School buildings in Darfur are often seen as a safe place during attacks.

“The number of attackers around us was so high,” said a 20-year-old woman who ran with family members toward a school with “a huge number” of people. The attackers shot and killed three people running around her. She said:

Khadija [had] a horse and was holding the horse to take it with her to the school. They stopped her and told her: “You leave that horse!” but she refused, and they shot her. And when they looked to that man [an imam], they … shot him and they shot my brother.

She said the assailants shot both her brother and Khadija in the head.

A woman in her thirties said that when she opened the door to her house, she saw “so many Arabs. A group of them looked at me and shot in the air: ‘Get out!’ Another one asked: ‘Where are the men? Where are the weapons? We don’t want anyone here!” After she fled with 10 children of her family, the assailants shot and wounded her daughter and grandson:

[The assailants] were running and we were running, too. There were more of them, some who were running behind us, and some we came across, who were in front of us. So, they were surrounding us … They were shooting … When we … reached the Adwa neighborhood … they shot my daughter and my grandson.

A bullet hit her 18-year-old daughter in the hip from behind, she said, while her 3-year-old grandson was shot in the thigh.

Another man, 76, said he saw Arab attackers shoot three men from behind while they were running on the street in the Al-Emtidad neighborhood. Separated from his family in the ensuing stampede, he hid inside the Atik mosque, near the school complex:

I met an old man there. We both hid [on the pulpit] … An armed Arab man came in and ordered [us] both to step down. As we were doing so, he shot the … man in the chest and [the man] fell to the ground. He shot [at] me too. His bullet passed over my ear … then he left. The other man bled to death there and I then covered him with a rug.

Summary Executions, Shootings in Schools

RSF and Arab militias pursued scores of civilians who sought to hide in schools. At least eight times that day, assailants entered classrooms and summarily executed the men they found there, witnesses said. They also shot at children and women and robbed them. Eleven survivors, including one local self-defense group fighter who hid in a school after being injured, provided accounts of 26 killings. Witnesses said there was no fighting in the schools complex.

Two women said that while they were hiding in a classroom of the secondary school for girls with about 50 people, most of them women and children, RSF fighters and Arab militia men broke into the room and shot dead three men who had sought protection there. The assailants also fired at children and women, severely wounding several.

A 35-year-old teacher said:

“When we went into the classroom, we locked it from inside. So, they just kept knocking on the door aggressively. When we didn’t open it, they just shot at the door. They pushed it [open] and just started to shoot randomly everywhere.”

The men killed were 20-year-old Hussam Abdu Ahmed; Al-Tahir Ali, a policeman; and an older man known as Al-Haj, an imam at a local mosque. Three women were severely wounded, among them a teacher in her 40s who was shot in the chest, and a woman, also in her 40s, who was shot in the hip. The teacher’s 5-year-old son was shot in the face and chest. A 15-year-old boy was shot in the hip and a 16-year-old girl in the forearm. All were later treated at a hospital in Chad.

A woman, 19, said that in another classroom, about 50 people, mostly women, were hiding. Some were hiding boys under their traditional long dresses. Two men, one in his 30s and the other one older, were also hiding in their midst. Fighters arrived at the school in an RSF car. “[They] entered the classroom,” the woman said. “[They] shot these two men and … put the gun to my head and [to the heads of] other women, asking us to give them money, gold, phones.” The two men died instantly, she said.

In the primary school for boys next door, a 35-year-old teacher who was then nine-months pregnant, said eight RSF fighters entered the classroom where she had sought protection with about 20 people. When the assailants entered, one of the men in hiding had been trying to provide first aid to two men who had suffered gunshot wounds on their way to the school. The teacher said:

I told Hussam [one of the men], “I can put on the Dettol [antiseptic]. Go, they will kill you!” … Before [Hussam] tried to move out they … entered the … classroom and shot all of them, the two who had been injured and the three who had carried them … [Hussam] they shot in the head.

She said one fighter shot other people in the room. “One attacker looked at me and shot me … in my [abdomen].” She experienced a stillbirth five days later.

A 20-year-old woman said that about 11 a.m. at the primary school for girls, which is part of the same complex, she was hiding in a classroom full of women along with five men in their 30s and 40s covered in the women’s garments. She said that when a group of militiamen came in, “they were asking about money and phones. They started to search our items, so they found these men.” The assailants took the men outside and shot them, killing three and wounding two.

Human Rights Watch also spoke with two men who hid in the schools and survived.

One, 35, said he had been shot in the right shoulder while fleeing from his house in the Al-Emtidad neighborhood. With the help of others, he arrived at the secondary school for girls and concealed himself among women and children. He said that in the afternoon, Arab militia men entered the school:

I heard and saw armed Arab men entering the school, shouting, “Where are your men?” Immediately, they found six men and shot them at close range. I don’t know if they [the victims] [had been] wounded before or [if they were] fighters. I saw that from where I was hiding. They spared the children and women. They then left. When they left, I moved to see what happened [and] saw the six men lying there dead. There was so much blood on the floor … [W]omen and children [were] crying.

A self-defense fighter said that, after being injured in the shoulder during fighting, he hid in a large room of the high school for boys, where he survived an attack:

The school was full of women and children mostly … There was a wounded man next to me … The Arabs came saying they are looking for men and to finish the job … The armed men approached us and immediately shot us. They shot the man in the head, then shot me in the leg and, when I flipped, in my buttocks. I lay motionless and was bleeding. My wife started shouting and crying … They thought I was dead, so they left. The other man died instantly.

Two men who were hiding near the schools overheard the assailants cheering and uttering racial slurs. One said: “Some Arabs were cheering and shooting in the air, saying, ‘We burned the Massalit, we burned the zorga [Black people].”

Pillage, Arson

The attackers throughout the day looted at gunpoint farm animals, vehicles, furniture, money, gold, food, and personal items, loading the property into vehicles and on motorbikes, while setting on fire many buildings in the town. A health worker in Misterei said the assailants also “ransacked and looted” Misterei’s public hospital, taking essential and life-saving medicines.

A 63-year-old man living in the Al-Shati neighborhood said that attackers broke into his home, where neighbors had gathered when the attack started: “Arabs … took everything we have. I saw them taking bags of seeds, beans, bread, and wheat, and [then they] left.” In other homes, the assailants stole solar panels, doors, and windows, “food items such as peanuts … blankets, beds, mattresses,” jerrycans, and chairs, and dishes, and cooking utensils.

A 25-year-old man said he was driving into the Al-Shati neighborhood when the attack started, and that men in RSF uniforms fired at him, apparently to stop the car. “A bullet went through the windshield and hit me in my left shoulder,” he said. “I immediately fell out. They pushed my body [out of the way] and drove the car.”

A 60-year-old man with a bullet wound hid in the house of an acquaintance, where two women tended to his wounds. He said that at one point, 10 RSF fighters entered the house, though they did not see him. “The [women] were begging the soldiers not to kill them. The soldier said: ‘We are only here for men or money.” The women gave the soldiers some money, and the soldiers left, the man said.

A 20-year-old student said:

They kept looting, going, and coming back … So around 10, 11 a.m. they went out of the village, near the valley, then returned at 12:30 p.m. They went out again at 3 p.m. and came back again.

Around 4 p.m., assailants returned after briefly leaving the town, a 36-year-old man said. He watched in hiding from the roof of his house in Al-Emtidad:

Arabs [were] roaming around our street looting everything: television screens, furniture, window frames, and bags of seeds [and] loading these onto motorbikes and vehicles, including RSF [vehicles].

At the schools, attackers plundered the valuables that civilians had taken with them. “They took blankets, mattresses, beds, money, phones … donkeys … and they burned the remaining stuff,” said a 20-year-old woman farmer who was robbed. A teacher, 35, estimated that in addition to the gold and phones that the assailants took from people hiding in classrooms, they also stole more than 50 farm animals, including horses, donkeys, and goats, from around the schools.

The attackers set houses and the market on fire as they progressed through town. Eight residents interviewed said their houses were burned. A 29-year-old living in Al-Adwa neighborhood said that he saw militiamen burn his house using a lighter on the thatch roof while he ran away amid intense shooting by the assailants.

Many residents described finding the ruins of their homes when they emerged from their hiding places at sunset, after the attackers left Misterei. They found only remnants of items the assailants had not looted, such as clothes or blankets.

Fire detection data provided by NASA’s Fire Information for Resource Management System showed active fires over Misterei every day from May 29 to June 2. Several smoke plumes and active fires were visible on satellite imagery from May 29 and June 2. Images from June 3 showed extensive burn marks throughout the town’s residential areas.

The Aftermath

“Everything was lost in couple of hours,” said one resident. “There were houses, huts, and shops. When we left our hiding [places] by sunset, there was nothing really left, and many people were looking for the missing ones.”

On the evening of May 28, men began gathering the bodies of those killed for burial. Some residents used folding beds and others a pickup truck to collect the bodies. A front-end loader was also used to transport the bodies and dig mass graves.

A local leader who participated in the burial process said the front loader was used to dig two long trenches and two smaller ones in the yard of the school complex, and that at least 59 bodies, most of them of men, were buried there that evening. The fear of renewed attacks meant that not everyone could be buried that night. A local official said that some people returned in subsequent days and buried more victims, bringing the total number of residents confirmed killed to 97.

Survivors estimated that between 50 and 60 residents were injured. Many of them could only find medical treatment after crossing the border to Chad.

Throughout the day and evening, many residents fled Misterei toward the border with Chad, seven kilometers away. The way out of Misterei was strewn with bodies, two residents said.

A 36-year-old woman described crossing the seasonal riverbed that separates Sudan from Chad:

[W]e saw several dead bodies, clearly people who had been trying to flee before us … maybe three or four dead men, all with gunshot wounds, just horrific. My daughter was pregnant … she couldn’t … deal with what she saw. She miscarried and lost consciousness.

A 35-year-old farmer said his relative, a 45-year-old farmer, was shot in the shoulder while walking towards the border.

By May 31, nearly 17,000 people had arrived in Gongour, a Chadian village across the border and the main point of arrival for refugees from Misterei. Most of these people currently remain in Gongour.

Recommendations

All parties to the conflict in Sudan should:

- Abide by their obligations under international humanitarian law, particularly to protect civilians and facilitate aid delivery; and

- Recognize that commanders responsible for abuses, including as a matter of command responsibility, could be subject to future prosecution before the ICC or another court.

The UN Security Council and AU Peace and Security Council should take meaningful action to address serious violations in Sudan, including:

- Press the warring parties to ensure that all aid and health staff, and humanitarian and medical facilities and supplies are protected from attacks and looting, and that health and aid staff and agencies are able to carry out their work free of harassment or other interference;

- Use existing authority or authorize new targeted sanctions on leaders of Rapid Support Forces, the Sudan Armed Forces and armed groups responsible for serious abuses against civilians;

- Call on all countries to respect the Security Council’s Darfur arms embargo and stop transferring weapons, ammunition, and material to the warring parties;

- Publicly call on Sudan’s warring parties to cooperate with ICC investigations, including surrendering fugitives, and support the court’s work in Sudan including investigating ongoing abuses in Darfur; and

· Call on the Sudan Sanctions Committee to make public any relevant findings related to abuses in Darfur.

The UN Security Council Sudan Sanctions Panel of Experts should:

- Investigate, identify, and name those responsible for abuses in West Darfur and request the Security Council to sanction them.

The UN Human Rights Council should:

- Convene an urgent debate or special session on the situation in Darfur and ensure the participation of Darfuri civil society groups;

- Urgently strengthen and ensure full resources for substantial independent monitoring and investigations into the crisis in Sudan, including events in Darfur, with the aim of collecting and preserving evidence of crimes under international law by warring parties and other armed groups there.

The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the High Commissioner’s Designated Expert should:

- Convene an urgent briefing on the situation for UN member countries, in line with the high commissioner’s independent mandate, to advise them on urgent steps to prevent further abuses in Sudan, including Darfur;

- Allocate adequate resources to significantly ramp up monitoring and regular public reporting on the rights situation in Sudan including in Darfur and take measures to address impunity for serious abuses.

To the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court:

- Investigate recent events in West Darfur as part of its overall investigation into crimes committed in Darfur; and

- Indicate investigation plans with respect to recent crimes in Darfur in the prosecutor’s July Security Council Darfur briefing.

International and Regional donors should:

- Significantly increase humanitarian support both in Sudan and in Chad, and in other neighboring countries to help ensure civilians fleeing from the conflict and communities receiving them can receive assistance.

The European Union, and other concerned governments including the United States and the United Kingdom should:

- Use existing authority or authorize new regimes to impose targeted sanctions on leaders of Rapid Support Forces, the Sudan Armed Forces, and armed groups responsible for serious abuses against civilians; and

- Strengthen existing mediation capacities, such as the appointment of the US presidential envoy, to engage directly with regional actors and Sudanese civil society groups to develop a strategy focused on protecting civilians.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights should:

- Establish a commission of inquiry to investigate serious violations of international humanitarian law in Darfur; and

- Identify those responsible for abuses under the African Charter with a view to holding alleged them to account.