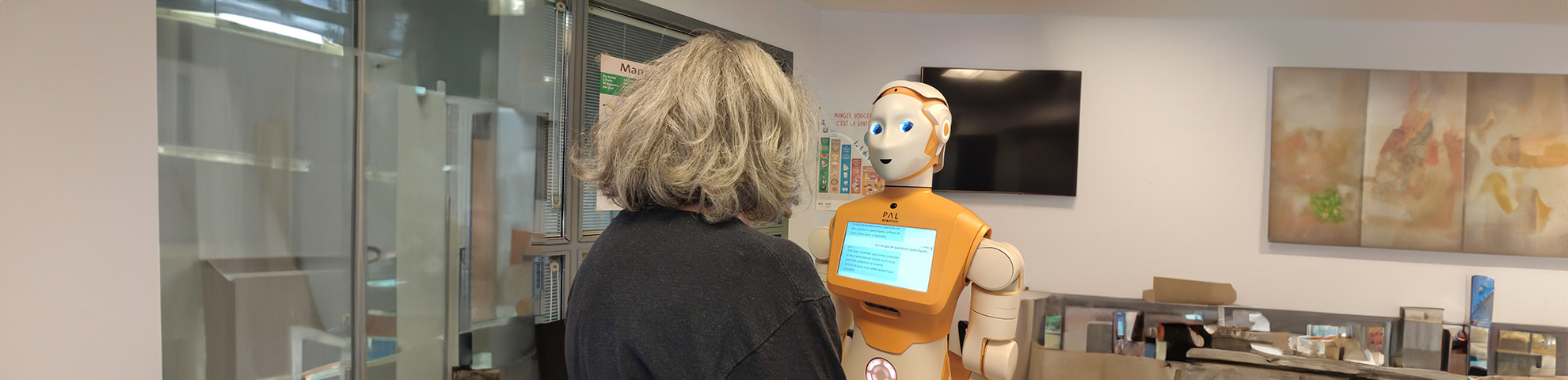

A hospital in central Paris has had an unexpected helper: a full-sized talking humanoid robot. Created by an international team of EU-funded researchers, it can interact with patients, provide practical information and answer questions to help people navigate around the hospital.

Trials of the orange-and-white robot named ARI have shown promise, according to the team at the Broca Hospital, which specialises in day care for elderly patients with conditions like Alzheimer’s and other cognitive impairments.

Cutting through the noise

The challenge was to have the robot understand when it is being spoken to in a busy environment, be able to talk to different people and answer their questions while appearing friendly and non-intimidating to the patients.

In a video filmed by researchers during trials, an elderly lady approaches ARI to ask directions to office 253. The robot blinks, turns its head and replies: “Office 253 is located in Building B, on the second floor.”

This is the type of social engagement that ARI was designed for. And it represents an important milestone in the development of systems capable of interacting with humans.

These robots need to integrate sophisticated speech recognition, noise-cancelling technologies and adaptive communication strategies to ensure effective interactions even in challenging, noisy environments.

Helping hand for healthcare

The hope is that robots like ARI could take over some of the non-medical tasks in hospitals, freeing staff up to focus on patient care. This would offer much-needed assistance to the often underfunded and understaffed healthcare sector.

The research was part of a four-year EU-funded initiative called SPRING coordinated by the French National Institute for Research in Digital Science and Technology (INRIA). The SPRING research team included experts from Czechia, Israel, Italy, Spain and the UK who came together to address the specific challenge of robot communication in a real-life setting involving multiple parties.

“

When the robot works well, people are happy to talk to it.

Their initial development and validation phase concluded in May 2024 with promising results.

“We believe that the ARI robot could in the future become an essential element of patient care in hospitals, thanks to its capacity for social interaction and guidance,” said Professor Anne-Sophie Rigaud, a geriatrician and psychiatrist from Greater Paris University Hospitals, one of the partners in the research team.

Testing conversations

ARI was tested through interaction with over 100 patients, their companions and medical staff, with constant tweaks to improve the quality of the conversations conducted along the way. It became clear that people received the robot more warmly as those improvements were made.

“That’s very promising because it could have happened that even when the robot worked well, people didn’t like interacting with it,” said Dr Maribel Pino, a cognitive psychologist heading the Broca Living Lab, which is responsible for the introduction of innovative health technologies at the hospital.

Pino called the results encouraging, given the current primitive nature of socially intelligent robots, and said they could be a starting point for robots to provide complementary care functions.

“We saw people engaging with the robot,” she said. “When the robot works well, people are happy to talk to it for some minutes.”

Pino said the robots can also provide a conversational distraction and entertain people as they are waiting in the hospital by, for instance, telling jokes. Such mental stimulation could be useful for people with cognitive impairments.

Navigating acceptance

Although socially assistive robotics has come a long way in recent decades, most of today’s robots are designed for single-user interaction in a few simple scenarios at museums, shopping centres or hotel reception desks.

One challenge to the more widespread use of robots in public places is the plethora of legal and ethical restrictions on using autonomous machines and collecting data, especially as robots could also potentially process biometric data and health records.

Since the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act entered into force in August 2024, certain obligations have been imposed on AI developers to balance innovation with safety, ensuring that conversational robots operate within ethical and legal boundaries.

Data protection concerns meant the robot at the Broca Hospital had to be confined to a separate room and stand still rather than roam about, for instance.

Moving forward

According to Dr Xavier Alameda-Pineda, a computer scientist and roboticist at INRIA and the person responsible for the coordination of the work carried out by the SPRING team, significant advances have been made, despite the challenges.

Initially, progress was made as the robots were trained on large language models – advanced AI learning systems designed to understand, generate and manipulate human language. This allowed robots to engage in a more natural conversation.

“

We now have the first system that can interact with two people.

Further technical improvements were then made before the final tests, including adding head movements to allow the robot to better interact with people and ‘look’ directly at them.

PAL Robotics from Barcelona, Spain, which manufactured the robot, has continued improving it following the end of the validation phase in Paris.

New features include automatic speech recognition and improved gaze-following algorithms. These will allow ARI to better detect social cues. PAL Robotics has also been conducting further pilot projects using the robot for assisting and interacting with older people in residential homes in Spain, Italy and Greece.

Furthermore, ARI robots have been developed and tested in SPRING’s research labs in other countries, including Czechia, Israel and the UK.

Social intelligence

The SPRING researchers also progressed in another key area: enabling the robot to interact in more complex conversations involving more than one person and detect whether it is being addressed or not.

“We now have the first system that can interact with two people,” said Alameda-Pineda. “That’s a huge step.”

But creating more sophisticated robots that fully understand social cues and non-spoken conversational gestures such as nods, quick looks or shrugs is a much bigger conundrum.

“What’s complicated is for a robot to get a grasp of the more subtle aspects of social interaction, such as irony, gestures, facial expressions, and combinations of those things,” said Alameda-Pineda.

He believes that a talking robot providing basic conversation and interaction, as well as giving appointment advice and directions, could be ready for widespread use within a few years.

The advances made by the SPRING team put Europe at the forefront of work being done in this field, thanks to their robots’ natural conversation style and ability to interact with several people at the same time. Separate research in the EU, Japan and the US has produced similar robots, but they either lack ARI’s ability to multitask or have been too costly to produce.

Research in this article was funded by the EU’s Horizon Programme. The views of the interviewees don’t necessarily reflect those of the European Commission. If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.