Shortlisted for the Georgina Mace Prize 2022

In their latest research, Kieran Gething and colleagues use a citizen science habitat survey to predict the richness and rarity of invertebrate communities in frequently inundated river sediments in order to guide monitoring and management of these dynamic habitats.

River channels and their surrounding areas are dynamic ecosystems in which the extent of water varies in space and time. Fluctuating water levels, for example in streams that dry out, allow such ecosystems to support diverse aquatic and terrestrial invertebrate communities that include rare species.

However, changing water levels mean that sampling either aquatic or terrestrial communities in frequently inundated areas can be challenging for scientists, managers and citizen scientists alike.

Recent development of citizen science habitat surveys has expanded opportunities to characterise habitat conditions such as physical complexity and human disturbance. Terrestrial invertebrates respond predictably to such conditions and thus, in this study, we predicted the richness and rarity of terrestrial species in two frequently inundated habitats using data from a citizen science physical habitat survey.

Predicting richness and rarity of an invertebrate community

We used terrestrial invertebrate communities sampled from exposed riverine sediments (ERS) and dry streams to represent the biodiversity in frequently inundated habitats. We documented the amount of disturbance by humans and the environmental characteristics of invertebrate sampling sites using the Modular River Survey (MoRPh), a citizen science habitat survey.

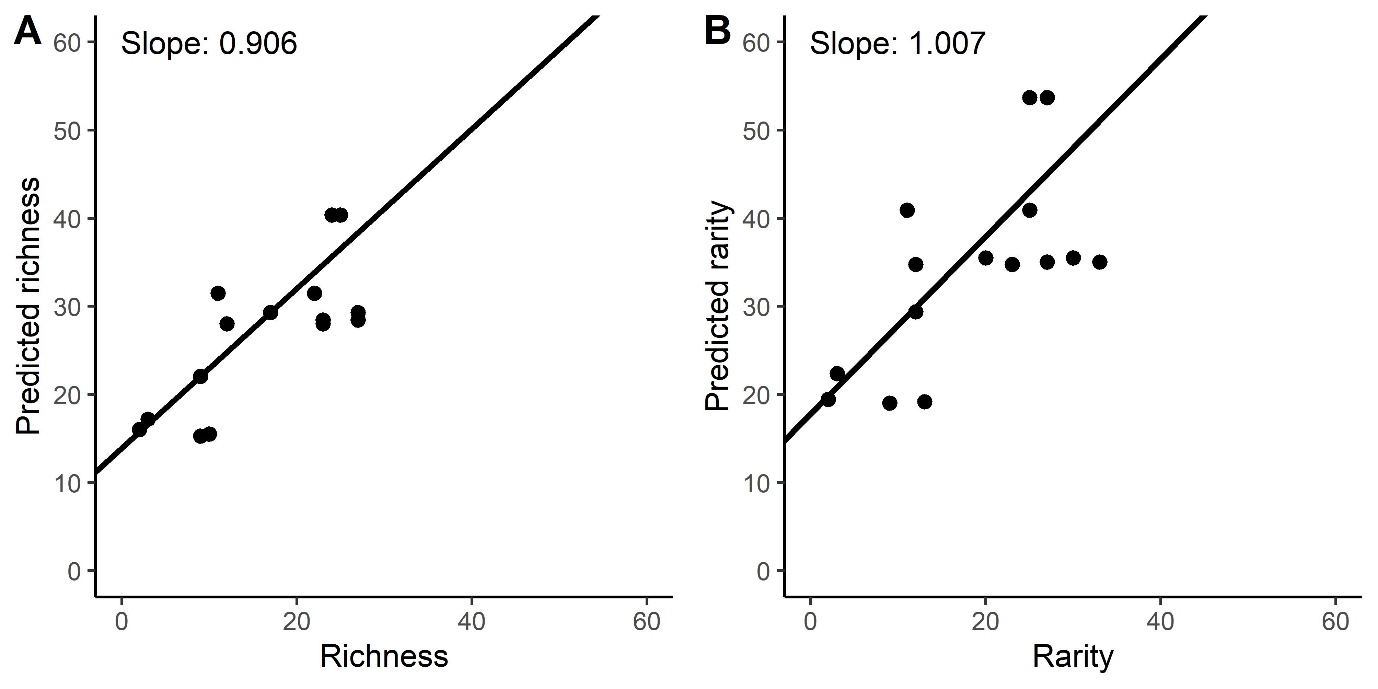

We then used part of this paired invertebrate/habitat dataset to characterise the relationship between habitat conditions and invertebrate richness and rarity. These relationships, alongside habitat conditions at other sites in the dataset, was used to predict the richness and rarity of terrestrial communities in the remaining invertebrate samples. Finally, we assessed the effectiveness of our predictions by correlating observed with predicted richness and rarity.

Can richness and rarity actually be predicted from a habitat survey?

The simple answer, yes! Our predictions of the richness and rarity of terrestrial species in ERS were correlated with those observed in the sampled invertebrate communities, suggesting that physical habitat conditions can predict community characteristics.

Predicted and correlated richness and rarity were also correlated in dry streams, suggesting that such predictions may be transferable among a range of frequently inundated habitats.

Monitoring and management implications

Aquatic and terrestrial habitats are often monitored separately, leaving the dynamically inundated areas in and around river channels infrequently monitored, or with only the aquatic communities characterised.

One reason for the lack of terrestrial monitoring is that sampling terrestrial invertebrates in frequently inundated habitats can be challenging. For example, setting and collecting ‘pitfall traps’ (buried plastic cups that invertebrates fall into) requires multiple visits with days-to-weeks in between, and samples may be lost if water levels rise between visits.

Some methods, such as searching for invertebrates by hand, can collect a sample in a single visit but are only used when a site is not inundated. Our predictions thus enable professional and citizen scientists to characterise terrestrial communities from habitat features that are present regardless of inundation.

As well as logistic challenges, a lack of time and money also hinder the extent of ecological monitoring. The expansion of citizen science initiatives including simple habitat surveys such as MoRPh may thus enable more widespread monitoring of frequently inundated ecosystems, which can be used to provide insights to the terrestrial communities that sites may contain.

The challenges associated with monitoring frequently inundated ecosystems mean that evidence to inform site-specific management actions is often sparse, but our predictions of the richness and rarity of terrestrial communities may be used to guide and prioritise such actions. For example, our predictions could identify site characteristics that promote high biodiversity or allow prioritisation of management actions at sites with greater differences between observed and expected (i.e. predicted) community characteristics.

In summary, although directly sampling terrestrial invertebrate communities in frequently inundated habitats is the best way to characterise them, such sampling can be resource intensive and its success depends upon dynamic environmental conditions (i.e. inundation).

Our predictions of invertebrate community characteristic from simple habitat surveys could promote greater inclusion of frequently inundated habitats in ecosystem health assessments and provide evidence upon which to base management actions when sampling is prevented by inundation or logistics.

Read the full article: “Living on the edge: predicting invertebrate richness and rarity in disturbance‐prone aquatic–terrestrial ecosystems” in Issue 3:4 of Ecological Solutions and Evidence.

Discover the other early career authors shortlisted for the Georgina Mace Prize 2022.