- The Philippine authorities have sought to permanently move entire communities from various areas to sites deemed safer, without adhering to international standards aimed at protecting the rights of those affected.

- Past failures in the region underscore the urgent need for authorities to ensure inclusive, rights-based solutions, including through fully consulting those affected.

- The Philippines government should develop rights-respecting planned relocation, and international organizations and donors should provide their support.

(Tokyo) – Philippine authorities relocating communities displaced in 2021 by Typhoon Odette have ignored the rights of residents, especially those with disabilities, Human Rights Watch said today. Initiatives for relocation on Siargao island in the southern Philippines have lacked meaningful consultation, accessible information, and inclusive participation, undermining rights and putting residents at risk of future extreme weather events.

In December 2021, Typhoon Odette—known internationally as “Rai”—swept across the Philippines, including Siargao, flattening homes, killing hundreds of people, and displacing thousands. Entire coastal communities were left without shelter, clean water, or access to public services. People with disabilities and their families described significant obstacles in evacuating and staying safe during and after the storm. Since then, the Philippine authorities have sought to permanently move entire communities to areas designated as safer, called planned relocation, without adhering to international standards aimed at protecting the rights of those affected.

“Siargao island authorities have relocated people, including those with disabilities, to sites that are inaccessible and lack basic services,” said Emina Ćerimović, associate disability rights director at Human Rights Watch. “The Philippine government needs to fully consult people with disabilities and the wider community to ensure that future planned relocations uphold their rights.”

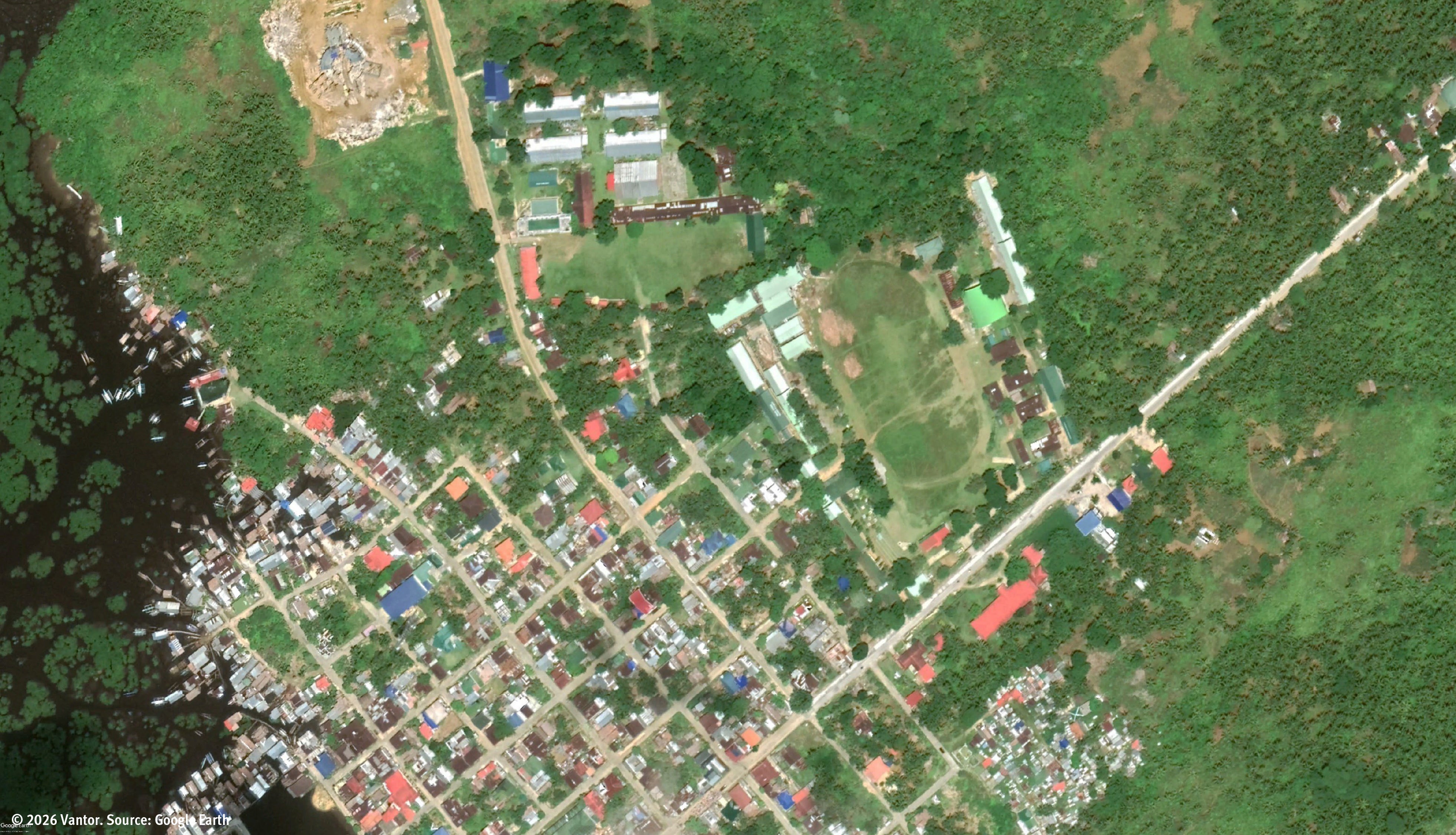

Between May and September 2025, Human Rights Watch interviewed 48 people, including 25 people with disabilities and their families who live in 4 municipalities on Siargao island—Del Carmen, Pilar, San Isidro, and Santa Monica—community representatives, climate change experts, United Nations representatives, and government officials in Manila, Butuan City, Surigao City, and Siargao.

“My husband carried me on his back through the floods,” said Jocelyn Iytac Eguna, 65, who has a physical disability, describing the typhoon that devastated Siargao and nearby islands. “I felt I had lost hope and really wanted to die. It’s really difficult for me. Other people can just run away but I had to be carried.”

Following Odette, the Philippine government instituted a No-Build Zone policy in coastal and riverbed areas of Siargao, part of the protected conservation area, to prevent residents from returning to their homes “for their own safety.” However, the authorities did not meaningfully consult displaced communities about their needs and preferences for the future, nor did they offer those displaced adequate alternative housing or sufficient information on plans to provide a durable solution.

In the past decade, storms in the Philippines have displaced at least 43.8 million people. As climate change accelerates, the number of those displaced is expected to increase. A recent study found that human-induced climate change has “more than doubled the likelihood of a compound event like Typhoon Odette.” In November 2025 alone, two back-to-back typhoons in the country affected more than 12 million people, causing hundreds of fatalities and displacing more than 466,000 people, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

Under the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, competent authorities have the primary duty and responsibility to establish conditions for a durable solution for people displaced by disasters. International standards set out three durable solutions for the displaced: dignified return, local integration, or permanent planned relocation to a new, comparable site. Most residents displaced by Typhoon Odette immediately returned and rebuilt homes in the No-Build Zone, where they face an uncertain future.

Because people’s lives, livelihoods, and identities are deeply tied to their homes, climate adaptation and disaster prevention measures that allow people to remain in place should be prioritized whenever possible. According to the UN Guidance on Planned Relocation (2015), planned relocation should be considered only as a last resort to protect life and health, and based on consultation with affected communities or at their request.

Municipal governments on Siargao have responded in various ways to the typhoon and the No-Build Zone designation. Immediately afterward, the San Isidro municipal government undertook, without consulting the affected families, an unplanned and inadequately supported relocation of 40 families from the San Isidro riverbank to Josephath, a site uphill, which has undermined their rights. Community members and local government officials said that relocated families have inconsistent access to water and difficulties in accessing the river and services in the community. People with disabilities are particularly at risk of injury and lack of access due to the inaccessibility of the site.

Similarly, the Pilar municipal government, with support from the International Organization for Migration (IOM), moved several families to a site that the local community said floods regularly, undermining the whole purpose of relocation. As a result, during extreme weather, the families remain cut off from access to the rest of the village, including the local primary school, which also serves as an evacuation site.

The municipalities of Santa Monica and Del Carmen, which are currently developing planned relocations, should learn from these mistakes and act to ensure a rights-respecting process, Human Rights Watch said.

Mayor Alfredo Coro of Del Carmen acknowledged that the municipality had yet to consult affected communities but expressed his commitment to make the planned relocation human rights-centered and disability-inclusive. If Del Carmen’s planned relocation successfully upholds human rights, it could serve as a model for municipalities across the Philippines, and perhaps in the 77 other countries where disaster-related planned relocations have been documented.

The Philippines is obligated under international human rights law to respect, protect, and fulfill everyone’s economic, social, and cultural rights, and to protect them from reasonably foreseeable climate change risks, including sea-level rise and other climate change impacts. Under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), authorities at all levels are obligated to ensure protection and safety of people with disabilities in situations of risk, including disasters.

As the national and local governments expand planned relocation in Siargao, it is crucial for them to safeguard human rights through meaningful consultation and accessible information. Ensuring the rights of those most at risk, including people with disabilities, will result in better protection and safety for all, Human Rights Watch said.

“The Philippine government and international donors should provide local authorities in Siargao with sufficient support to develop durable solutions for those uprooted by Typhoon Odette or increasingly exposed to climate risks,” Ćerimović said. “Climate change magnifies existing inequalities, and past failures in Siargao underscore the urgent need for authorities to ensure inclusive, rights-based solutions, including through planned relocation.”

Relocations on Siargao Island

Typhoon Odette

On December 16, 2021, Typhoon Odette made landfall in the Philippines, including on Siargao, claiming hundreds of lives and destroying numerous buildings, affecting 99 percent of the Siargao’s population. People with disabilities and their families described facing significant barriers while evacuating and trying to stay safe during and immediately after the storm.

Jocelyn Iytac Eguna, 65, who has a physical disability and uses crutches, has lived all her life on Halian, a small, flat island in the Dinagat Sound two hours by boat from Siargao. When Odette struck, her house was damaged and she became trapped inside with her husband. Feeling she was a burden, she urged her husband to save himself. “But my husband said he wouldn’t leave me because I have a disability,” she said through tears:

My husband carried me on his back through the floods, with electric wires damaged and down, and coconut palms falling around us. He carried me all the way and stayed with me. I felt I had lost hope and I really wanted to die. It’s really different for me: other people can just run away and I couldn’t. I needed to be carried. The next few days were difficult: there was no food; we survived mostly on coconut water.

Eguna said the trauma left her with deep psychological wounds. When asked if she had received any psychosocial—mental health—support, she responded, “None. You are the only one who had come to ask me how I feel.”

Many other people with disabilities described similar experiences:

- Ronie Ticmon Ruaya, 50, a polio survivor who also lived all his life on Halian, said he decided to stay home with his wife and his children during the storm: “It’s really difficult because of my disability.… If you don’t have polio, you can just immediately run fast, but because of my condition, I just can’t.”

- Mary Jane Bual, from Jaboy in Pilar, also decided not to evacuate. Her 16-year-old son has intellectual and physical disabilities, and she said he does not always understand or respond well to changes. “It’s hard to explain to John Francis why he needs to leave the house,” she said. “We could have just forced him to leave by carrying him. But we decided to stay and shelter together.”

- An aunt of a 12-year-old boy with developmental and physical disabilities on Halian described his extreme distress as the family tried to shelter inland without adequate protection from the storm and elements. “It’s really a big difference [compared with other children], because he can’t speak,” she said.

Following Typhoon Odette, the national government instituted a No-Build Zone policy alongside Siargao’s coast to prevent displaced residents from returning to their homes. The government stated it was for safety reasons, but ultimately neither the national nor local authorities provided communities with durable solutions through rights-respecting planned relocation. The authorities did not meaningfully consult with the communities about their needs and preferences, and most received no visits from the authorities. In the days and weeks that followed, without any other options, most returned and rebuilt their homes there.

Applicable International Law and Standards

International human rights law on planned relocations is set out in various human rights treaties that the Philippines has ratified, notably the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. It is also established in international standards and guidance, such as the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Framework on Durable Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons, which authoritatively interprets to comply with international legal obligations, and the Guidance on Planned Relocation, to help governments plan and carry out relocations of communities at risk in a rights-respecting manner.

With regard to the specific needs of people with disabilities, Philippine government officials acknowledged national laws and policies guaranteeing disability rights, including the National Adaptation Plan of the Philippines, the Magna Carta for Disabled People, and the National Resettlement Policy Framework. But they said that no practical measures are in place to safeguard disability rights, including to inclusion and participation, accessible information, protection and safety, accessibility, or access to public services.

Unplanned Relocations: Pilar and San Isidro Municipalities

In Siargao’s Pilar municipality, the local government with the support from IOM relocated several families from Jaboy village to a nearby site. Community members reported—and Human Rights Watch observed—that the new site floods regularly, cutting residents off from the rest of the village and the only evacuation site. This is particularly dangerous for Jimilito Gonzales, a 48-year-old man with an intellectual disability, who doesn’t know how to swim and relies on his brother to reach safety. His brother said:

We carry him there [to the village]. I would place him on the makeshift raft made of banana leaves and push the raft. Sometimes, the water is up to our necks, and sometimes it’s above our head and we need to swim and push the raft.

IOM confirmed that the organization’s primary support was in providing climate resilient housing for the site, but that they also supported pre-relocation assessments and consultation efforts in Pilar. IOM emphasized that responsibility for determining site suitability rests with the local government and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, which, according to IOM, issued a certification confirming the site’s suitability for relocation, noting that the area had a low flood and low landslide susceptibility rating. Nevertheless, IOM acknowledged that assessments based on historical hazard data can be limited in their ability to foresee future hazards. To address this, IOM said it is collaborating with governments to improve site assessment methodologies, including by modeling future risk patterns, and interviewing community members with lived experience.

Regarding consultation, IOM said they consulted affected families in Pilar, including by sharing information about the site and arranging visits before relocation. However, a relocated resident said that “we had no choice,” as they had lost their homes and the site was the only land available, despite being known to flood regularly.

IOM representatives as well as local government officials acknowledged that land availability is a major constraint and said they had not received formal complaints about flooding in Jaboy from the local government or community members. Nonetheless, based on the concerns reported by Human Rights Watch, IOM said it was committed to “coordinate further with the communities and local and national partners to understand what further support is needed, explore comprehensive solutions, and advocate for potential means through which these needs could be met.”

The IOM reiterated that long-term responsibility lies with the local government, and recognized the need to build capacity at local levels.

While other community members who remained in Jaboy believed that the municipal government had a plan to relocate them to safer areas, Pilar’s representatives said there were no such plans for Jaboy.

Immediately after Typhoon Odette, authorities in San Isidro municipality relocated several families from the riverbank in San Isidro to Josaphath, an uphill location originally intended as temporary. Officials and an elected representative said in May 2025 and again in September that the site had become permanent because it is considered safe from flooding, and it was easy to move people there because the local government already owns it.

However, community members and local government officials agreed that the site lacks regular access to water and the steep road isolates people with disabilities. Zenaida Tomines, 52, who has a physical disability, said she fears another big storm since the evacuation site—a primary school—is down the same steep road. “I am afraid for my own safety because of my disability,” she said. When Human Rights Watch asked San Isidro officials about plans to address the accessibility problem, they said there were no plans to address it.

Planned Relocation: Del Carmen Municipality

Typhoon Odette caused severe destruction in Del Carmen, the island’s largest municipality, destroying nearly 5,000 homes and displacing thousands of residents. Essential services, including water and electricity, were widely disrupted. Local authorities believe that their eight-year effort to restore the mangrove forests prior to Typhoon Odette had helped reduce the storm’s impact.

To carry out the No-Build Zone policy, the municipal government has been preparing permanent planned relocation sites. The authorities intend to relocate about 1,000 households to three sites, including the entire population of Halian island, which the authorities say will become uninhabitable due to rising sea levels. Other high-risk coastal communities in downtown Del Carmen are also expected to be relocated, though timelines are unclear.

In the nearer term, the municipal authorities intend to relocate about 250 households from Halian to Mabuhay, on Siargao. The authorities selected the site because it provides easy access to the ocean, which enables the predominantly fishing community to maintain their traditional livelihoods, reflecting some consideration of residents’ livelihood needs.

The Del Carmen government has been working closely with the Philippines Department for Housing Settlement and Urban Development (DHSUD) and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to secure approvals and funding for the relocation. Mayor Alfredo Coro told Human Rights Watch that the municipality is committed to building the first 10 houses even if they do not have full external support.

So far, however, the Del Carmen authorities have not consulted with those they intend to relocate or taken steps to learn of their needs and concerns. A representative of the DHSUD in Butuan City, which oversees Siargao island, said in September that if approved the project would include social preparation and consultations “to ensure community acceptance.” This approach, however, does not meet international standards for meaningful consultation since it suggests a predetermined outcome rather than information exchange, genuine engagement, and collaborative decision-making.

When responding to a question on ensuring inclusion of people with disabilities in Del Carmen’s planned relocation efforts, the representative said: “We have really good laws, but implementation is slow. [There is] a lack of funding, not a lack of willingness to respond to the needs of people with disabilities.” In a May 2025 interview, Mayor Coro conceded that disability-specific rights and needs had not been discussed.

Existing plans reviewed by Human Rights Watch did not incorporate accessibility or disability-inclusive design, including accessible routes. Mayor Coro said he was committed to adapting the plan to respect human rights, including disability rights. “We are more active in collaborating with people with disabilities sector [and encourage them] to be more vocal of their demands, so we can hopefully provide services that they want.”

Key Human Rights Issues Relating to Planned Relocation

Consultation

Under international human rights law, planned relocation needs to be preceded by meaningful, informed, and participatory consultation with affected communities, as required by the rights to an adequate standard of living, and access to information, among other rights. Beyond ensuring that planned relocation is a measure of last resort, national and local governments have an obligation to ensure that affected communities are meaningfully involved in decisions about a potential move. This includes the right to be informed, offer input at multiple stages of the process, and to have their views taken into account before any final decisions are made. The Guidance on Planned Relocation emphasizes that planned relocation should be voluntary and conducted in a way that respects the human rights, dignity, and safety of all.

Mayor Coro acknowledged that consultation had been lacking: “We didn’t consult much the community, because we wanted to first ensure we would have legal opinion to identify the land that can be used. We don’t want to provide false hope, without first finalizing the relocation site.”

A government official from Del Carmen said that a public hearing for the relocation of the Halian community was held on Siargao island in September 2025, making participation nearly impossible for Halian residents, particularly people with disabilities, due to the costly two-hour boat ride. The official confirmed that only people in positions of authority were invited and that organizing the consultation in Halian was beyond their budget.

For people with disabilities, who have historically been excluded from decisions affecting their lives, the right to be closely consulted and actively involved is crucial. Article 4(3) of the disability rights treaty obligates governments to closely consult with and actively involve people with disabilities through their representative organizations in policy development, planning, and implementation.

The UN Guidelines on Consulting Persons with Disabilities details how inclusive consultation helps ensure that policies, strategies, and programs are effective; that barriers to inclusion are identified and addressed, and, in the context of planned relocation, that the process responds to everyone’s needs. Consultations should be timely and frequent, and include reasonable accommodations, accessible information and communication, sufficient preparation time, and physical accessible venues.

Philippine law and policies, notably the Philippines Post-Disaster Shelter Recovery Policy Framework, identifies consultation as a core component of recovery efforts.

People with disabilities and local government representatives in Siargao said that authorities did not meaningfully consult or involve people with disabilities in the relocation plans, including those carried out San Isidro and those planned for Del Carmen. None of those interviewed reported having been consulted or involved in decisions regarding planned relocation.

Johanna Mary Pacle, 21, who has a physical disability and lives in Del Carmen’s No-Build-Zone, said, “As a person with a disability I am used to not being consulted. I would like consultation so I can learn more.”

Her father, Junuan Escanan, 48, said little information had been provided: “We are still waiting to actually see what plan the government has, it’s rather become a rumor now than reality. I don’t know where and when, it’s just talk.” He emphasized the importance of participation: “I was born in this home. I would like to be consulted if there are plans to move us.”

While some municipal officials said they were concerned about building expectations, early and inclusive consultation with communities is crucial for effective and dignified solutions. Evidence from the special rapporteur on internally displaced persons in a 2024 report shows that outcomes are better when relocated communities have information about options and are involved in the decision-making about whether to relocate.

Right to Information

Everyone interviewed for this report said that the authorities had provided no information about relocation plans, and what they knew was mostly rumors from other residents.

The right to information is a core component of a human rights-based approach to planned relocation. Moreover, the 2010 Framework provides that “[n]ational and local authorities … need to provide IDPs [internally displaced persons] with all the information they require to choose a durable solution, while also ensuring that IDPs can exercise this choice without coercion.”

Relocation fundamentally alters people’s lives, and they have the right to receive information throughout all stages of the process, so they make informed decisions, including whether to relocate or remain. Information should be provided in a clear and accessible manner and should include anticipated disaster and climate risks as well as the social, physical, and economic impacts of the relocation.

The 2015 Guidance provides that adequate, advanced, up-to-date, and accessible information on the rationale for relocation, as well as alternatives considered, is essential to minimize the risk of forced evictions.

Under the disability rights treaty, the government is obligated to ensure that people with disabilities can “seek, receive, and impart information on an equal basis with others and in all forms of communication of their choice,” including accessible formats and technologies, such as sign language, Braille, and easy-to-read formats. The goal is to ensure information is accessible, understandable, usable, and supports autonomy and equal participation.

Arnold Alaban, 43, a vendor with a physical disability who lives in the Del Carmen No-Build Zone, said that he had not received any concrete information about the planned relocation efforts. “I’m not really informed about it,” he said. “I don’t know anything, just that it means that people have to move. No one spoke directly with me about it.”

Ruel de Rosario, 48, who also has a disability and also lives in Del Carmen, said that the last time he heard anything about the No-Build-Zone was immediately after Odette. “The DENR [environment department] posted signage over this area after Odette. The signage was removed after a couple of months.” He and others said they had never received official information about risks or plans for relocation, relying instead on rumors.

The lack of reliable information has raised concerns among many residents on Halian island and Del Carmen’s downtown coastal area that they will be forced to relocate without their consent. In May 2026, Mayor Coro said that they do not intend to forcibly relocate the residents and the same was reiterated by a Del Carmen official in January 2026 regarding the Halian community.

Right to Housing

Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognizes the right to housing as a component of everyone’s right to an adequate standard of living. Many current residents of Del Carmen are “tenured migrants,” people recognized under Philippine law for their long-term, subsistence living for which they are granted rights to stay in the protected area. The Siargao Islands Protected Landscapes and Seascapes Act recognizes the occupancy of families who lived on the land for five or more years before the island was designed as a protected area for conservation in 1996.

The law further provides protections in case “these areas are subsequently identified as crucial for conservation” to be transferred to “alternative sites … provided that their transfer shall be undertaken using humanitarian considerations including payment of compensation, providing tenure to alternative land and facilities of equivalent standard, and other measures to reach agreement with the affected tenured migrants.”

The 2015 Guidance sets out that if the government later uses the vacated land, it “should ensure that land vacated in a Planned Relocation is used in a manner that … enables Relocated Persons to retain access to that land and its resources, to continue their preexisting livelihoods, and to maintain spiritual and cultural practices, for as long as practicable.” This would be applicable, for instance, to displaced residents from Del Carmen’s coastal communities whose land was used for an expanded port or tourism purposes, or those on Halian if tourism were expanded on the island.

People with Disabilities, Durable Solutions and Views on Relocation

Most people with disabilities and their families living in the four municipalities on Siargao island said that they wished to stay, citing their strong ties to the land, reliance on livelihoods linked to the ocean, and the ability to easily access needed services. Ruel de Rosario, 48, who has a physical disability, said, “I’ve lived here since birth. My mother, who is 77, lives here as well as my 18-year-old daughter.” Analyin Rosas, 27, who has a disability, said, “I’ve lived here since I was born, my father was also born in this house.”

To make informed decisions about whether to relocate or remain, community residents need information responsive to their concerns. Those in Siargao who expressed a willingness to relocate emphasized the need for clear information and assurances that they could work in the new site and earn an income sufficient for an adequate standard of living. They also hoped relocation would provide secure, permanent housing.

“I’d agree to be relocated to have a house of my own,” said Arnold Alaban, who sells small items to tourists at the Del Carmen port, “It would have to be not far from where I would be able to make a living.”

Rosas, said, “I’ve lived here since I was born. My father was also born in this house.” She has no independent income and lives with her year-old son at her father’s house. She said the relocation “would be okay, but we would need to be near the ocean since my father is a fisherman.” Her father and three adult brothers depend on coastal access to work as fishermen and boatmen for tourists.

For others, relocation raised concerns about losing not just work but their sense of identity. Hasael Compra, 44, who has a disability and has fished since he was 12, said, “It’s my skill, it’s my life, and my livelihood. When I am in the water [fishing], it doesn’t matter if it rains or it’s sunny or windy, regardless of the weather, I like being in the water.”

Suitability and Accessibility of New Sites

Experiences in some Siargao municipalities highlight that poor site selection may have negative consequences for all, but particularly people with disabilities. The officials did not adequately consider disability rights—such as accessibility, safety in situations of risk, or access to services—leaving people with disabilities cut off from accessing community services and at heightened risks during extreme weather events.

The national and local governments, in addition to ensuring that the process of planned relocation respects human rights, are responsible for ensuring an adequate standard of living at relocation sites, including adequate and accessible housing. The disability rights treaty and the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, as well as national law, such as the Philippines Accessibility Law, require the authorities to select sites accessible to all and close to services so that people with disabilities can live independently and participate in the community.

The site in Pilar is frequently flooded, putting people with disabilities at a particular risk. The San Isidro site, which was intended as temporary but became permanent, lacks consistent access to water and is located on a steep hill, making daily life especially difficult for residents with disabilities.

In Del Carmen as well as other municipalities planning relocation, the authorities have an opportunity to learn from the problems in Pilar and San Isidro and design a relocation process that addresses the rights of people with disabilities and their concerns. Rosario described his fears:

I am concerned it will be hard for us to be moved from our homes, and moved where? If there is a house, it would be a better option than if they just moved us to a land with no house. I have a disability now and cannot build it myself. My concern is also being transferred to a faraway place, where it would be hard for me to go to the market. I grew up here. I know everything around here. It’s near the center. I can obtain everything. I can use my wheelchair and get whatever I need.

The relocation site needs to be good for me as a person with disability. It needs to be accessible for people with disabilities, for the wheelchair to be able to get in and out. Transportation is really important because I cannot just walk to the town center, to get to the market or the pharmacy here. Living far away from here would also create additional expenses and limit my access to the market and the pharmacy. Here I can just use my wheelchair and get to all facilities I need.

Pacle similarly expressed a need for physical accessibility and access to work: “I want to be able to walk and use my wheelchair at the new site.”

The 2015 Guidance provides that planned relocation processes need to ensure access to employment opportunities. Relocation sites that isolate communities from employment opportunities or markets may violate human rights obligations. This is of particular concern to people with disabilities, who are protected from employment discrimination under article 27 of the disability rights treaty.

Recommendations

To ensure rights-respecting and all-inclusive planned relocations, local authorities on Siargao island, provincial authorities in Butuan City, and national authorities should:

- Use relocation only as a measure of last resort. Exhaust all possible in-place risk-reduction and adaptation measures before considering moving people. Ensure displaced communities have access to basic services and will not be at greater risk during future extreme weather events.

- Ensure inclusion, participation, and consultation. Ensure the full inclusion of all affected people, including people with disabilities, in decision-making about whether and how to plan relocation. Consultations should be timely, accessible, and designed to ensure meaningful participation to protect everyone’s rights and needs.

- Ensure access to information. Provide clear, up-to-date, advanced and regular information about climate change impacts and plans at all stages of the relocation process in accessible formats (in the local language Surigaonon, Braille, sign language, easy-to-read, digital) and by using diverse communication methods. Access to information is essential to ensure that consent is informed and genuine, and to prevent forced evictions.

- Support rights-respecting durable solutions. Offer displaced families genuine options. Support those who want to relocate out of harm’s way to another site where their rights to adequate housing, education, health, water, accessibility, and culture are fully met. Ensure these options guarantee secure, legally recognized land tenure for relocated households and all individuals within them, including people with disabilities and women.

- Design new sites that reflect the rights and needs of persons with disabilities. Ensure that planned relocation sites incorporate universal design principles and that new housing, infrastructure, and services are accessible. New sites should be selected based on robust assessments, and located near services (including water, health, and education) and enable access to livelihoods to ensure an adequate standard of living. Ensure that policies and practice respect the rights of people with disabilities in every stage of planning and implementation.

- Develop and implement disability-inclusive policy. Ensure that the needs and rights of people with disabilities during planned relocation are included in all related national planning and policy efforts, including on resettlement and relocation, climate change adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and internal displacement.

- International agencies and donors should build capacity of local governments undertaking planned relocations by providing financial and technical support, including on consultation practices and interview-based and future-oriented site assessment methodologies, to ensure that relocation sites minimize ongoing hazard risks and enable continued accessibility, an adequate standard of living and other human rights, and addresses the needs of at-risk groups, including people with disabilities.