For Black History Month, the British Ecological Society (BES) journals are celebrating the work of Black ecologists from around the world and sharing their stories. The theme for UK Black History Month this year is Time for Change: Action Not Words. Perpetra Akite—a lecturer at Makerere University, Dept of Zoology, Entomology & Fisheries Science, Uganda—shares her story below.

The COVID-19 Lockdown in Uganda

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 was reported in Uganda on 22nd March 2020, but it was the 31st March 2020 that will forever remain in the hearts of Ugandans, as this was the day when the first COVID-19 lockdown was announced. No one was prepared—more so the education sector. Everyone was grappling with the uncertainty of the next steps. But if there is one thing that COVID-19 taught us as Ugandans, it was the fact that we will always go back to our roots. Once the timeline for the lockdown was announced, many people opted to return to their village areas if they could. Following this, the reality of what was long forgotten struck many people. A question that was being asked was: how long would this lockdown last? It was indeed unknown and what started as a trial two weeks lasted almost two full years. Many people were far away from familiar things: friends; schools; their environment; etc. The only thing that had the potential to connect us was social media; however, social media was unreliable for those in the rural setting due to lack of data, as was stable access to power or solar energy systems (not many had invested in these at all).

With COVID-19 taking hold in the country, many people did not know what else they could do to keep their sanity. As a field ecologist, everything was bleak. We had no access to field sites, collections at the university, or our textbooks. But a few weeks into the lockdown, social media started to host some rudiments of our ecological settings. People started sharing photographs of the areas they were in, and, once in a while, included some photographs of either an insect or unexpected animal visitors. This made me realise that the majority of us are born potential ecologists, but over time several things seem to compete for our time. Our education system unfortunately does not afford us the luxury of developing our ecological interests together with other professional interests. This means that we often lack the encouragement to pursue some of these interests that are often regarded as a waste of time and badly paid (financially), especially in a society where quick returns are necessary for your work. Children are often discouraged from pursuing mainstream ecology, especially in pre-university courses by parents/relatives and friends. Yet, for those who had the chance to bond with nature earlier in life, there is always that special sense of belonging and appreciation—as was the case once the pandemic struck. Such persons found lockdown to be a once-in-a lifetime opportunity to enjoy nature.

When faced with such a dilemma, everyone is willing to participate in a wide range of ecological activities. Thus, ecological work becomes a community-centric activity where people are openly willing to partake in citizen-science activities and outreach programmes. These activities would generate awareness and, in some cases, provide valuable scientific data that can be used as baseline for long-term research.

What opportunities did we miss?

Since Uganda rolled out a new competent-based curricula for lower secondary schools, environmental education is now incorporated into these curricula. Biology teachers are now responsible for ensuring that the students’ population at large understands the ecological processes on which our lives depend. By showing students how they can participate in resolutions to environmental problems, teachers can make issues discussed in the classroom tangible and applicable. The result is more environmentally aware citizens whose knowledge will benefit society beyond their formal schooling. Unfortunately, the outbreak of COVID-19 happened before all this was in effect in most schools. As such, we missed a number of opportunities, including a chance to collect big data, a chance to have an overview of biodiversity across the country using minimal funding, and a chance to mentor the next generation of ecologists—especially the citizen scientists. Children learn by example and being with their parents was an opportunity to instil some practical skills that would be helpful in influencing tomorrow’s world. It would have also provided much needed materials for discussion at school under the new competent-based curricula where children are encouraged to know more about practical skills rather than theoretical aspects of learning. There’s no doubt that lately many people seek encounters with nature; however, our work-centred lifestyles do not provide for these opportunities. As such, the pandemic provided a great opportunity and silver lining for many to enjoy the environment around us away from our office desks.

Too little, too late?

During the extended lockdowns, did we miss an opportunity for school projects where young minds could have participated in good science? Given that children are curious, they need to be given a chance to observe things away from the classroom. For example, insects that are found everywhere are great models for teaching general scientific and biological principles. They provide an opportunity for young people to engage in real science and practice the process of scientific discovery. For many who chose ecology as a profession, childhood encounters with nature can often be traced to the origin of a life-long curiosity about nature and a passion for learning. This is synonymous with my own story of my journey into ecological studies. The greatest joy in appreciating nature starts at a very young age, just like great scientists such as Darwin and Mendel, whose early-year encounters with nature influenced their decision to carve a path towards becoming great ecologists/biologists. The simple experience of being outdoors and observing the beauty of nature inspires our senses and exposes us to something bigger than ourselves.

How I ecologically navigated the COVID-19 lockdown

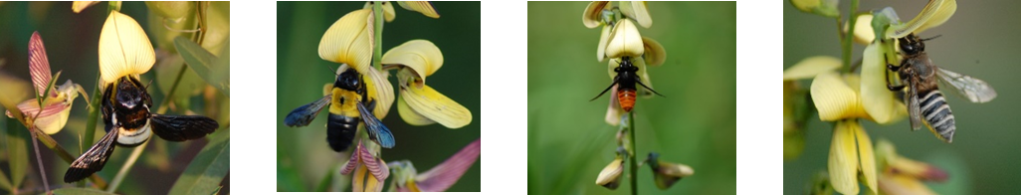

When the lockdown started, I was not able to return to my rural village in northern Uganda, but I was lucky to stay outside the capital city, Kampala. As we know, biodiversity is not only found on the far side of the world, it’s also found in our backyards. With the usual field surveys in limbo, I devised a plan to interact with nature. Right away, I dug out my compound and planted several legumes in the gardens, besides the already established avocado and mango trees. Soon my garden burst in to life, from the visitation of several insects, to birds and even small mammals. These are things I would not see on my usual (yet limited) days spent at home. The icing on the cake was a recording of a flatworm right in my backyard, which I have never seen alive, save for slides. All I could say was, wow! Our university students would now have the opportunity to see a live specimen rather than the usual slides. Thankfully, these worms survive for long periods of time provided there is a wet surface. I am glad that the students had a chance to see an animal that is protected by mucus and moves largely by ciliary gliding. This led me to contact Prof. Mary Wicksten from Texas A & M University (TAMU), who indicated the worm was one of the hammer-heads, genus Bipalium (see image 1). This sighting set me on the path of reading a lot about flatworms, something I had barely done in my ecological journey so far.

Back to my garden. The lockdown gave me the opportunity to not only produce my own food, but also to record several kinds of urban pollinators that exist in my overly built-up neighbourhood—so many bees (both social and solitary), beetles, flies, birds, and others insects! I was able to collect extensive data on insect-plant interactions for which a paper is now in creation. Now, post-COVID-19, I am a proud urban farmer with a number of vegetables flourishing in my small urban space. In Uganda, like many tourist destinations, many local people experience their natural heritage only through visiting the protected parks/areas that often have scenic landscapes, big game, or historical artifacts. They are happy to travel several kilometers in search of charismatic species like lions, however, their immediate surroundings are quite often ignored and no one rolls out their cameras to capture what is right on their doorstep. In Kampala, and possibly other urban cities and towns, there is plenty of wildlife that one can easily enjoy at the comfort of their front doors. Wherever we live, wild creatures, plants, and ecosystems are integral to our well-being, health, nutrition, and way of life. The strong and ancient connections between humans and other living species mean that we cannot really separate ourselves from the ecosystems within which we evolved. Although humans have come to dominate many of earth’s ecosystems, we still rely on these connections, making ecology and ecological interactions a matter of survival. My backyard garden has become my favourite living laboratory where I am able to practice ecology outside the classroom and invite school children in the neighbourhood to learn about nature and why we should preserve it.

Moving ecology to online platforms.

Over the lockdown period, I had the opportunity to be part of number of virtual ecological meetings and discussions. I was invited to the virtual symposium for the Entomological Association of North America. This symposium gave me the opportunity to interact with other ecologists and discuss how best we could continue with our ecological interests during the pandemic where movement and physical interactions were now, for all intents and purposes, non-existent. I was happy to share on the topic “Citizen Science in Uganda: why the slow pace of recruiting disciples?” This opportunity came from my last blog that was published back in 2020 by the BES. After this symposium, I connected with other ecologists from North America who were interested in carrying out work in tropical Africa—especially on dung beetles and butterflies. I also got a chance to be part of a discussion led by Prof. Helen Roy (president of the Royal Entomological Society & CEH) under the theme: Women in Entomology. This gave me an opportunity to interact with several established female entomologists from across the globe working on different taxa, and we shared how different individuals were coping with the effects of the pandemic. The workshop was broadcasted live on YouTube and additional results were compiled into a short publication in Antenna (Antenna 2020: 44 (3:102-105). The most consistent of these webinars was the weekly Biodiversity talks hosted by the African virtual museum under the Biodiversity and Development Institute citizen science department. Prof Les Underhill and his team were great in keeping us engaged in ecological and conservation discussions throughout the lockdown.

With the outbreak of COVID-19, the world faced an unprecedented crisis as we witnessed a human tragedy of historical proportions. COVID-19 knew no borders, spared no country or continent, and struck indiscriminately. COVID-19 was not only a health emergency. It was also an environmental/ecological issue stemming from human interference in nature—including deforestation, encroachment on animal habitats, and destruction of biodiversity. As a country that thrives on tourism, the outbreak of COVID-19 simply cut off a major source of revenue for Uganda. However, one great opportunity for me was the chance to move tourism online. Given that working in ecology means that I have had the opportunity to visit as many places as I possibly can, I resorted to showcasing a number of sites to my national and international networks in the form of photographs and short videos. The extensive feedback gave me a new lease of life on how to approach my own ecological work—to capture data that speaks to a wide array of people, and not only ecologists.

Ecology in post COVID-19 Uganda and the global community.

While the Ugandan Government has taken commendable steps to contain the virus, the post-crisis reconstruction phase should not focus only on health, economic, and social issues. It must also focus on increased efforts to protect the environment. The transition to a green economy, therefore, will require a paradigm shift in the management of natural resources. This calls for major investments in sectors that support ecology and have high green-growth multiplier effects like agriculture, energy, transport, and urban green cities—in doing so, the transformative aspect of urbanization can be harnessed. As we prepare to rebuild the economy, we must not lose sight of environmental signals and what they mean for our future and wellbeing. Urgent action is required to protect and conserve biodiversity, as a key response to the global health and environmental crises, in order to ensure the long-term survival and well-being of our country, and the world! The lesson from COVID-19 is that early action can enable transformational change to accelerate the transition to a greener economy; the health of people and the planet are one and the same, and both can thrive in equal measure. Although many of the threats to biodiversity and protected areas have been exacerbated following the COVID-19 pandemic, we have also seen greater appreciation of nature and the importance of understanding how ecology works. Together, as communities, we can develop more resilient ecological systems for the benefit of nature and people. I believe that this period is just the beginning of long-term collaborations between the north-south partners that can enhance our ecological knowledge through networking, and those of the future generations of ecologists.

Enjoyed the blogpost and want to reach out to Perpetra? Contact her via Twitter or email!