In the last months before the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown I chanced upon the autobiography of Edison Arantes do Nascimento in a local thrift store in Ottawa.

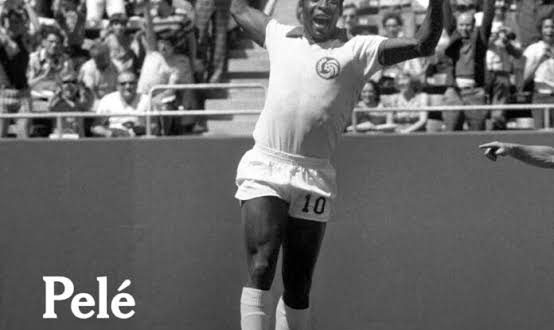

Titled Pelé: The Autobiography (2006), it was one of the books I read during my sabbatical which coincided with the early part of the pandemic. Fondly known as Pelé of Brazil, do Nascimento who is regarded as the god of soccer by some fans is celebrated as the only footballer in history to have won three World Cups – in 1958, 1962, and 1970.

Upon the announcement of his recent death at 82 after battling complications from colon cancer, I picked out the book from the memoirs and biographies section of my home office. I wanted to revisit not just the entire magical volume, but to re-read that chapter of the book titled “Glory” which thrilled me at first reading. Brimming with details of Pelé’s Nigerian connection, it was easy picking out the chapter as I had marked it extensively.

Particularly touching is Pelé’s reporting of an “extraordinary tour” to Africa in early 1969. With his club Santos, Pelé recounts his journey into Brazzaville in Congo. While they were there “the possibility arose for a quick hop to play a match in Nigeria.”

However, at that time Nigeria was in the throes of a civil war with the newly seceded state of Biafra.

Sensing Pelé and his teammates unease, their business manager assured them not to worry as the warring parties would hold a truce in their honour. To which Pelé declared: “He was crazy!”

As Pelé tells it, “all he knew” is that upon landing in Nigeria, he played a game that ended in a 2-2 draw and then flew out again. After the game, Pelé heard that there may have been a 48-hour ceasefire held just for the game.

He later adds: “Well I’m not sure that this is completely true, but the Nigerians certainly made sure the Biafrans wouldn’t invade Lagos when we were there.”

Also in the autobiography, Pelé describes the work of journalists to trace his genealogy. He explains that his real name, Nascimento, belonged to the owner of the plantation where his African ancestors worked upon landing in Brazil.

He has been offered two versions of his ancestry: “One that my ancestors came from Angola, the other that my name came from Nigeria.”

Before his historic trip to Nigeria, Pelé reflected on his first visit to the continent in 1967, and revealed that this visit caused him to “consider [his] own sense of identity.”

He and his teammates visited Senegal, Gabon, Congo, and the Ivory Coast. This was a formative experience for Pelé, as he stated that it changed his perception of the world, as well as “how the world viewed [him].” In one remarkable recollection, Pelé writes:

The interest in the team and in me was extraordinary – tens of thousands of people were at matches, and at the airports when we arrived, and lining the streets wherever we went.

Often the country we were visiting had to deploy soilders just to keep the crowds under control – everyone in Africa, it seemed, wanted to see us, touch us, almost as if they wanted to make sure we were real.

In a sobering, reflective tone, Pelé embraces his identity as a descendant of enslaved Africans, and his experience as a Black man in Brazil. He explains that “slavery is not too far in the past” and that his grandmother, Ambrosina, was the first generation born free – she died at age 97 in 1976. In fact, Pelé is only the third generation of his family to be born free.

Brazil did not abolish slavery until 1888, making it the last country in the Americas to do so. Pelé writes that “The experience of being black in Brazil is sometimes hard to explain. All the races are mixed together — everyone has some black, or indigenous Indian or European or whatever.

In Brazil there were many, many slaves, but after abolition there was never anything like apartheid or segregation, so we have no fault-line between races like in South Africa or US. I have experienced very little prejudice because of the colour of my skin, and I’ve never judged anyone because of it.”

He acknowledges that “Of course racism exists in Brazil, but [he] was fortunate to become both famous and wealthy at a young age, and people treat you differently when you have money and celebrity. It is almost like a race apart-Not black or white, but famous.”

Pelé observes that “Being in Africa was some intensely humbling and gratifying experience” for him. “I could sense the hope the African derived from seeing a black man who had been so successful in the world.

I could also sense their pride in my own pride that this was a land of my forefathers. It was a realization for me that they had become famous on several different levels — I was now known as a footballer even by people who didn’t really follow football.

And here in Africa, as well as that I was a world-famous black man.”

Throughout his life, Pelé cherished his African roots. In 1977, he enthusiastically predicted that an African nation would win the World Cup “before the year 2000.” When this did not happen, he updated the deadline to 2010.

It must be pointed out that Pelé relationship with the continent was not always idealistic.

A South African news and information website, Independent Online, recalls that during his visit to South Africa in the 1960s, Pelé “was not allowed to leave the old Johannesburg airport terminal due to the discriminatory policies adopted by South African law at the time. After being alarmed by this, he vowed that he would never visit South Africa again until Nelson Mandela was released from prison.” It was not until after Mandela was elected the first democratic president of South Africa that Pelé had the opportunity to meet him in March 1995. Pelé would visit again on 17 July 2007 to attend the “90 Minutes for Mandela” match honouring Mandela, who turned 89 the day after his arrival.

He returned in 2010 for the World Cup Finals in Johannesburg.

Another testy moment in Pelé’s relationship with Mother Africa was when Pepsi Cola exploited Pelé’s popularity to promote its brand in Uganda and Kenya in 1976 after Pelé led Brazil to World Cup glory for his third time. As Michael Fitzpatrick reports for rfi in an article titled “Africa remembers special bond with Pelé, the greatest athlete in history,” Kenneth Matiba, the then Chairman of the Kenya Football Federation, snubbed Pelé, arguing that the organization “was unsure if he was promoting football or the sugary beverage.”

Although Pelé’s visits to the continent were punctuated by occasional negative exepiences, Pelé’s legacy is forever tied to his strong African roots. Clément Astruc particularly foregrounds this conclusion in his compelling essay on Pelé titled “Pelé and the world.” According to Astruc, “Pelé’s performances had strong repercussions in the context of decolonization and the emergence of the Third World on the world stage.” Astruc cites the warmth that Pelé received during his tours of Africa and the enthusiastic commentaries about his playing, which I underscore in Pelé’s autobiography excerpted above. Astruc also alludes to a 1969 Jeune Afrique magazine article devoted to honoring Pelé on his 1,000th goal. The author of the article, Mahjoub Faouzi, recognized the footballer as a figure greater than the game. Instead, Faouzi writes that “a black-skinned Pelé is still and above all the embodiment of the advancement of millions of long-despised human beings. Like Malcolm X, Muhammed Ali and Miriam Makeba, Pelé is a symbol and a standard bearer.”

Astruc also quotes a poem by Madike Wade, a Senegalese correspondent of Africasia magazine published the day after Seleção’s third World Cup victory. Titled Pelé, tous les nègres te saluent… (Pelé, All Negroes Salute You…), the poem, according to Astruc, made Pelé a hero of the Black cause:

NASCIMIENTO, you have proven, with your football,

that no race is superior to the BLACK race, that there is not even

any such thing as superior and inferior races.

In any case, you are the KING of the world and you are a

NEGRO. […]

You stand tall, proud and you are especially aware of being a

symbol of the BLACK race.

That is why all NEGROES salute you!10

As the world celebrates the King of Football, and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro declared three days of national mourning for Pelé, Africa and Africans are united in proudly honoring a unique son and a brother who consistently and proudly affirmed his African roots and Blackness with pride.

Nduka Otiono is a writer and the Director of the Institute of African Studies at Carleton University, Canada.