The vast majority of the EU’s agricultural subsidies are supporting meat and dairy farming rather than sustainable plant alternatives. That’s the key finding of our new research, published in Nature Food, in which for the first time we were able to fully account for crops and other plants grown to feed animals.

The subsidies operate through the EU’s common agricultural policy (known as the CAP). This plays a critical role in shaping farming across Europe, but has been the subject of intense criticism for years.

Critics say it supports big landowners over smaller farmers, that its environmental payments represent only a small portion of the budget, and that it is vulnerable to corruption.

While some EU policymakers want to make the CAP more sustainable by including more environmental provisions, they face opposition from lobby groups and protests by farmers. But our work shows these environmental improvements are sorely needed as more than 80% of CAP funds support animal-based products.

These products overwhelmingly drive the EU’s food-related greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity loss, water consumption, air pollution, water pollution and more.

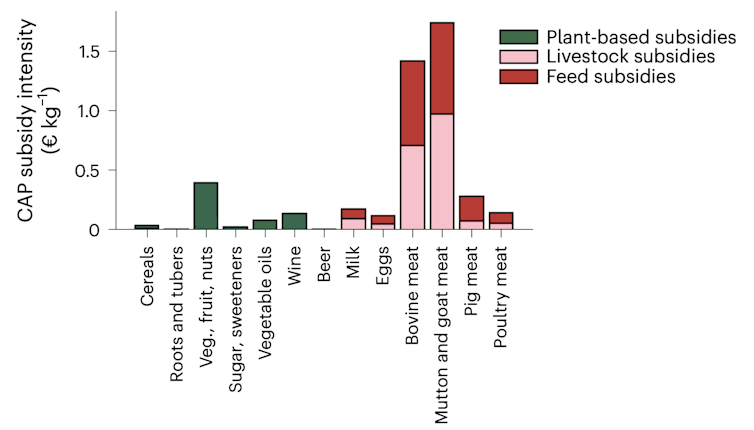

Kortleve et al / Nature Food, CC BY-SA

Meat is cheaper than it would be in a fairer market

The CAP is the largest single EU expenditure, accounting for roughly 38% of total spending. We found that of the €57 billion (£49 billion) annual CAP budget, €46 billion (£39 billion) was directed towards animal-based products, mostly foods like beef, pork, chicken, dairy and eggs.

These estimates are from 2013 – the most recent year for the food supply model we used – but the proportion of the subsidy has changed very little since then. Our estimates are higher than was previously thought because we now have a more complete picture of the subsidies that animal feed also receives.

Kortleve et al / Nature Food, CC BY-SA

For example, a French farmer growing wheat for pig or chicken feed will receive a subsidy for that wheat on top of the subsidy received by a livestock farmer in Denmark who imports that feed. On this basis, we show that CAP support roughly doubles for animal-based foods. For example, beef CAP subsidies increase from €0.71/kg to €1.42/kg once feed is included.

This does not directly translate into the price on the shelves, as there are many other distortions in the current food system. But it gives a sense of the relative difference between animal and plant products.

The result is an uneven playing field in which animal products are cheaper than they would be otherwise, thanks to the additional subsidies. It makes fruits, vegetables and nuts appear relatively more expensive than meat or dairy, which flies in the face of efforts to reduce the environmental damage of the EU’s food system and to encourage healthier eating.

The global food system on its own is enough to blow past the climate targets of 1.5°C and even 2°C of warming. We’ll need drastic action to transition fast enough to not only reduce this environmental impact, but to be resilient to more extreme weather driven by climate change.

Scientific consensus now shows that a shift to mainly plant-based diets is the biggest single opportunity to reduce these food-related environmental impacts, especially in high-income nations.

Such shifts may even release land to help meet climate targets and improve food security. Yet CAP subsidies are perpetuating the existing system, not helping in transitioning the system.

Subsidised food is being exported away

The use of public funds in the CAP aims to ensure healthy, safe and secure food production for the EU. But these subsidies are also influencing production and consumption in other countries that import food from the EU.

We find that 12% of the CAP budget ends up subsiding the price of exports to non-EU countries. Perhaps surprisingly, much of these exports head towards higher-income nations. In fact, in 2013, the US effectively imported more CAP money via food imports from the EU than all the CAP money that went to Denmark.

It’s the same for China, importing more than the money going to the Netherlands. This ultimately makes the convergence on healthy and sustainable diets at the global level more difficult.

More broadly, farmers are under huge pressure from issues such as climate-driven extreme weather and increasing production costs due to inflation. But we know that without significant green reforms – including the reform of the CAP – the increasing costs of environmental damage will make things even worse in future.

To build a food system that is more sustainable, more resilient and better for public health, farming subsidies will have to be reformed. The recent watering down of green EU policy is a step backwards, and can only be an act of self-harm over the longer term.