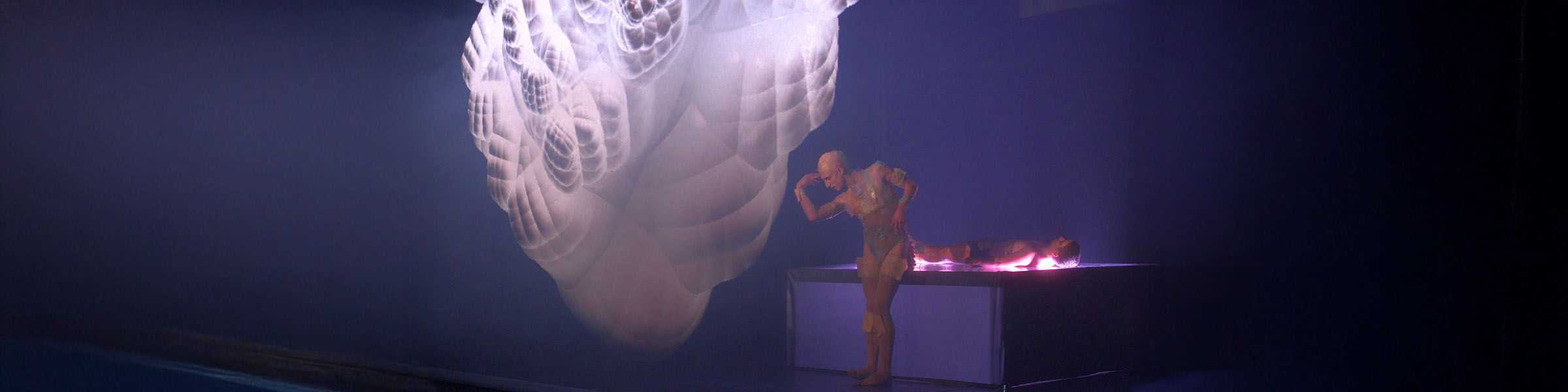

In September 2025, a stage performance with a difference took place at Porto’s Coliseum theatre in northern Portugal. In Re-embodied Machine, a dancer wearing motion sensors interacted with lights and sound that responded to his movements as he whirled across the stage.

The live performance, which used AI, was watched in person by more than 300 people. It was also captured in real time and transmitted via virtual reality (VR) streaming to 200 online viewers, who saw an avatar mirroring the performance in a 3D reconstruction of the theatre.

The experiment offered a small glimpse into how digital tools are reshaping live art.

Positive feedback

The results give reason for optimism about using emerging technologies in the performing arts, said Dr Vassilis Katsouros, director of the Institute for Language and Speech Processing at IT research and innovation organisation ATHENA in Athens, Greece.

“

We achieved a VR transmission in a real setting with spectators.

“We received enthusiastic comments from the live audience and even from people who tried the VR,” he said. “Although there were limitations, and it wasn’t a perfect replica of the physical performance, we achieved a VR transmission in a real setting with spectators. The technology is now there to start finding the right ingredients.”

Re-embodied Machine marked the culmination of a three-year EU-funded initiative called PREMIERE, led by Katsouros and involving cultural and research organisations in Cyprus, France, Greece, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. These included technology research centres, theatre and dance companies, performance venues, arts universities and archives.

The PREMIERE team explored how technologies such as AI and VR can interact with the performing arts. They developed tools to support these kinds of interaction and expand remote access to shows.

Multidisciplinary performance

As audiences fill up theatres in the future, such innovations may lend a spectacular new edge to productions.

“The PREMIERE project explored very interesting use cases where we could see how these technologies are performing in real life,” said Katsouros.

Alongside live performances, another strand of the initiative tested VR rehearsals between remotely located performers in a virtual theatre. The quality of interaction exceeded expectations.

“The actors were impressed by the usability of the VR headsets, which captured facial expressions so they could properly interact,” said Dr Aggelos Gkiokas, an AI researcher at ATHENA who is also an amateur dancer and co-coordinator of PREMIERE along with Katsouros.

“When two actors hugged each other in one virtual rehearsal, they described it as a really emotional moment.”

Gkiokas said the performing arts offer a strong research foundation for developing advanced digital tools for wider use.

“In both theatre and dance, we find facial and language expressions that are outside the norm,” he said. “That makes such performances a good training environment for AI algorithms to understand and replicate extreme expressions that machines cannot capture today.”

Creative potential

Such technologies, he added, create opportunities not possible today – from interacting with imaginary characters to adding visual and audio effects that are not currently feasible. They can also improve access for those unable to attend performances for geographical or health reasons.

“

Technology developments in the performing arts could be applied to human relations in virtual spaces in general.

They also offer audiences the chance to view the stage from different angles and zoom in, or even play a more interactive role in new types of performance.

Beyond the live experience, the project team explored how digital tools could deepen understanding of past performances. Another strand added functions such as 3D visualisation and automatic subtitling to archive footage, allowing artistic directors, researchers and actors to view and study it in a new light.

For actors and dancers, the work during PREMIERE highlighted the value of closer collaboration with technology to understand what is possible and open new opportunities for co-creation.

“One of the project’s most interesting outcomes was that it created a common language between the two separate worlds of the performing arts and technology,” said Dr Kleanthis Neokleous, who leads the immersive technologies group at the CYENS Centre of Excellence in Nicosia, Cyprus – which is also involved in the PREMIERE project.

Beyond the stage

Neokleous said the cultural and creative industries have become a key area for exploring AI and VR at CYENS, with performing arts groups both in Cyprus and elsewhere in Europe now approaching the centre to discuss collaboration.

He also explained that the arts can provide a valuable research testbed for applying advanced technologies to other areas of life, helping to humanise them by improving the realism of emotions and expressions.

“Because of the complexity, level of detail and deep communication required when people perform, technology developments in the performing arts could be applied to human relations in virtual spaces in general,” said Neokleous. “That could be something as simple as a virtual interaction with my doctor, for example.”

While the PREMIERE team made significant progress, the researchers noted that integrating AI, VR and performing arts remains hugely complex. They cited issues such as limited avatar resolution during the live performance, the high cost of motion capture systems and dizziness experienced by actors during extended VR rehearsals.

There are also ethical concerns, including the potential for technology to overshadow traditional artistic practices. The team pointed to risks such as excluding those without digital access or skills, as well as current software biases towards Western styles of movement and dance.

Nevertheless, they said technologies such as AI are still at an early stage of exploration for use on stage and are likely to mature over the next 5 to 10 years, by which time a new generation of artists will be ready to adopt them.

“We understood the current limitations, but we’re here to continue working on new projects and pushing state-of-the-art technologies,” said Gkiokas.

For Katsouros and his colleagues, their experimental work showed that technology can enhance, rather than replace, the shared emotion that makes live performance so powerful.

Research in this article was funded by the EU’s Horizon Programme. The views of the interviewees don’t necessarily reflect those of the European Commission. If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.