Researchers have brought to light the names and quantity of Jews aided by Catholic institutions in Nazi-occupied Rome, Italy during the Second World War, the New York Times reported on Thursday.

The researchers were careful to note that while the study of the documents revealed significant information regarding the specific individuals who were in hiding and those institutions that harbored them, it doesn’t change the scholarly understanding of the role and complicity of the Catholic church and the wider Catholic world in the actions taken by Germany’s Nazi regime.

The documents, which were initially discovered fifteen years ago but only recently studied, helped to elucidate what scholars already knew: some Catholic institutions provided shelter to tens of thousands of people, including thousands of Jews.

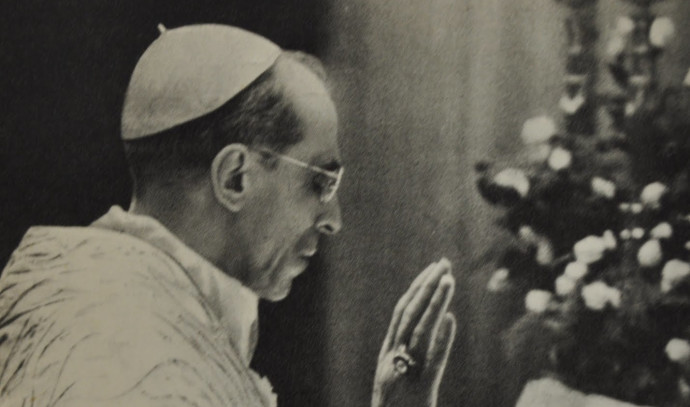

“Now we have specific names and numbers, so, from the historiographical point of view, it’s clearly a great satisfaction,” Liliana Picciotto, a historian at the CDEC Foundation told the New York Times. “But it doesn’t change the historical judgment [of Pope Pius XII,] which remains harsh.”

The CDEC, according to its website, is an independent research institute that works to promote and study the culture and lives of Italian Jews.

The New York Times article relates the damning inaction and complicity of Pope Pius XII, the Pope at the time.

The Catholic Church as a whole was hostile to Jews

Historians have well understood that Pope Pius XII “never called on the Catholic institutions in Rome to shelter Jews during the German occupation and, while he was aware that it was happening,” Brown University professor, David Kertzer said to the New York Times. Further, Pius was “quite nervous about it, not wanting to antagonize the German authorities [and] certainly did not want Jews concealed in Vatican City, and very few were,” Kertzer explained.

Kertzer is one of the researchers who examined the materials acquired from the Vatican’s archives on Pope Pius after Pope Francis opened them in 2019.

While the names of the people identified by the recently studied documents have not been released for privacy reasons, the researchers revealed that the documents highlighted 4,300 people who were given shelter by 155 convents and monasteries.

They were kept in hiding over the course of the Nazi occupation, itself lasting for nine months.

North of 3,200 of the individuals named in the documents were of Jewish origin.

The New York Times noted that Renzo de Felice, an Italian historian, had previously published a list of the Catholic institutions in Rome that had sheltered Jews at the time, but as professor of Hebrew Bible studies at the University of Innsbruck in Austria and the Pontifical Biblical Institute, Rev. Dominik Markl explained, “the entire documentation had been considered lost.”

Rev. Markl went on to explain the significance of the recent study of the documents.

“The value consists in the many names. It’s a wealth of detailed historical knowledge for historians who deal with the research on this period,” Markl told the New York Times over the phone. Additionally, Markl added, that the focus of the conversation surrounding the revelations of the documents should be “on the fate of the many who were persecuted, and those who helped them to survive” rather than on Pope Pius.