The cyberattack that has targeted Marks & Spencer’s (M&S) is the latest in a growing wave of cases involving something called sim-swap fraud. While the full technical details remain under investigation, a report in the Times suggests that cyber attackers used this method to access M&S internal systems, possibly by taking control of an employee’s mobile number and convincing IT staff to reset critical login credentials.

Sim-swap fraud is not a new phenomenon, but it is becoming increasingly dangerous

and more prevalent. According to CIFAS, the UK’s national fraud prevention service, Sim-swap incidents have surged from under 300 in 2022 to almost 3,000 in 2023. What had been mainly a risk to cryptocurrency investors or online influencers is now much more prevalent.

This form of cyberattack shows how major companies and ordinary people can be compromised through a tactic that exploits human factors, such as trust and how we have built our digital identities around mobile phones.

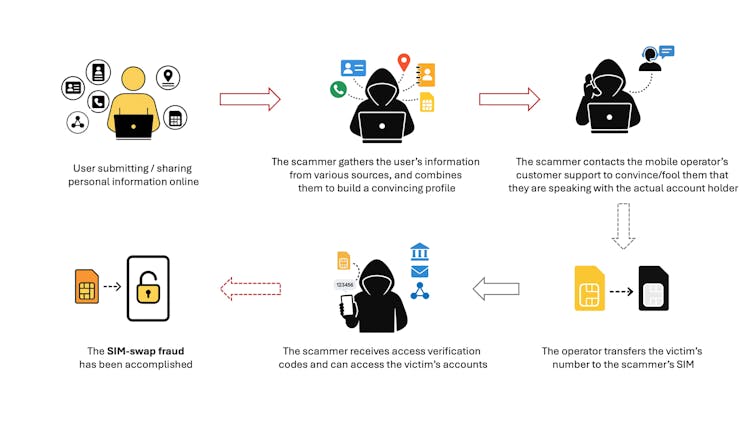

Sim-swap fraud begins when a scammer convinces a mobile operator to transfer a victim’s number to a new sim card, or even an esim (one that’s embedded in the device), under the scammer’s control.

This can be done over the phone, through an online chat, or even with the help of a

bribed insider. Once the number is transferred, all calls and texts intended for the victim are redirected to the scammer. This includes those crucial verification codes used for logging into email, banking, messaging apps such as WhatsApp, and government services such as HMRC.

This alone would be dangerous. But what makes sim-swap fraud so influential is

that the cyber scammer often already has access to a patchwork of personal data

about their target. That information may have been collected from data breaches,

phishing attacks, low-reputation websites, or even the victim’s social media.

People often underestimate the extent to which they reveal themselves online: a birthday posted on Instagram, a phone number included in a job posting, or a home address used in an online giveaway. Scammers combine this data to build a convincing profile, enough to fool a mobile operator’s customer service staff into believing they’re talking to the real account holder.

How the sim-swap fraud works

Once the scammer gains control of a number, the consequences are extensive.

Attackers can access sensitive information, including personal documents and

request and receive password reset links for the user’s other accounts. They can log in to WhatsApp or Telegram accounts, read private messages, impersonate the user, and even contact friends or family members to conduct further scams.

The victims might see false messages posted in their names or fraudulent transactions made from their accounts. This can lead to financial loss, reputation damage, as well as emotional and mental health issues on the part of the victims.

In the case of M&S, attackers apparently used this access to manipulate internal

processes and gain access to sensitive systems. This highlights a broader risk:

many companies still rely on phone numbers as a secondary verification method for

staff, making their systems vulnerable to the same cyberattack used against

individuals.

Hossein Abroshan

Reducing the risk

While real-time detection of mobile number hijacking remains difficult, taking specific steps can significantly reduce the likelihood of being targeted and victimised. People should avoid sharing personal data unnecessarily, especially across multiple platforms and, very importantly, on unknown or untrusted websites.

Many attackers don’t obtain all the necessary information from a single source. Instead, they collect it incrementally, using public profiles, marketing databases and past leaks to form a comprehensive picture.

Being mindful of where you share your phone number, birthday or other identifiers can make it harder for others to impersonate you. It is also crucial to learn how phishing works and how to recognise it, so you will not submit your sensitive information to phishing or fake websites.

Avoiding SMS-based authentication, where possible, is another key step. Many

services now support authenticator apps, such as Google Authenticator, Microsoft Authenticator, Due or Authy, which are not tied to your mobile number. For mobile

accounts themselves, setting up a unique pin or password to your account, which

must be provided to authorise any changes, can add an extra layer of protection. This makes it harder for someone to initiate a sim swap without that code. However, users alone cannot fulfil this duty.

Mobile network operators must strengthen identity verification practices, moving beyond basic questions about names and addresses that can be easily gathered or guessed. Banks and other financial institutions should reconsider using SMS or, at the very least, SMS-only as the default method for sensitive authentication. And companies, particularly those handling personal data or financial assets, need to train their IT and customer service teams to recognise the signs of identity based attacks.

Sim-swap fraud is effective not because it’s highly technical, but because it exploits our trust in phone numbers for identity verification. The M&S case and similar examples show how fragile that trust can be – and why securing our mobile identities is no longer optional.