- Islamist armed groups have carried out widespread killings, rapes, and lootings of villages in northeast Mali since January 2023 forcing thousands of people to flee.

- Security has deteriorated sharply amid clashes between two armed Islamist groups as they seek to control supply routes and increase their influence. The UN peacekeepers’ departure makes things worse.

- The Malian authorities need to ramp up efforts to protect civilians and work closely with international partners to ensure that displaced people have access to aid and basic services.

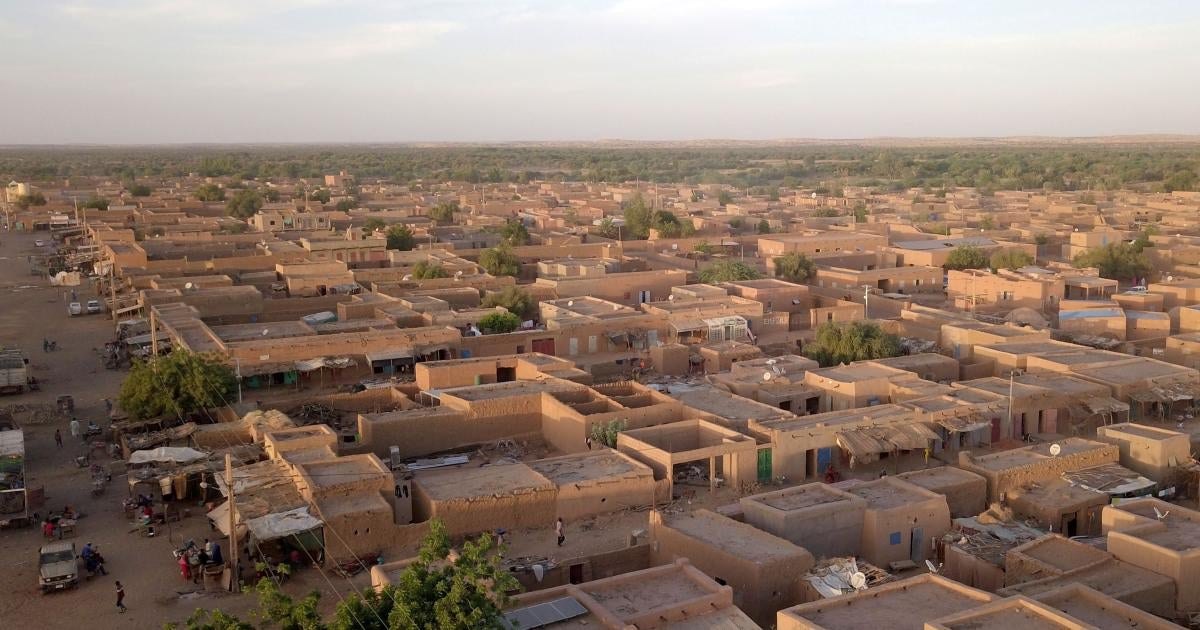

(Nairobi) – Islamist armed groups have carried out widespread killings, rapes, and lootings of villages in northeast Mali since January 2023, Human Rights Watch said today. Thousands of people have been forced to flee Ménaka and Gao regions.

Amid the mounting abuses, Mali’s transitional military government obtained United Nations Security Council approval for the departure of the UN peacekeeping force, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), beginning July 1. The Malian authorities will need to work more closely with regional bodies and donor governments to address the expanding security and aid vacuum.

“Islamist armed groups are brutally attacking civilians and fueling a massive humanitarian emergency,” said Ilaria Allegrozzi, senior Sahel researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The departure of UN peacekeepers means that the Malian authorities need to ramp up efforts to protect civilians and work closely with international partners to ensure that displaced people have access to aid and basic services.”

Between March 1 and July 11, Human Rights Watch interviewed by telephone 52 people with knowledge of attacks on villages by Islamist armed groups. They included 39 witnesses to abuses, 7 members of Malian civil society organizations, and 6 representatives of international organizations.

Security in Ménaka and Gao regions has deteriorated sharply amid clashes between the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and the rival Al-Qaeda-linked Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa al-Muslimeen, JNIM), as both Islamist armed groups seek to control supply routes and increase their areas of influence. The UN reports that fighting across Mali has forced 375,539 people from their homes, 40 percent of whom are located in the Gao, Kidal, Ménaka, and Timbuktu regions, resulting in one of the worst humanitarian crises in recent years. The two groups use a strategy of displacement to demonstrate their power and impose their authority in Mali and neighboring Burkina Faso.

Human Rights Watch documented eight attacks between January and June: six in Gao region and two in Ménaka region. Witnesses provided consistent accounts of the methods used in the attacks and similar descriptions of the attackers. ISGS fighters were armed with Kalashnikov-style assault rifles and sometimes rocket propelled grenade launchers, rode motorbikes and pickup trucks, and were dressed in civilian clothes or military fatigues with identifiable turbans. Human Rights Watch received information about five more attacks in both regions that could not be corroborated but that matched accounts of other Islamist armed groups’ attacks.

Witnesses said the fighters spoke the local languages of Tamashek, Fulfulde, Songhai, and Hausa, as well as Arabic, and sometimes carried the Islamic State flag, which usually consists of a black background with the Shahada [Islamic profession of faith] text in white. Residents said that the fighters stormed their villages, shooting, looting, burning, destroying property, and in many cases warning people to leave the area.

“They rounded up the whole village and gave us three days to leave,” said a 50-year-old man from Essaylal village in Ménaka. “They said: ‘If we find anyone around after three days, we will kill everyone.’ And that’s why I decided to flee.”

A man from Bourra, Gao region, said that in February the Islamic State-linked fighters threatened him with death if he did not give them his 15-year-old daughter for marriage: “Two fighters came to my house .… [T]hey wanted my daughter. I refused and so … they said I could be executed for refusing to grant a marriage.”

Human Rights Watch could not confirm the total death toll from the attacks in Ménaka and Gao regions since January. Accounts by aid workers and witnesses to abuses suggest that hundreds of civilians have been killed since January and tens of thousands forced to flee, having lost their livestock, livelihoods, and valuables during the attacks. “Since January, we have recorded over 100 civilians killed [by ISGS] in several villages around Ansongo [Gao region] and scores missing,” said a humanitarian worker based in Ménaka region. “Looting, targeted killings, [and] kidnappings sometimes followed by demands of ransom … Islamic State fighters have no mercy for the population.”

In early 2022, Human Rights Watch documented a similar pattern of abuse in the same regions, with fighters linked to each of the two groups killing hundreds of civilians and forcing tens of thousands to flee in attacks that appeared systematic and coordinated.

Both the Malian army and MINUSMA had forces in the cities of Gao, Ménaka, and Ansongo. In contrast to their actions in central Mali, however, these troops have conducted limited patrols, with little capacity to protect civilians outside urban centers. The authorities’ presence is also very limited in rural areas in northeastern Mali.

In a June 26 interview with the Russian media outlet RT, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that members of the Wagner Group, a Russian private security company sponsored by Yevgeny Prigozhin, were in Mali, “working there as instructors.” The Wagner Group has been implicated in atrocities in several African countries, including Mali and Ukraine.

Human Rights Watch has also documented serious abuses by the Malian security forces and apparent Wagner forces during counterinsurgency operations in central Mali.

In addition to the impact on security in Mali, the MINUSMA pullout could harm efforts toward accountability for conflict-related abuses, Human Rights Watch said, as the mission’s mandate included monitoring and reporting on human rights abuses in Mali. Malian authorities should continue to work with the UN Human Rights Office and the UN’s independent expert on human rights in Mali, Alioune Tine.

In February, the Malian government and aid groups in Mali issued a 2023 response plan with an appeal for US$751 million to meet the urgent needs of 5.7 million people. However, as of June the plan remained severely underfunded “with over 80 per cent of the food security needs unmet,” despite the “deterioration in the humanitarian situation.” MINUSMA’s departure could also worsen this precarious humanitarian situation, as the mission facilitated access to conflict-affected areas, including the town of Ménaka, for aid groups.

Experts from the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the Economic Community of West African States should focus more on the human rights situation in Mali, and press Malian authorities to allow them to work with Mali’s National Human Rights Commission to monitor and report on human rights abuses, Human Rights Watch said.

“Mali’s international partners should step up efforts to support the humanitarian response plan and work with Malian authorities to ensure greater humanitarian assistance to all people in need,” Allegrozzi said.

For detailed accounts of the abuses and other details, please see below. The names of those interviewed have been withheld for their protection.

Islamist Armed Group Abuses in Northeast Mali since January 2023

On June 16, Mali’s transitional military government called on the UN Security Council to immediately withdraw MINUSMA, alleging a “crisis of confidence” between the Malian authorities and the UN peacekeeping mission. On June 28, the Security Council voted to terminate MINUSMA’s mandate and remove the mission’s 15,000 armed and civilian personnel, to be completed by December 31.

This followed France’s announcement in February 2022 to end its nine-year military operation in Mali, which at its peak included over 5,000 troops. France completed the withdrawal in August 2022.

Killings, Forced Marriage, Beatings, Looting in Gao

Konga

In February, men armed with Kalashnikov-style assault rifles and riding motorbikes, whom two witnesses identified as ISGS fighters, came to Konga, a settlement in the village of Kounsoum, searching for a man they accused of collaborating with the Malian army. “They didn’t find him, and in retaliation, they killed his two wives,” a 63-years-old man said.

A 49-year-old man said:

From my hiding place, I saw two fighters entering the courtyard [where the two women were]. I heard them speaking in Fulfulde and Tamashek and asking the women: “Where is your husband?” The women replied that they didn’t know … and then I heard gunshots and saw the women falling to the ground.

The man added that, when he left his hiding place, he found that the women had been “both shot in the head.”

The witnesses, who both fled to Ansongo after the attack, said that the fighters also gave an ultimatum to villagers ordering them to clear the area. “They gave us 24 hours to leave,” one said. They said that after that, if they found someone around, they would exterminate everyone.”

Bourra

Two men said they fled Bourra with their families to Ansongo, one in February and the other in May, following repeated threats, looting, and harassment by ISGS fighters. They said that since 2022, the group’s fighters have “raped our women” and imposed Sharia (Islamic law) on their village, requiring them to pay zakat [religious tax] and adhere to strict morality and dress codes.

A 70-year-old man said the ISGS fighters “took 47 cows from me … my motorcycle and my son’s motorcycle.” He said that the fighters rape women:

We call it rape because if they like a woman in the village, they kidnap her and force her to sleep with them. To justify this rape, they tell us that it is a marriage .… If they don’t want the woman anymore, they release her and say she has been divorced .… But where is the marriage without consent? Another system they use is that if they ask for your daughter in marriage, you have to give her against your will, under threat, and then if the fighter no longer wants her, he passes her to another fighter … a system of gang rape disguised as marriage. We have been suffering this shame .… [N]o one talks about it, the subject is taboo, if you talk about it, the jihadists will find you wherever you are, and they will even kill you.

The man said he was forced to flee to Ansongo in May, “to escape this constant harassment and find some security.”

A 67-year-old herder said he fled Bourra after two ISGS fighters attempted to take his 15-year-old daughter in February:

One night, two fighters came to my house with weapons and told me that I must give them my daughter for marriage .… I told them that she will marry a man she would love. They replied that a girl has no choice in marriage. They told me that I am stubborn, and if I ever continue in this bellicose tone, I could be executed for refusing to grant a marriage. Taking advantage of our conversation, my wife took my daughter and ran away with her. They [fighters] looked everywhere and did not find her and came back to tell me that if I do not give the girl I will be killed. That’s why I fled. Many parents have seen their daughters married off without their consent.

Tannal Koyratadji

On the evening of April 23, armed men with Kalashnikov-style assault rifles and rocket propelled grenade launchers, whom two witnesses identified as ISGS fighters by the black flag they carried and the red bands around their heads, entered the village of Tannal Koyratadji. They killed two older men, injured at least seven men, and looted food and livestock, the witnesses said.

A 54-year-old farmer said:

Before the attack, we received a message on WhatsApp by a person who claimed to be a jihadist saying that we [villagers] side with the Malian army and with Wagner and that if we don’t leave the village, we would be considered as informants and killed. So, many fled .… The day of the attack I saw the fighters coming aboard 10 motorbikes, heavily armed, two on each motorbike .… I hid and heard shooting, then I saw lots of dust because they made our animals flee.

A 41-year-old man said:

They killed two older men and injured others because of the indiscriminate shooting .… They looted the whole village. They took our cows, donkeys, goats, they took our millet and rice. After the burial, I fled the village with my family.

Both witnesses provided identifying details of the two victims, both over the age of 60. Both said they left the village after the attack and sought refuge in Ansongo.

Labbezanga

In early May, ISGS fighters armed with Kalashnikov-style assault rifles led two consecutive attacks on the village of Labezzanga, an coastal village along the Niger River, three witnesses said. They said that some of the fighters were in civilian clothes and others in military fatigues with body armor, and carrying the Islamic State flag, There, they killed four men and injured another, and looted livestock.

A 60-year-old man said:

The first time, they [fighters] took our cows, and left screaming, “Allahu Akbar [God is Great]!” The second time, they killed four villagers who refused to let them take [their] animals away. For us, the cow is like our life, if you take it from us, it’s like you have taken our life away .… Three villagers were killed when they chased the assailants and begged them to return the animals. The fourth man was killed [by fighters] in his house and his son was injured by a bullet for having encouraged other villagers not to accept the looting of animals.

A 39-year-old man said that the day following the second attack, “We found the bodies of the three villagers who bravely chased the assailants some two kilometers away from the village.” The man said that the bodies were riddled by bullets, two lying on their back and another on their side:

We covered the bodies with a cloth and took them to the village health center, where a doctor said they had been shot in the chest, in the stomach, and in the head. And then we buried them in the cemetery alongside the body of another man who had been killed during the attack.”

The witnesses provided identifying details of the four male victims, ages 32, 40, 50, and 70.

Seyna Gourma

On May 20 and 23, armed men with Kalashnikov-style assault rifles, whom two witnesses identified as ISGS fighters by the red bands around their turbans, attacked the village of Seyna Gourma. On May 20 they looted livestock. Three days later they went door to door, searched homes, beat villagers, and again looted livestock.

“When they [fighters] came the first time, I fled to the bush and returned the following day,” a 44-year-old woman said. “When they came back [on May 23], they found me in my house and beat me in front of my children, who are now traumatized. They broke into many homes and beat people savagely, men and women.”

The woman, a widow, said she was too frightened to stay and “had no other choice” but to flee to the town of Ansongo, where she is struggling to survive: “I am very anxious. I lost my husband and do not have any property that could interest them [fighters] … So why attack me? I used to do small farming and now that I am displaced, I cannot harvest the fruits of my labor.”

A 45-year-old man, who also fled to Ansongo after the second attack, said:

During the first attack, I wasn’t around, but they [fighters] took five of my bulls, which I was supposed to sell .… During the second attack, I was beaten by two jihadists [Islamist fighters] who spoke Fulfulde. They beat me with the butts of their guns. They hit me twice in the ribs and elsewhere, and I lost consciousness. I’m not the only one who was beaten that day, they beat everyone. I suffered injuries to my arm and ribs.

The man said he was treated at a health center in Ansongo. He described living under the Islamic State:

They veiled our women and prevented them from going about their business. They asked us to pay the zakat. They beat and threatened us. There are no reasons for these attacks. It is to terrorize us, to impose their law and prevent us from reacting while they loot our animals and steal our property.

Dangabari and Gaina

On June 27, scores of ISGS fighters attacked Dangabari, Gaina, and other villages in Gabero municipality, killing at least nine men and two boys in Dangabari and four men in Gaina, and looting livestock, seven witnesses said. Residents also compiled three lists of the people killed, who ranged in age from 15 to 50.

Witnesses believed the attack was in retaliation for the beating death of an injured ISGS fighter by villagers in Boya, a village near Dangabari, on June 21.

Witnesses said that fighters, some dressed in civilian clothes and others in military fatigues with body armor, surrounded Dangabari and Gaina, shooting indiscriminately and breaking into homes, summarily executing people or shooting them as they ran for cover.

A 50-year-old woman from Dangabari whose two sons, ages 20 and 23, were executed during the attack, said:

I heard the first gunshots at around 3 p.m. Then, the village was invaded by armed men who shot everywhere screaming “Allah Akbhar!” I didn’t move. I sat in front of my door. Two fighters came and one pointed his gun at my chest, he was so close that he touched me, he told me in Songhai: “Tell me where the men are, or I will kill you.” But the other fighter said in Fulfulde “warga, warga” which means “leave her, and let’s go.” That’s how I was spared .… When the fighters left, villagers informed me that my two sons and another man had been executed just outside the village, shot in the head. Our traditions do not allow women to see the bodies, so my relatives went to collect the bodies and buried them.

A 46-year-old man from Dangabari who helped with the burial of five bodies, including those of the two brothers, said:

We found the bodies of three men, including two brothers, at about a kilometer from the village. They were lying face to the ground, side by side. They had been shot in the head, back and bottom .… We wrapped them in clothes and buried them in the nearby village of Monia. There, we also buried two more bodies of two men who had been killed in their homes in the village [of Dangabari]. These two men had also been shot in the head. One of them, his head, was destroyed. We dug a big hole and inside it we made five individual graves.

A 45-year-old man from Dangabari said:

At around 4 pm, a horde of terrorists riding motorcycles surrounded our villages [of Dangabari and Gaina] and blocked all ways in and out. They shot at everything that moved … I hid under my bed … Two fighters came to my place, and one asked my wife in Songhai: ‘Where is your man?’ She replied: “My man is in the bush.” So, he said: “We will be searching your house, if we find him, we will kill you first and then your man.” But likely the other fighter who spoke Fulfulde said: “Leave her, don’t go inside.” When they left, they stole my two sheep.

A man from Gaina whose 30-year-old brother was killed in the attack said:

They [fighters] came on motorbikes, two on each motorbike. They rode very fast and shot everywhere, they shot at people who tried to flee .… I hid behind a house, but my brother did not want to come with me because he believed the place was not safe … From my hiding place, I saw a motorbike with two fighters following my brother who was running. The one [fighter] sitting in the back opened fire at my brother and he fell dead on the ground.

A 34-year-old man who helped with burying the bodies of the men killed in Gaina said:

We found four bodies. One was shot everywhere, particularly in the back, as he tried to escape. Another body of a 41-year-old man was also lying in the street, he was shot in the back and bottom. The third one was shot in the head, the fourth one, his arms were broken, the chest was swollen, and he had the mark of a bullet in his head. We buried three of them in the cemetery of the nearby village of Soungai, while the fourth was buried by his parents in the village of Fétéyoro.

Threats, Forced Displacement, Property Destruction in Ménaka

The attacks documented in Ménaka region have largely targeted Dawsahak people, members of a Tuareg ethnic group whom Islamic State fighters accuse of collaborating with JNIM. The Dawsahak militia, known as the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (Mouvement pour le salut de l’Azawad, MSA-D), allied with the Malian government since a 2015 peace agreement, has carried out attacks against ISGS in Mali’s northeast, at times reportedly siding with JNIM.

“I fled in March [to Ménaka town] before the arrival of the Islamic State fighters,” said a 48-year-old man from the village of Ikadewen, Ménaka region. “If they found us in the village, they would exterminate us, because we were controlled by JNIM before they took over and they consider all Dawsahak as JNIM collaborators or members of the [Dawsahak militia].”

The UN has reported that 78,500 people had been displaced in Ménaka center between March 2022 and the first trimester of 2023, and over 10,700 more between April and May.

Teguerert

In January, an armed clash between ISGS and JNIM fighters for control of territory near the village of Teguerert, largely populated by ethnic Dawsahak people, led to the burning of some houses in the village and massive displacement of the local population, two witnesses said.

A 25-year-old shop owner said:

The confrontation started early in the morning, in the bush. We heard gunshots and detonations. At about 11 a.m., the shooting got closer, as if the fighting was coming towards us .… When the fighting ended with the victory for the Islamic State, their fighters came to our village, burned homes and looted everything. My shop was ransacked first and then set on fire. Everyone fled to different locations, to Gao, to Kidal, to Ménaka town.

A 36-year-old herder said:

We are mostly ethnic Dawsahak here and we have been targeted for a long time .… After this heavy fighting, we had no choice but to leave, in order not to suffer abuses … because in Ménaka [region] civilians are trapped; either they are accused by the Islamic State fighters of collaborating with the Dawsahak militia and the army … and punished for it, or they are caught in clashes between the two rival terrorist groups.

The witnesses said the confrontation resulted in the death of more than 40 fighters from both groups, as well as in “dozens of wounded civilians.” Both left Teguerert to seek shelter and protection in Ménaka.

Essaylal

In March, Islamic State fighters armed with Kalashnikov-style assault rifles and rocket propelled grenade launchers arrived on 10 motorbikes in the village of Essaylal, mostly populated by ethnic Dawsahak people, and issued an ultimatum for the population to leave the area within three days, several witnesses said. The fighters, who wore military fatigues or civilian clothes and bulletproof vests, arrived after a Malian armed forces patrol had passed through the village.

A 39-year-old man said:

They [fighters] accused us of collaborating with FAMa [Malian Armed Forces] .… They rounded up the whole village and said that we side with FAMa and the MSA .… They said: “Here we make the rules, either you accept, or you are dead.” They said if they found anyone in the village at the end of the ultimatum [period], they would kill him.

The man said he fled with all his family on the second day to Ménaka town where “we need everything, lack humanitarian assistance,” and “we live with 11 other families in the same courtyard.”

Another man, who also fled to Ménaka town following the ultimatum, said: “They [fighters] came, they threatened the whole village and ordered us to clear the area. I left in a hurry with my wife and children, I had to leave everything behind .… In Ménaka we live in miserable conditions.”

Everyone interviewed said that they fled their village after the ultimatum and that they are currently displaced in Ménaka town where they “face many challenges to survive,” as one said, and “are in desperate need of humanitarian assistance.”

Attacks in Other Regions

JNIM and ISGS fighters have also killed civilians in other parts of Mali during 2023, as well as Malian soldiers, government officials, and MINUSMA peacekeepers. Human Rights Watch investigated an April 22 attack in Sévaré, Mopti region, claimed by JNIM, that left at least 10 civilians dead and 60 injured, as well as more than 20 buildings destroyed. On April 21, JNIM also claimed responsibility for an attack on April 18 which killed the chief of staff of Mali’s interim president, Oumar Traoré, and three others in Nara in Koulikoro region.

Sévaré, Mopti Region

Early in the morning of April 22, an attack targeting the airport and a military camp in the town of Sévaré resulted in a large explosion that killed at least 10 civilians, injured 60 others, and destroyed more than 20 buildings. On April 25, JNIM claimed responsibility for the attack. Even if the attack was on a valid military target, it appeared to be unlawfully indiscriminate and was most likely disproportionate, causing greater civilian harm than any anticipated military gain.

Human Rights Watch spoke to five witnesses, including two who were injured:

A 46-year-old mechanic said:

That night we slept outside because of the heat. At about 5:30 a.m., we were awakened by a loud noise. We didn’t understand anything. Pieces of brick fell onto us. I was injured in the head, my wife in the arms, my children in the legs. Our home collapsed. We were lucky, but the families living on the other side of the road were not. The Karambe family, for example … all their four children died in the explosion … their house collapsed on top of them.

A carpenter who said he was about 900 meters from where the explosion occurred said:

I was riding my motorbike. Suddenly I heard a loud noise, then a “boom!” The earth rumbled, and I fell on the ground, unconscious. When I woke up, there was dark smoke all around and I was coughing. I went home, and only went back to the area of the explosion around noon. I found that all the houses within a 200-meter radius had been destroyed. An entire family was crushed by the blast, there was no trace of their house. I went to Somino Dolo hospital to meet the wounded and many had suffered fractures because their homes had collapsed [onto them].

In an April 22 communiqué, Col. Abdoulaye Maïga, the spokesperson for the Malian transitional military government, said that Malian armed forces killed “terrorists” carrying out a “complex attack” with “car bombs” targeting the Sévaré airport.

In its April 25 statement, JNIM accused the Malian army of killing civilians in a drone strike that targeted one of the suicide vehicles. Human Rights Watch could not confirm these claims.

A 40-year-old witness said:

It’s hard to say if the army reacted quickly or not. We were terrified by the sounds of the explosions, and what I do know is that first there were the detonations and then shooting started at about 6 a.m. until 7 a.m. … we heard shooting everywhere.