But the party is unlikely to last.

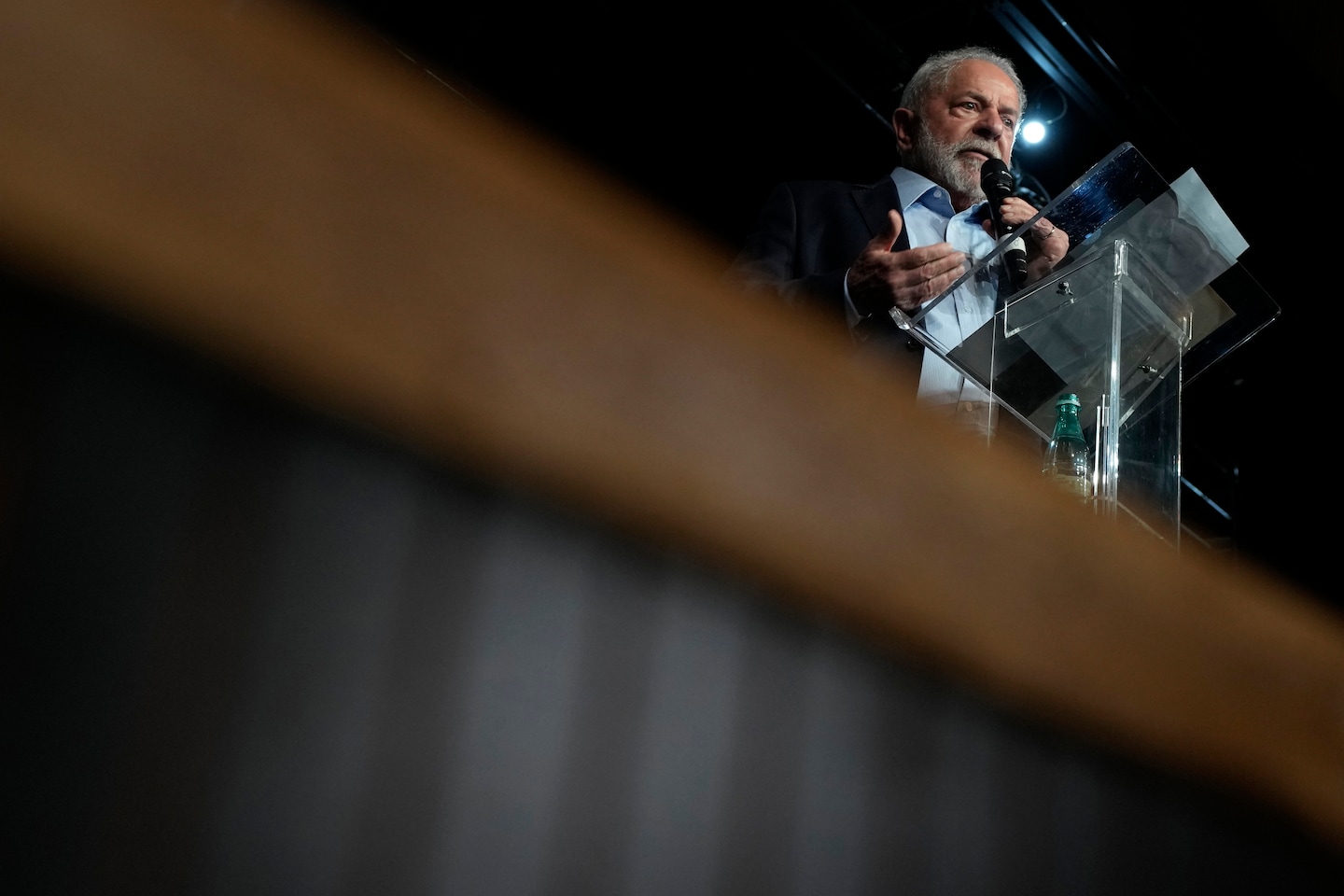

Lula, 77, defied history in October to win a third term as president just three years after exiting a jail cell. But now he’s facing a greater challenge: How to govern a country divided, plug fiscal holes, and make good on a host of politically difficult campaign pledges: Protecting the Amazon jungle, tackling police brutality, and toughening the gun laws that were relaxed by his predecessor, Donald Trump ally Jair Bolsonaro.

He’ll be trying to do it in a political atmosphere familiar to Americans. Bolsonaro, who lost the election in October, has allowed a transition, but he has yet to actually concede — a refusal that has encouraged his core supporters to refute the legitimacy of a Lula presidency. Thousands of them remain camped out at army barracks across the country, calling for a military overthrow of the incoming government. Weeks before the inauguration, violent Bolsonaristas attacked police and burned buses in Brasilia. Raids in eight states soon after yielded weapons and arrests for alleged “anti-democratic acts.”

This is “a reminder of the significant share of Brazilians who are deeply opposed and hostile to the Lula administration,” said Robert Muggah, co-founder of the Rio think tank Igarapé Institute. “The risk is that they could be mobilized in a more substantial way in the coming year should the incoming administration make any significant missteps.”

The political dynamics in Latin America’s largest nation are sharply different from 2003, when Lula first took office. Conservative then-president Fernando Henrique Cardoso, graceful in defeat, warmly handed over the presidential sash — a ceremonial affirmation of democracy that Bolsonaro has yet to confirm he’ll perform on Jan. 1.

Perhaps more importantly, the economic dynamics are different, too. During his first term, Lula benefited from a global commodities boom and rising trade with China — cash cows that enabled him to finance massively successful poverty-busting social programs, maintain business-friendly policies and coast to a second term with broad support in 2007. He left office after eight years with an approval rating above 80 percent.

Now Brazil is facing economic head winds. Sky-high inflation is easing, but at the cost of elevated interest rates that could dampen investment. Meanwhile, Lula is inheriting a fiscal mess. Under Bolsonaro, limits on fuel, natural gas and electricity surcharges thinned out state, local and federal coffers. A 2000s-style spending spree now would dig the fiscal hole deeper.

Lula’s standing now is also different. After he left office in 2010, he was convicted of corruption and money laundering as part of the international graft scandal involving the Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht. He maintained his innocence, and supporters called the prosecution political persecution. But in 2018, he turned himself him in to begin serving a 12-year sentence, clearing the way for Bolsonaro’s surprise election victory that year.

Nineteen months into Lula’s prison term, the Supreme Court ruled he had been denied due process and ordered him released. The charges against him were annulled last year.

His win now in the closest election in Brazilian history has left him with a weak mandate. He starts his term rejected by millions and with tensions in the country running high. His camp has accused Bolsonaro of being anti-democratic. But moves by the Supreme Court to raid and arrest Bolsonaro’s supporters with little transparency have generated counterclaims of dangerous new limits on free speech.

It has set up a scenario in which millions of Bolsonaro loyalists still believe Lula will not be inaugurated on Jan. 1. They have clung to the belief — dismissed as fantasy by analysts — that the military will block the president-elect from taking power.

“Lula will not be president,” said Marilene Lopes, a 61-year-old bolsonarista who has been camped out in front of the Southeast Military Command Center in São Paulo since Halloween, the day after the election. “He certainly won’t be president.”

Bolsonaro, like Trump, has a limited but devoted base. To defeat him, Lula cobbled together a political coalition in defense of democracy that included politicians whose ideologies differ sharply from those of the traditional leftists within Lula’s Worker’s Party (PT, for its initials in Portuguese). That’s already generating friction — including internal disputes over which non-PT politicians will win top jobs in Lula’s unity government.

Over time, those frictions could become fault lines — a worrying prospect even for a consensus builder as famously adept as Lula, who is widely considered an elder statesmen of the Global South.

“He was elected with a united front,” said Marco Nobre, a political analyst and author. “But it is harder to govern with one.”

Lula plans to move quickly to assert his presidency, undoing of a slew of Bolsonaro’s executive orders and issuing directives that will have global impacts.

Environmentalists around the world have watched aghast as Bolsonaro gutted government agencies meant to protect the Amazon rainforest while allowing the growth of criminal activity — illegal logging, farming and fishing — to go unchecked. That contributed to a 60 percent increase in deforestation during his term. With the Amazon nearing a tipping point, Lula has vowed to reverse the tide.

His advisers say he will restart the Amazon Fund, a Brazilian government initiative to entice foreign donors to help protect the Amazon that stalled under Bolsonaro. Lula’s government will move fast to strengthen remote surveillance, using satellite images to combat illegal deforestation. Teams from IBAMA, Brazil’s chief environmental agency, are planning “full force” operations against environmental crimes in January, according to a person familiar with the situation who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the efforts had not received final approval.

Marcio Astrini, executive secretary of Climate Observatory, a network of Brazilian environmental groups, said criminal lawlessness has become so entrenched in the Amazon that enforcing the law now will be more difficult.

“The biggest difference between Lula’s first two terms and now is how environmental criminals in the Amazon became so powerful and wealthy during Bolsonaro’s government,” Astrini said. “They have much political influence in some municipalities. They can dominate towns from an economic perspective. It is because in some regions of the Amazon, that’s the only opportunity people have.”

Lula’s pick for justice minister, Flavio Dino, has outlined plans to counteract Bolsonaro’s executive decrees that eased rules for gun ownership — measures that tripled the number of registered arms in Brazil to nearly 1.9 million. Dino has said the government will launch a voluntary buyback program and ban the purchase of some automatic weapons.

To push through his agenda, Lula will need to tame Congress, where Bolsonaro’s loyalists outnumber his own. He’ll need to woo centrist and other parties.

Two recent Supreme Court rulings have given Lula more power to bargain with Congress.

One defused a financial bomb left by Bolsonaro. The 2023 budget did not fund welfare payments for millions of poor Brazilians, setting Lula up for an early crisis. Brazil’s unique fiscal caps — written into the constitution to control runaway spending — could have stopped Lula from sourcing more government funds. But the justices gave him the breathing room to do so, allowing a half-victory of sorts: A one-year deal with Congress that will have be renegotiated in 2023.

In the other ruling, the justices took aim at the so-called secret budget that allowed Brazilian lawmakers to divert government resources to their constituencies with little oversight from the executive branch. Lawmakers are maneuvering to claw back some of those powers, but the court appears to have handed Lula more control over spending — and thus over Congress.

One great risk for Lula is that any misstep by his government could trigger Bolsonaro’s loyalists to take the streets in larger numbers, the way waves of Brazilians did in 2013 to protest transit price increases. Those protests, led by the angry middle classes, were seen as critically undermining Lula’s handpicked successor, Dilma Rousseff, who was impeached in 2016.

On Saturday, police in Brasilia arrested a man they said had planted a bomb in a tank trunk full of gas near the international airport. Allies of Lula have told the newspaper Folha they fear new terrorism attempts.

Authorities said the suspect, George Washington de Oliveira of Pará state, told investigators that his plan was to provoke chaos to draw military intervention. He had allegedly camped with bolsonaristas outside army headquarters in the capital.

“The serious events of yesterday in Brasilia prove that such ‘patriotic’ camps have turned into incubators of terrorists,” Flavio Dino, Lula’s pick for justice minister, tweeted on Sunday. “Measures are being taken and will be expanded.”

Also on Sunday, authorities said, a group of Indigenous people invaded a restricted area of the supreme court building to press for the release of Indigenous leader José Acácio Serere Xavante. The court has accused the Bolsonaro supporter of having “expressly summoned armed people to prevent the certification of elected” officials. Ten people were arrested, authorities said.

Bolsonaro and his core loyalists, analysts say, are likely to stoke the culture wars as Trump, Bolsonaro’s political lodestar, has done in the United States, to undermine Lula and to lay the groundwork for a future presidential bid. The outgoing leader could also try to exploit rifts in Brazilian society between the more affluent south, which largely backed him in the election, and the poorer northeast, Lula’s base.

“What Brazil is headed for is a new division, which is regional, far more than it’s been in the past, and which is increasingly polarized between the center-left, which is progressive and committed to democratic values, and a more radical right,” said Matias Spektor, a foreign affairs analyst at the São Paulo-based Getulio Vargas Foundation. “That will make the implementation of progressive policy more difficult.”

Faiola reported from Miami. Duran reported from Bogotá, Colombia.