Carnivores like leopards, lions and hyenas have been killing livestock for centuries, causing financial losses to farmers. In many parts of the world, farmers respond by killing these predators. This has greatly reduced the populations of some top predators like leopards and lions.

Killing predators may decrease their numbers in the short term. But there is no evidence that it is an effective way to protect livestock in the long term. For example, in South Africa, populations of the medium-sized predators like caracals and jackals that also predate on livestock increased or migrated into the area in response to lethal control efforts.

Copyright Cape Leopard Trust

For this reason, farmers in South Africa are looking at non-lethal methods of protecting livestock. One sustainable, wildlife-friendly method is the age-old practice of herding or shepherding.

Very little data exists on how shepherding compares with lethal methods globally or in South Africa. We conducted a study in South Africa to fill this information gap. We found that shepherding was very effective. Using shepherds, livestock losses were five times lower than losses under lethal methods.

Our results suggest that shepherds not only reduce predation; they may also be able to give a clearer picture of what causes livestock deaths. For instance, shepherds can see when livestock deaths are caused by illness rather than predation. This is supported by other research that shows predators may be blamed for livestock deaths that were actually due to exposure, illness or some other cause.

The presence of shepherds could allow for more prompt responses to ill, injured or lost animals. A person who is with livestock all day can also identify where fences and water points are damaged, assess what grazing conditions are like and make decisions about herd movement.

The challenge

Shepherding involves herding and protecting small livestock while moving between grazing areas and water points. Shepherds are also often responsible for corralling animals in a pen at night.

This is not a new strategy. Shepherding has been practised since early pastoralism began about 9,000 years before present (or BP, referring to the 1950s, the date up until carbon dating can be practically used).

But its efficacy is understudied globally. That means there’s little empirical evidence to show whether it’s the best approach to keeping livestock safe, where it might be used along with other methods, or where it might not work at all. Existing data often relies on interviews, with their inherent biases, rather than on observations in the field.

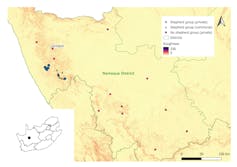

Our study sought to fill this gap. We are researchers in the fields of botany, zoology, agricultural economics and conservation. We set out to quantify livestock losses ascribed to predators in South Africa’s Northern Cape province. The province’s dry climate means that the main agricultural activity is livestock farming.

The Northern Cape has the highest recorded national livestock losses to predation – an average of 13% of the herd.

Our study

We hypothesised that shepherding would be more effective in reducing predation on small livestock (mostly sheep but also goats) relative to other methods. We had access to two databases: one relying on interviews with farmers who had used mostly lethal methods, and one using field observations by shepherds and mobile technology. We consolidated these two databases into one publicly available online database.

Unfortunately, data on predator or prey populations (which can influence predation) were not available for our sites in the Northern Cape.

We confirmed, however, that the livestock types, dominant predators and environmental conditions were similar across the two databases. Using statistical analyses, we tested how predator management (shepherd, no shepherd), land tenure (private, communal), flock characteristics (herd size, livestock type), and environmental factors like terrain and plant productivity drove losses of small livestock across the area.

As we expected, black-backed jackals and caracals were the dominant livestock predators in both management groups (shepherd, no shepherd). Also as predicted, the loss to predation was lower (five times) in shepherded herds than in the no-shepherd group. For lambs only, this was even more obvious with a seven-fold reduction in predation.

Copyright L Minnie

Using herders’ direct observations rather than gathering information from questionnaires also allowed us to quantify livestock loss due to causes other than predation. In our study area, we found that livestock illness caused as many deaths as predation. This was in line with global assessments by the Food and Agriculture Organization that showed losses from disease (30% of a herd) and exposure (anywhere from 9% to 52%) were the main causes of livestock mortality and were several times higher than the global average for predation (5%).

This contrast merits further investigation locally and regionally in Africa so that farmers know where to place their management efforts in the future.

All farmers, whether they were managing land privately or communally, experienced similar predation issues and drivers of predation in our study. This means that shepherding could be scaled to work even for privately owned (and usually large commercial) farms as a means to protect livestock.

Conservation International

Several farmers in the study were keen to use or continue using herders. Others felt there were barriers to their use, such as financial costs and social issues.

The data proved useful to the herders, too. One, Brenda Snyman, said:

Now we have the numbers. We really value the skills we’ve gained in herding and data collection during the study.

Historically, herding has been an unappreciated and poorly paid profession. But with specialised programmes to train herders in animal husbandry and farm management now gaining ground, the skills and profession of herding may soon receive more recognition, while generating rural employment.

The solution

We must interpret our findings with caution because we were unable to account for predator and prey abundances. It is also possible that the non-herder group inflated their predation estimates during interviews. But, given the scarcity of existing information, these are exciting results that can be applied and form a basis for further research. They could also prove useful for decision-making by land users, and in policy change.

Graham Kerley, Liaan Minnie, Dave Balfour, HO de Waal and Walter van Niekerk collaborated in this research. The authors thank Emma Cummings-Krueger (Conservation International) for her help on the text.