It has become quite common to complain nowadays that, given the overall concern for marginalized groups and the claim that social justice should be of interest to anyone, ideology rules science. Some go even as far as comparing the current research system with Lysenkoism, a flawed approach to plant genetics promoted by Soviet and Chinese authorities.

Such as the case with an April 27 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, “The ‘hurtful’ idea of scientific merit”, by scientists Jerry Coyne and Anna Krylov. Institutions and journals, they asserted, have forgotten “scientific merit” and replaced it with ideology, fearing that the so-called “wokists” are supported by governments and official agencies in the same way that Trofim Lysenko’s false theory of the inheritance of acquired characters was enforced by Stalin. If true, this is terrible news, since in USSR the ideological supremacy of Lysenkoism led to many executions and exiles.

Russian Federation foundation/Wikimedia, CC BY

The “anti-wokeist” have raised analogous critiques on many occasions. An example in the humanities was the denouncement of the disclosure of the relations between poet Ted Hughes’s family and slavery. In psychology, there was the case where the introduction of the notion of “white privilege” in psychology was criticized.

The tricky concept of scientific merit

Coyne and Krylov speak of biology, but one would easily admit that the controversies over so-called wokism, social justice and truth are a concern for academia overall, which includes natural sciences, social sciences, humanities and law. Their claim is supposed to hold for academia in general, and “scientific merit” is here synonymous with “academic merit”. (These two terms will be used equivalently hereafter.) But such notion of “scientific merit” is obscure, and in the absence of a reliable method to measure it, invoking it is an empty claim. Worse, the way merit itself is used by institutions and policies proves ultimately much more deleterious to science than any radicalized “social-justice warrior ideology”, if this phrase is even meaningful.

“Merit” in academia means that one should be credited with a robust and measurable contribution to science. Yet when a discovery is made or some theorem is proved, this is always based on former works, as it has been reminded us through an exhaustive reconstitution of the role Rosalind Franklin played in the worldly praised discovery of DNA (1953) by Crick and Watson, who were awarded the Nobel Prize for this while Franklin died four years earlier. Hence the attribution of merit is complicated by the inextricability of causal contributions, making the notion of “intellectual credit” complex, as is the very idea of an “author”, to whom this credit in principle is due. As in a soccer or handball team, parsing each player’s contributions to the goal the team scored is no trivial business.

Thus, social conventions have been invented to overcome this almost metaphysical underdetermination of the “author” (and hence her or his merit). In science, one of them is the disciplines: being an author is not the same in mathematics as in sociology, and disciplines determine what is required to sign a paper, hence to be an author within a given field. Another conventional tool is the citation – the more one is cited, the higher their merit.

Citation rankings are therefore supposed to track the genuine grandeur of individuals. Estimating this requires listing all papers signed by an individual and cited by their peers, and gives rise to metrics such as the impact factor (for journals) or the h-index (for scientists), which are the basis of our merit system in science, since any assessment of one’s academic and chances to be hired, promoted or funded in any country juggles with such combined figures. As Canadian sociologist Yves Gingras put it, while the “paper” had been a unit of knowledge for four centuries, it is now also a unit of evaluation and is used daily by hiring committees and funding agencies worldwide.

Unlike what Coyne and Krylov say, these intend to find the most meriting scientists by tracking the number of citations and publications – the latter allowing one to increase the former, since the more papers you publish, the more citations your work will get. Hearing that China is now the first publishing country and worrying about its imminent victory in the race for publications, as we daily hear it, only makes sense if you equate science’s value with these grandeur metrics.

Where science loses out in the idea of merit

Yet measuring scientific merit in this way damages the quality of science for three reasons that have been analysed by scientists themselves. The overall result is that such kind of measurement yields “natural selection from bad science”, as the evolutionary biologists Paul E. Smaldino and Richard McElreath put it in a 2016 paper. Why?

First, one can easily game the metrics – for example, by slicing one paper into two, or writing one more paper by solely tweaking the parameters of a model. Obviously, this strategy unnecessarily expands the amount of literature that researchers have to read and thereby increases the difficulty of distinguishing signal from noise in a growing forest of academic papers. Shortcuts such as fraud or plagiarism are also thereby incentivized; no wonder that agencies for scientific integrity and trackers of scientific misconduct have proliferated.

Second, this measure of merit induces less exploratory science, since being exploratory takes time and risks finding nothing so that your competitors will reap all the rewards. For the same reason, journals will favour what ecologists traditionally refer to as exploitation rather than exploration of new territories, since their impact factor relies on citation numbers. A recent Nature paper argued that science became much less disruptive in the last decade, while bibliometry-based assessments have flourished.

Finally, even if one wants to keep a measure of merit related to publication activity, bibliometry-based merit is unidimensional because real science – as revealed by its computer-assisted quantitative study – develops as an unfolding landscape rather than a linear progress. Therein, what constitutes a “major contribution” to science could take several forms, depending on where one stands in this landscape.

Rethinking scientific progress

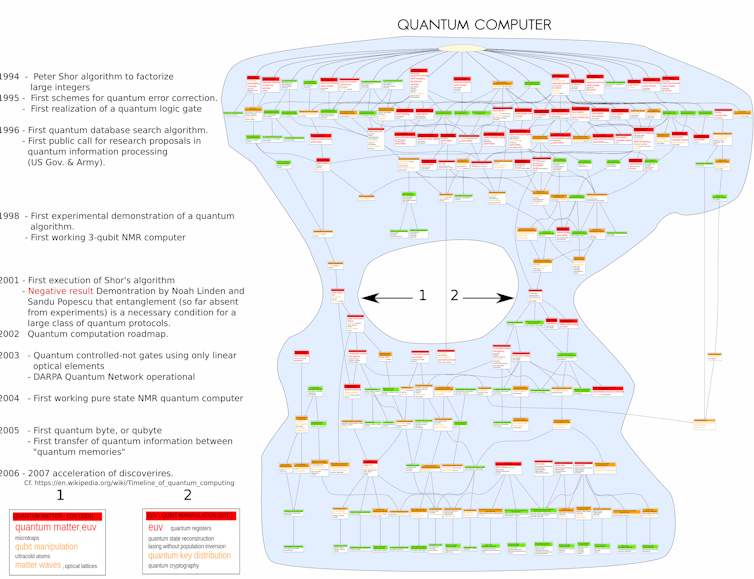

At the ISC-PIF (Paris) researchers have mapped the dynamics of science by detecting over the years the emergence, fusion, fission, and divergence of topics defined by clusters of correlated words (as exemplified in the figure below about the field of quantum computing, where fissions and merging that occurred in the history of the field are graphically visible). It appears that the kinds of work done by scientists in distinct stages of arising, growth, or decline of a field (understood here as a set of topics) are very different, and yield incomparable types of merits.

Author provided

When a field is mature, it is easy to produce many papers. However, when it is emerging – for instance by the fission of a field or the fusion of two previous ones – the publications and audiences are scarce, so that one cannot produce as many papers as a competitor working in a more mature field. Levelling everything through common reference to citation numbers – notwithstanding how refined might be the metrics – will always miss the proper nature of each specific contribution to science.

Whatever the word merit means in science, it is multidimensional, thus all bibliometry-based indexes and metrics will miss it because they will turn it into a unidimensional figure. But this ill-defined and ill-measured merit, as the basis of any assessment of scientists and therefore allocation of resources (positions, grants, etc.), will be instrumental in shaping the physiognomy of academia and thereby corrupt science in a firmer way than any ideology.

Therefore, vindicating merit as it is currently assessed is not a gold standard for science. In turn, such merit is already known to be a deleterious approach to knowledge production, yielding several negative consequences for science as well as for scientists.