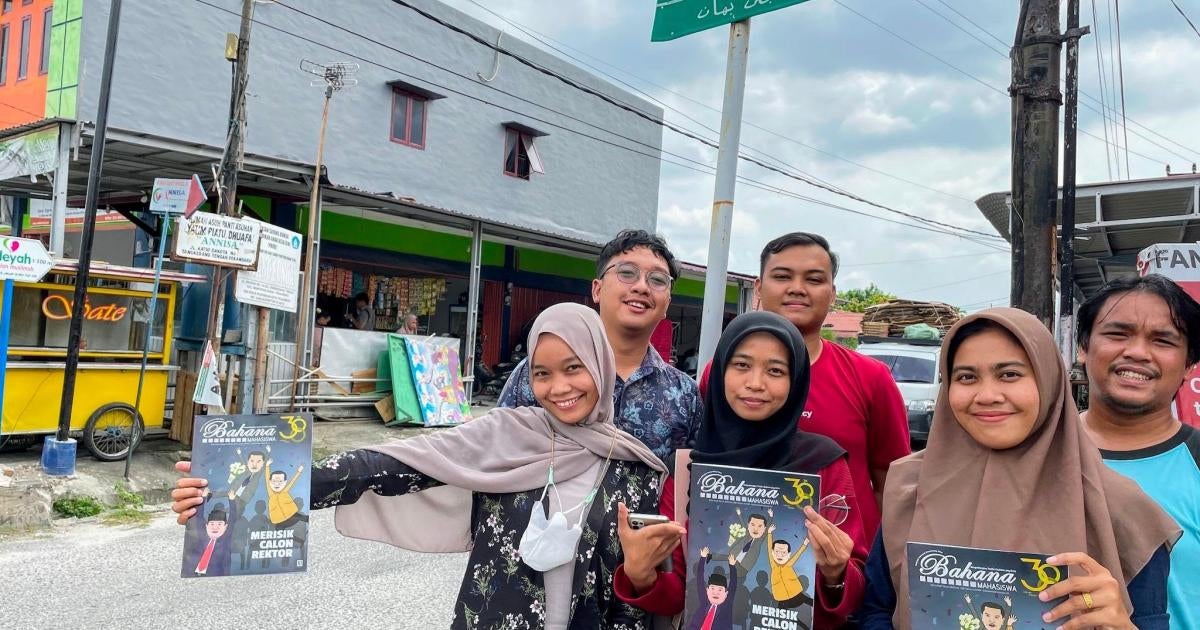

(Jakarta) – The Indonesian government should support the national Press Council’s efforts to protect university media outlets and mediate their disputes with school authorities, Human Rights Watch said today. On May 22, 2023, more than 150 college journalists will begin a week-long conference in Solo, Central Java, to discuss intimidation, attacks, and forced closures of university media, and the need for government action.

“Student journalists in Indonesia face abuses ranging from intimidation and censorship to defamation charges and newsroom shutdowns, and they have been left defenseless in this onslaught against press freedom,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The government and Press Council need to expose this media crisis and act to protect and support these student journalists.”

Between 2020 and 2021, the Indonesian Student Press Association (Perhimpunan Pers Mahasiswa Indonesia) recorded 48 cases of university administrators intimidating or shutting down student media outlets among the 185 cases of alleged press-related abuses on campuses in the country. The abuses included threats, intimidation, physical assault, closure of media outlets, and expulsion of students because of their journalism work.

Most Indonesian universities have at least one student media outlet, such as a newspaper, magazine, or online news site, and many of the older universities have several. While some of the older student press organizations produce printed publications, including some that have been published continually since the 1960s, both older and newer outlets publish their content on internet websites and use social media.

The 1999 Press Law, which set up the Press Council to mediate defamation disputes, defines a press organization as media that has an independent legal status like a limited corporation, a foundation, or a cooperative. However, student media operates under the official purview of their educational institution, and by extension, the Ministry of Education for non-Islamic schools and the Ministry of Religious Affairs for Islamic schools. For this reason, the Press Council systems don’t protect student media outlets.

While student media organizations operate within the structure of their universities, many student media outlets operate like traditional independent newsrooms. This has often brought these organizations into conflict with the university administration when student reporters uncover and report on malfeasance, corruption, sexual misconduct, and other sensitive issues at their university.

Under a 2017 memorandum of understanding between the Press Council and the National Police, any report of alleged defamation involving the media should be referred to the Press Council. The National Police agreed that they would only process a defamation case against the media if the complainant had already reported the case to the Press Council. Such Press Council mediation has played an important role in resolving such complaints and protecting freedom of the press.

However, criminal defamation cases involving student journalists and publications are directly handled by the local police station, where officers are more easily swayed by influential local elites pressing cases against student publications.

The national Press Council in Jakarta should engage with national police, the Education Ministry, and the Religious Affairs Ministry, and seek an agreement that would direct all college media disputes to be mediated by the Press Council, Human Rights Watch said.

In March 2019, the North Sumatra University in Medan shut down the Suara USU newsroom after a lesbian love story went viral, ordering the 18 student journalists linked to the news website to vacate the newsroom within 48 hours. The students filed a lawsuit against the university in July 2019 but lost at the Medan administrative court in November 2019. In January 2020, they set up Wacana news website, operating outside the campus structure, and thus without financial support.

In March 2022, the Ambon Islamic State Institute closed the Lintas student magazine, ordering campus security to seal the newsroom and seize all equipment, after accusing its reporters and editors of “defaming” the campus. The story that angered the administration documented a highly disturbing atmosphere of impunity for sexual assault of students on campus, and the university leadership’s failure to address it. Five men who said they were relatives of an implicated lecturer assaulted two student journalists. Abidin Rahawarin, the university’s rector, reported nine other student journalists to the police for criminal defamation.

Lintas had spent five years investigating accounts of sexual assault on campus and had interviewed 32 survivors (27 female and 5 male students). After mediation, the university rector agreed to not press the criminal defamation complaint but replaced all the Lintas staff with other students.

Research by the Indonesian Student Press Association found that the most common actions against student media outlets are intimidation and threats by university leaders, administrators, and other powerful people on their campuses. The most frequent demand was for post-publication censorship, usually to remove certain news stories from the student news websites. Even university lecturers have been involved, as in August 2021, when Anhar Anshori, the head of university book publications, demanded that the Poros student news site at the Ahmad Dahlan University in Yogyakarta remove a story about another lecturer selling a book he wrote on campus.

Student journalism has a long history in Indonesia. Several of Indonesia’s founders, including Mohammad Hatta and Sutan Sjahrir, respectively Indonesia’s first vice president and prime minister in the 1940s, were student journalists in the Netherlands in the 1920s. The student press association has at least 400 members from various college media organizations on the major Indonesian islands of Bali, Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi. Some other islands also have their own associations, as do several cities.

“The Indonesian government should provide a meaningful response to student media leaders for the serious issues they have identified,” Robertson said. “Key government agencies and the Press Council should set up a task force to devise and put in place an agreement to protect student journalists and their publications.”