As many countries grapple with ageing populations, falling birthrates, labour shortages and fiscal pressures, the ability to successfully integrate immigrants is becoming an increasingly pressing matter.

However, our new study found that salaries of immigrants in Europe and North America are nearly 18% lower than those of natives, as foreign-born workers struggle to access higher-paying jobs. To reach this conclusion, we analysed the salaries of 13.5 million people in nine immigrant-receiving countries: Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the United States. Data was taken from the period of 2016 to 2019.

Immigrants in these countries earned less primarily because they were unable to access higher-paying jobs. Three-quarters of the migrant pay gap was the result of a lack of access to well-paid jobs, while only one-quarter of the gap was attributed to pay differences between migrant and native-born workers in the same job.

Author’s own elaboration

The high-income countries we examined in Europe and North America all face similar demographic challenges, with low fertility rates resulting in an ageing population and labour shortages. Pro-natalist policies are unlikely to change this demographic destiny, but sound immigration policies can help.

Across these countries with vastly different labour market institutions and immigrant populations, a common theme emerged: countries are not making good use of immigrants’ human capital.

Stark regional differences

We found that immigrants earn 17.9% less than natives on average, although the pay gap varied widely by country. In Spain, a relatively recent large-scale receiver of immigrants, the pay gap was over 29%. In Sweden – a country where many employed immigrants find work in the public sector – it was just 7%. These results don’t include immigrants who are unemployed or in the informal economy.

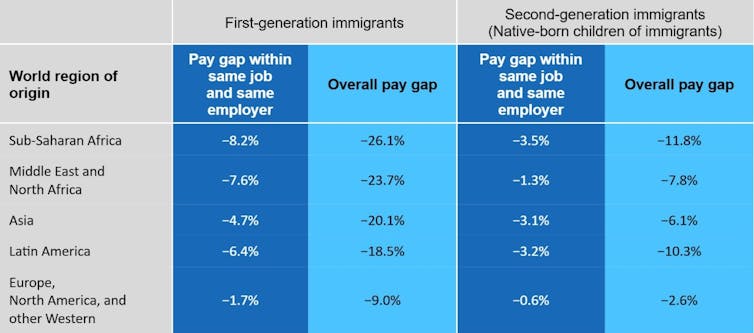

Where immigrants were born also mattered. The highest average overall pay gaps were for immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa (26.1%) and the Middle East and North Africa (23.7%). For immigrants from Europe, North America and other Western countries, the difference in average pay compared to natives was a much more modest 9%.

Author’s own elaboration

Our results suggest that the children of immigrants faced substantially better earning prospects than their parents. For the countries where second-generation data was available – Canada, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden – the gap narrowed over time, and the children of immigrants had a substantially smaller earnings gap, earning an average of 5.7% less than workers with native-born parents.

The struggle to access higher-paying jobs

Beyond quantifying the gap, we wanted to understand the roots of pay disparities. To create better policies, it is important to know whether immigrants are paid less than natives when they’re doing the same job in the same company, or whether these differences arise because immigrants typically work in lower-paying jobs.

By a wide margin, we found that immigrants end up working in lower-paying industries, occupations and companies; three-quarters of the gap was due to this type of labour-market sorting. The pay gap for the same work in the same company was just 4.6% on average across the nine countries.

These differences represent a failure of immigration policy to incorporate immigrants, as immigrants are relegated to jobs where they cannot contribute to their full potential. Our analyses rule out that the lack of access to higher-paying jobs simply reflects a difference in skill between immigrants and native-born workers. We also found that the size of the pay gap and the key role of unequal access to well-paid jobs is similar for immigrants with and without a university education.

This means that the immigrant-native pay gap in large part represents a market inefficiency and policy failure, with significant social consequences for both immigrants and immigrant-receiving countries.

Read more:

What Britons and Europeans really think about immigration – new analysis

Policy implications

Although equal pay for equal work policies may seem like a viable solution, they won’t close the immigrant pay gap. This is because they only help those who have already secured work, but immigrants face barriers to employment that begin long before even applying for a job. This includes convoluted processes to validate university degrees or other qualifications, and exclusion from professional networks.

The policy focus should therefore be on improving access to better jobs.

To make this happen, governments should invest in programmes such as language training, education and vocational skills for immigrants. They should ensure immigrants have early access to employment information, networks, job-search assistance and employer referrals. They should implement standardised and transparent recognition of foreign degrees and credentials, helping immigrants to access jobs matching their skills and training.

This is particularly important for Europe as it races to attract – and retain – skilled immigrants who may be having second thoughts about the US in the Trump era. In the European Union, around 40% of university-educated non-EU immigrants are employed in jobs that do not require a degree, an underutilisation of skills known as brain waste.

Some countries are already taking steps to remedy this. Germany’s Skilled Immigration Act – which took effect in 2024 – allows foreign graduates to work while their degrees are being formally recognised. In 2025, France reformed its Passeport Talent permit to attract skilled professionals and address labour shortages, especially in healthcare.

These kinds of policies help ensure that foreign-born workers can contribute at their full capacity, and that countries can reap the full benefits of immigration in terms of productivity gains, higher tax revenue and reduced inequality.

If immigrants can’t get access to good jobs, their skills are underutilised and society loses out. Smart immigration policy doesn’t end at the border – it starts there.