When she took to the floor to give her State of the Union speech on 13 September, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen largely stood by the script. Describing her vision of an economically buoyant and sustainable Europe in the era of climate change, she called on the EU to accelerate the development of the clean-tech sector, “from wind to steel, from batteries to electric vehicles”. “When it comes to the European Green Deal, we stick to our growth strategy,” von der Leyen said.

Her plans were hardly idiosyncratic. The notion of green growth – the idea that environmental goals can be aligned with continued economic growth – is still the common economic orthodoxy for major institutions like the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The OECD has promised to “strengthen their efforts to pursue green growth strategies […], acknowledging that green and growth can go hand-in-hand”, while the World Bank has called for “inclusive green growth” where “greening growth is necessary, efficient, and affordable”. Meanwhile, the EU has framed green growth as

“a basis to sustain employment levels and secure the resources needed to increase public welfare […] transforming production and consumption in ways that reconcile increasing GDP with environmental limits”.

However, a survey of nearly 800 climate policy researchers from around the world reveals widespread scepticism toward the concept in high-income countries, amid mounting literature arguing that the principle may neither be viable nor desirable. Instead, alternative post-growth paradigms including “degrowth” and “agrowth” are gaining traction.

Frederick Florin/AFP

Differentiating green growth from agrowth and degrowth

But what do these terms signify?

The “degrowth” school of thought proposes a planned reduction in material consumption in affluent nations to achieve more sustainable and equitable societies. Meanwhile, supporters of “agrowth” adopt a neutral view of economic growth, focusing on achieving sustainability irrespective of GDP fluctuations. Essentially, both positions represent scepticism toward the predominant “green growth” paradigm with degrowth representing a more critical view.

Much of the debate centres around the concept of decoupling – whether the economy can grow without corresponding increases in environmental degradation or greenhouse gas emissions. Essentially, it signifies a separation of the historical linkage between GDP growth and its adverse environmental effects. Importantly, absolute decoupling rather than relative decoupling is necessary for green growth to succeed. In other words, emissions should decrease during economic growth, and not just grow more slowly.

Green growth proponents assert that absolute decoupling is achievable in the long term, although there is a division regarding whether there will be a short-term hit to economic growth. The degrowth perspective is critical that absolute decoupling is feasible at the global scale and can be achieved at the rapid rate required to stay within Paris climate targets. A recent study found that current rates of decoupling in high-income are falling far short of what is needed to limit global heating to well below 2°C as set out by the Paris Agreement.

The agrowth position covers more mixed, middle-ground views on the decoupling debate. Some argue that decoupling is potentially plausible under the right policies, however, the focus should be on policies rather than targets as this is confusing means and ends. Others may argue that the debate is largely irrelevant as GDP is a poor indicator of societal progress – a “GDP paradox” exists, where the indicator continues to be dominant in economics and politics despite its widely recognised failings.

7 out of 10 climate experts sceptical of green growth

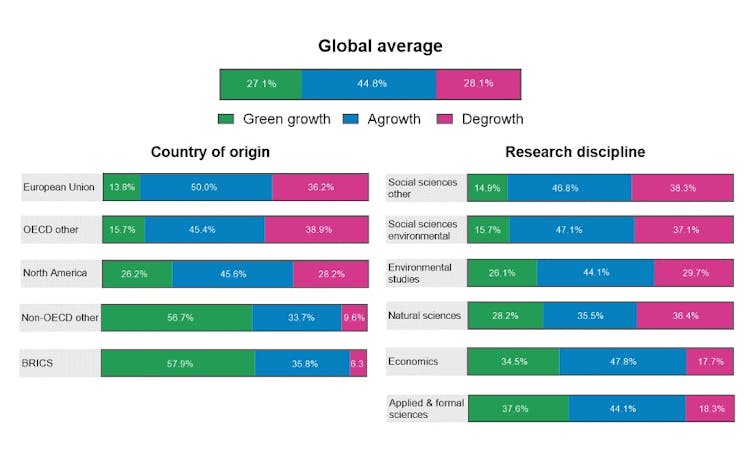

How prevalent are degrowth and agrowth views among experts? As part of a recent survey completed by 789 global researchers who have published on climate change mitigation policies, we asked questions to assess the respondents’ positions on the growth debate. Strikingly, 73% of all respondents expressed views aligned with “agrowth” or “degrowth” positions, with the former being the most popular. We found that the opinions varied based on the respondent’s country and discipline (see the figure below).

Fourni par l’auteur

While the OECD itself strongly advocates for green growth, researchers from the EU and other OECD nations demonstrated high levels of scepticism. In contrast, over half of the researchers from non-OECD nations, especially in emerging economies like the BRICS nations, were more supportive of green growth.

Disciplinary rifts

Furthermore, a disciplinary divide exists. Environmental and other social scientists, excluding orthodox economists, were the most sceptical of green growth. In contrast, economists and engineers showed the highest preference for green growth, possibly indicative of trust in technological progress and conventional economic models that suggest economic growth and climate goals are compatible.

Our analysis also examined the link between the growth positions and the GDP per capita of a respondent’s country of origin. A discernible trend emerged: as national income rises, there is increased scepticism toward green growth. At higher income levels, experts increasingly supported the post-growth argument that beyond a point, the socio-environmental costs of growth may outweigh the benefits.

The results were even more pronounced when we factored in the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI), suggesting that aspects beyond income, such as inequality and overall development, might influence these views.

In a world grappling with climate change and socio-economic disparities, these findings should not simply be dismissed. They underline the need for a more holistic dialogue on sustainable development, extending beyond the conventional green growth paradigm.

Post-growth thought no longer a fringe position

Although von der Leyen firmly stood in the green growth camp, this academic shift is increasingly reflected in the political debate. In May 2023, the European Parliament hosted a conference on the topic of “Beyond Growth” as an initiative of 20 MEPs from five different political groups and supported by over 50 partner organisations. Its main objective was to discuss policy proposals to move beyond the approach of national GDP growth being the primary measure of success.

Six national and regional governments – Scotland, New Zealand, Iceland, Wales, Finland, and Canada – have joined the Wellbeing Economy Governments (WEGo) partnership. The primary aim of the movement is to transition to “an economy designed to serve people and planet, not the other way around.”

Clearly, post-growth thought is no longer a fringe, radical position within those working on solutions to climate change. Greater attention needs to be given to why some experts are doubtful that green growth can be achieved as well as potential alternatives focussed on wider concepts of societal wellbeing rather than limited thinking in terms of GDP growth.